Operation Crimson Palace: Sophos threat hunting unveils multiple clusters of Chinese state-sponsored activity targeting Southeast Asian government

Credit to Author: gallagherseanm| Date: Wed, 05 Jun 2024 10:00:34 +0000

In May 2023, in a threat hunt across Sophos Managed Detection and Response telemetry, Sophos MDR’s Mark Parsons uncovered a complex, long-running Chinese state-sponsored cyberespionage operation we have dubbed “Crimson Palace” targeting a high-profile government organization in Southeast Asia.

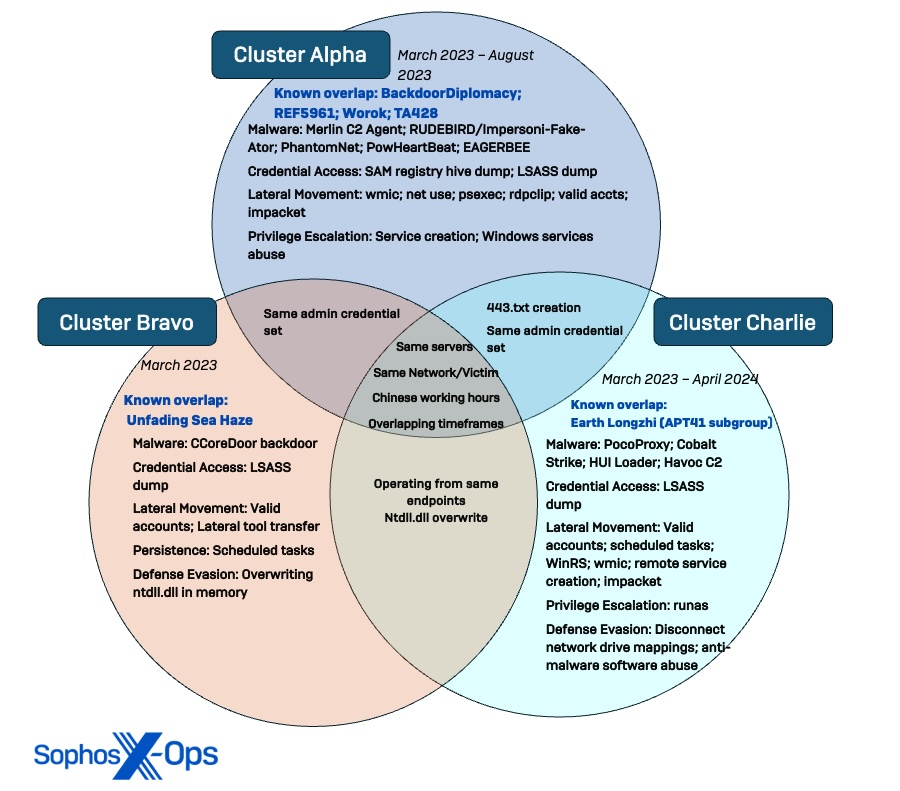

MDR launched the hunt after the discovery of a DLL sideloading technique that exploited VMNat.exe, a VMware component. In the investigation that followed, we tracked at least three clusters of intrusion activity from March 2023 to December 2023. The hunt also uncovered previously unreported malware associated with the threat clusters, as well as a new, improved variant of the previously-reported EAGERBEE malware. In line with our standard internal nomenclature, Sophos tracks these clusters as Cluster Alpha (STAC1248), Cluster Bravo (STAC1807), and Cluster Charlie (STAC1305).

While our visibility into the targeted network was limited due to the extent to which Sophos endpoint protection had been deployed within the organization, our investigations also found evidence of related earlier intrusion activity dating back to early 2022. This led us to suspect the threat actors had long-standing access to unmanaged assets within the network.

The clusters were observed using tools and infrastructure that overlap with other researchers’ public reporting on Chinese threat actors BackdoorDiplomacy, REF5961, Worok, TA428, the recently-designated Unfading Sea Haze and the APT41 subgroup Earth Longzhi. Additionally, Sophos MDR has observed the actors attempting to collect documents with file names that indicate they are of intelligence value, including military documents related to strategies in the South China Sea.

Based on our investigation, Sophos asserts with high confidence the overall goal behind the campaign was to maintain access to the target network for cyberespionage in support of Chinese state interests. This includes accessing critical IT systems, performing reconnaissance of specific users, collecting sensitive military and technical information, and deploying various malware implants for command-and control (C2) communications. We have moderate confidence that these activity clusters were part of a coordinated campaign under the direction of a single organization. Sophos is sharing indicators and context for the Crimson Palace campaign in hopes of contributing to further public research and helping other defenders and analysts disrupt related activity.

Sophos has repeatedly shared the details of the intrusion with authorized contacts for the targeted organization. Sophos MDR continues to closely monitor this environment to report the scope and scale of the ongoing activity to the victim organization, as well as collect intelligence to track attack tactics and generate updated detections for all Sophos customers. Sophos has also shared intelligence from this campaign with government and industry partners, including Elastic Security and Trend Micro who have previously reported on similar threats.

Key findings of our investigation included:

- Novel malware variants: Sophos identified the use of previously unreported malware we call CCoreDoor (concurrently discovered by BitDefender) and PocoProxy, as well as an updated variant of EAGERBEE malware with new capabilities to blackhole communications to anti-virus (AV) vendor domains in the targeted organization’s network. Other observed malware variants include NUPAKAGE, Merlin C2 Agent, Cobalt Strike, PhantomNet backdoor, RUDEBIRD malware, and the PowHeartBeat backdoor.

- Extensive dynamic link library (DLL) sideloading abusing Windows and anti-virus binaries: The Crimson Palace campaign included over 15 distinct DLL sideloading scenarios, most of which abused Windows Services, legitimate Microsoft binaries, and AV vendor software.

- High prioritization of evasive tactics and tools: The threat actors leveraged many novel evasion techniques, such as overwriting dll in memory to unhook the Sophos AV agent process from the kernel, abusing AV software for sideloading, and using various techniques to test the most efficient and evasive methods of executing their payloads.

- Three distinct clusters with overlaps indicating coordination: While Sophos identified three distinct patterns of behavior, the timing of operations and overlaps in compromised infrastructure and objectives suggest at least some level of awareness and/or coordination between the clusters in the environment.

Because of the amount of intelligence uncovered in our investigation into this campaign, we have divided our report in two. This article provides an overview of the campaign and highlights the overlap of the observed activity clusters and the malware unique to them. Full technical analysis of the activity clusters is provided in a technical appendix, also published today. We have provided links from within this article to relevant portions of the detailed analysis in that article.

Prior Compromise

The targeted organization is categorized by Sophos as a “mixed estate,” meaning Sophos Managed Detection and Response (MDR) and Extended Detection and Response (XDR) coverage are only deployed to a subset of endpoints. Because of this, the Sophos team lacks complete visibility over all assets in the environment, leading us to assess the full extent of the compromise likely extends beyond Sophos-protected endpoints and servers.

While initial access occurred outside Sophos’ visibility into the organization, we observed related activity dating back to early 2022. That included a March 2022 detection of NUPAKAGE malware (Troj/Steal-BLP), a customized tool used for exfiltration that has been publicly attributed by Trend Micro to the Chinese threat group Earth Preta (aka Mustang Panda).

The organization later enrolled a subset of their endpoints with Sophos’ MDR service. Detections of suspicious activity prompted the MDR Operations team to investigate the organization’s estate. This included a December 2022 investigation into intrusion activity where DLL-stitching was used to obfuscate and deploy two malicious backdoors on target domain controllers. At that time, the detections Troj/Backdr-NX and ATK/Stowaway-C were deployed across Sophos customers to detect the stitched DLL payloads, and a behavioral detection was created to detect when a service DLL is added to the Windows registry.

A deeper analysis of these previous compromises can be found here.

Analysis of Activity Clusters

The threat hunt that identified the activity clusters covered in this report began in May 2023. During the investigation, Sophos analysts identified several patterns indicating distinct clusters of behavior were operating in the network during the same period. These included:

- Authentication data, including source subnet, workstation hostname, and account usage

- Techniques, including specific commands and options, repeatedly used by the attackers

- Attacker C2 infrastructure

- Unique tools and the paths where they were deployed

- Targeted user accounts and hosts

- Timing of the observed activity

Based on these patterns, we assess with moderate confidence that the espionage campaign consisted of at least three activity clusters with separate sets of infrastructure and TTPs coexisting in the target organization’s network from at least March to September 2023.

For more information on the attack chains of the observed clusters and details on the novel tactics and tooling, refer to the attack chain details report.

Cluster Alpha (STAC1248)

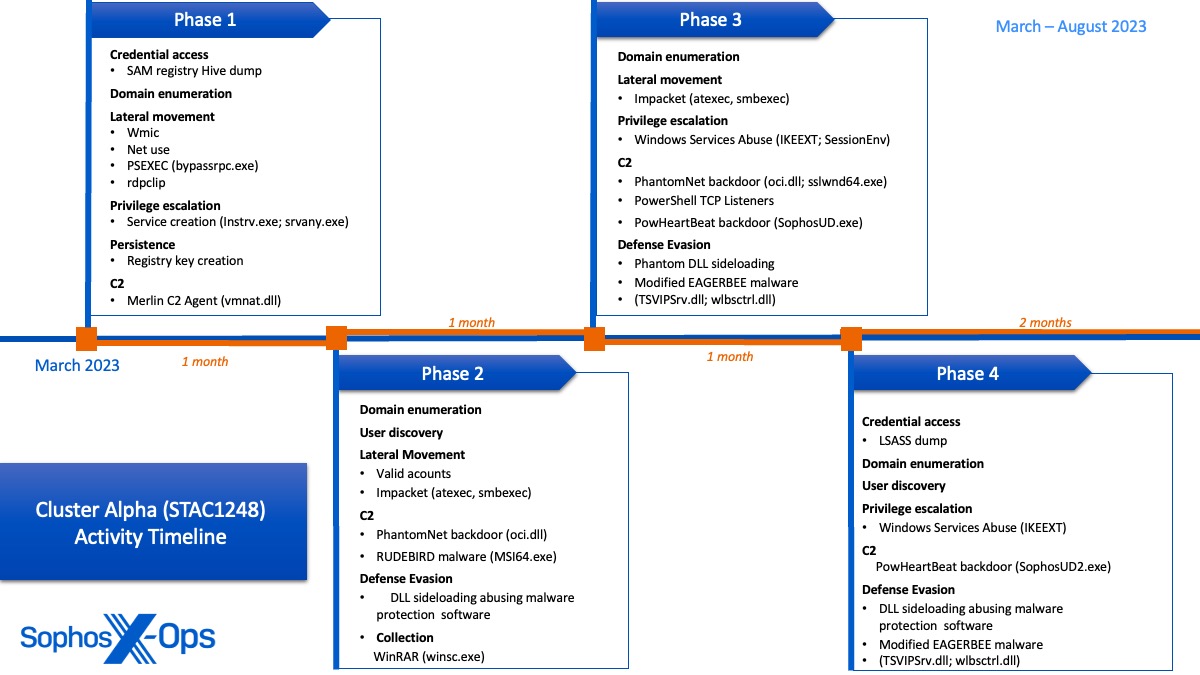

We observed Cluster Alpha activity from early March to at least August 2023. That activity included multiple sideloading attempts to deploy various malware and establish persistent C2 channels within client and server subnets. Throughout this activity, we observed mutations of successful tactics that resulted in the same outcome, indicating the threat actors may have been leveraging the victim network as a playground to test different techniques. In addition to using unique techniques to disable AV protections and escalate privileges, the actor operating in Cluster Alpha prioritized comprehensively mapping server subnets, enumerating administrator accounts, and conducting reconnaissance on Active Directory infrastructure.

Key observations

- Deployment of new EAGERBEE malware variants with updated capability of modifying packets to disrupt security agent network communications

- Use of multiple persistent C2 channels including Merlin Agent, PhantomNet backdoor, RUDEBIRD malware, EAGERBEE malware, and PowHeartBeat backdoor

- Leverage of uncommon LOLBins exe and srvany.exe for service persistence with elevated SYSTEM privileges

- Side-loading of eight unique DLLs abusing Windows Services, legitimate Microsoft binaries, and endpoint protection vendors’ software

A further analysis of Cluster Alpha can be found here.

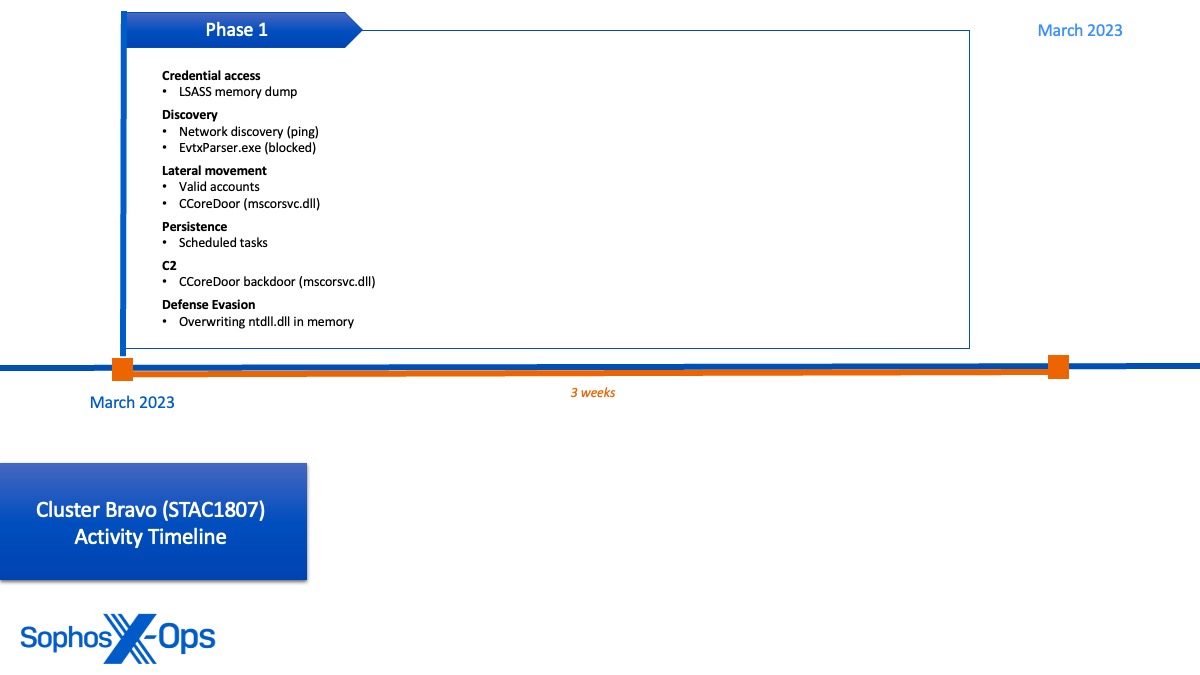

Cluster Bravo (STAC1807)

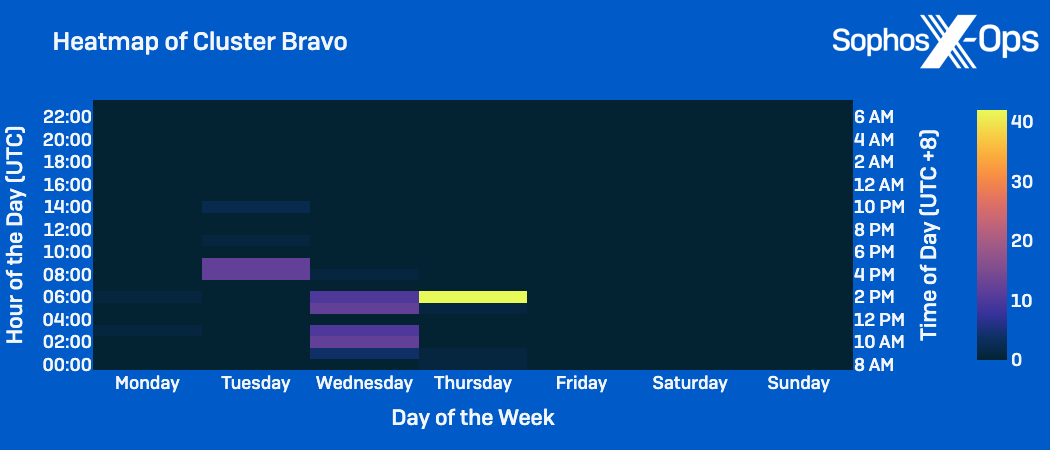

While the activity in the other two clusters spanned over several months, activity in Cluster Bravo was only observed in the targeted organization’s environment for a three-week span in March 2023 (coinciding with the first session of China’s 14th National People’s Congress). Characterized as a mini cluster because of its short duration, Cluster Bravo activity was primarily focused on using valid accounts to spread laterally throughout the network, with the goal of sideloading a novel backdoor to establish C2 communications and maintain persistence on target servers.

Key observed behavior included:

- Deployment of a previously unreported backdoor (which we have dubbed CCoreDoor) to move laterally, establish external C2 communications, perform discovery, and dump credentials

- Use of renamed versions of a signed side-loadable binary (exe) to obfuscate backdoor deployment and move laterally from the beachhead host to other remote servers

- Connections made to other hosts that were verified to be running within other in-country government organizations who may also be potentially compromised

- Overwriting of ntdll.dll in memory with an on-disk version to unhook the Sophos endpoint protection agent process from the kernel

Further details on Cluster Bravo can be found here.

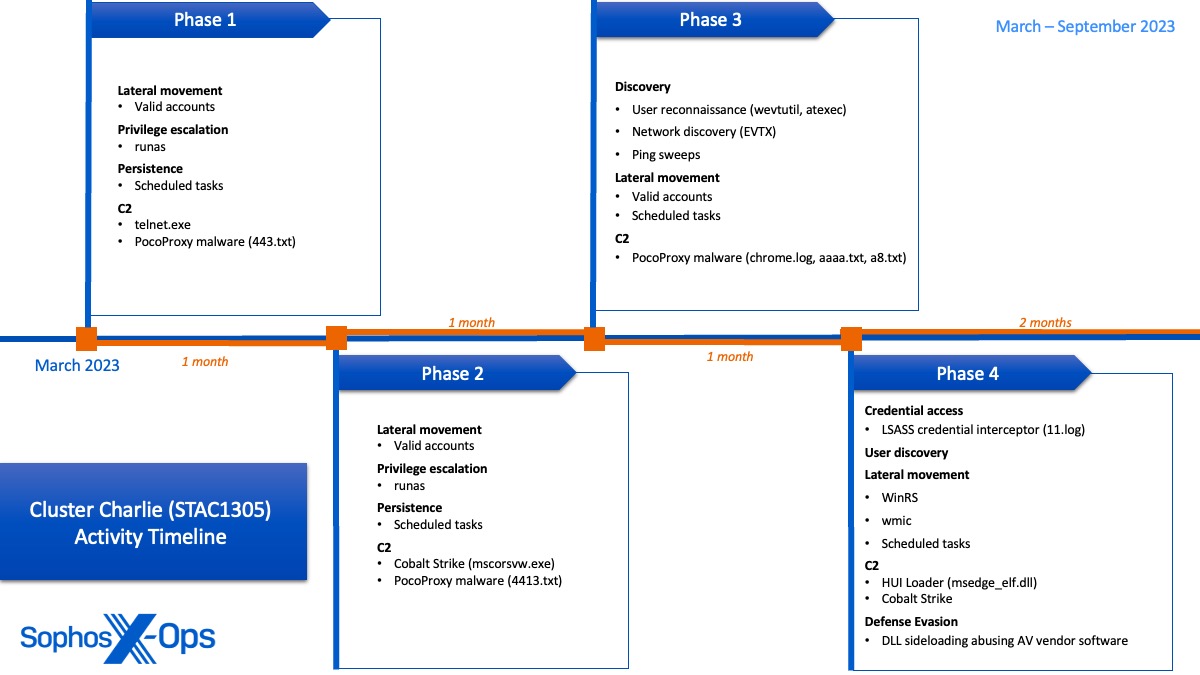

Cluster Charlie (STAC1305)

Sophos MDR hunters observed Cluster Charlie activity in the target network for the longest period, with operations spanning from March to at least April 2024. Appearing to highly prioritize access management, the actor deployed multiple implants of a previously unidentified malware, dubbed PocoProxy, to establish persistence on target systems and rotate to new external C2 infrastructure.

In a day in June 2023, activity in Cluster Charlie spiked as the actors conducted some of their noisiest discoveries, including mass analysis of Event Logs for environment-wide user and network reconnaissance. The output of this reconnaissance was used to conduct automated ping sweeps over the network, with the suspected goal of mapping all users and endpoints in the network. Notably, this day was a holiday in the target organization’s country, suggesting the threat actor was saving their most overt activity for a day with a lower expected response time. While discovery and lateral movement efforts continued over the next several months, Cluster Charlie activity was later observed attempting to exfiltrate sensitive information, which based on the file names involved and data collected, we assess with high confidence was for espionage purposes.

Key observed behavior included:

- Deployment of several samples of a previously unreported malware (which we call PocoProxy) for persistent C2 communications

- Collection and exfiltration of a large volume of data, including sensitive military and political documents, data on infrastructure architecture, and credentials/tokens for further in-depth access

- Deployment of a custom malware loader called HUI loader to inject a Cobalt Strike Beacon into mstsc.exe, which was blocked by Sophos HMPA protections

- Injection of an LSASS logon credential interceptor into exe to capture credentials on domain controllers

- Execution of wevtutil commands to conduct specific user reconnaissance, using the output to launch automated ping sweeps against thousands of targets across the network

Further details on Cluster Charlie can be found here.

Attribution and Cluster Overlap

Based on combined aspects of victimology, temporal analysis, infrastructure, tooling, and actions on objectives, we assess with high confidence the observed activity clusters are associated with Chinese state-sponsored operations.

In addition to the timing of activity in the clusters aligning with standard Chinese working hours, several observed TTPs overlap with industry reporting on Chinese-nexus actors. Furthermore, the target network is a high-profile government organization in a Southeast Asian country known to have repeated conflict with China over territory in the South China Sea. We assess the goal behind this campaign is long-term espionage, evidenced by the three clusters creating redundant C2 channels across the network to ensure persistent access and collect information related to Chinese state interests.

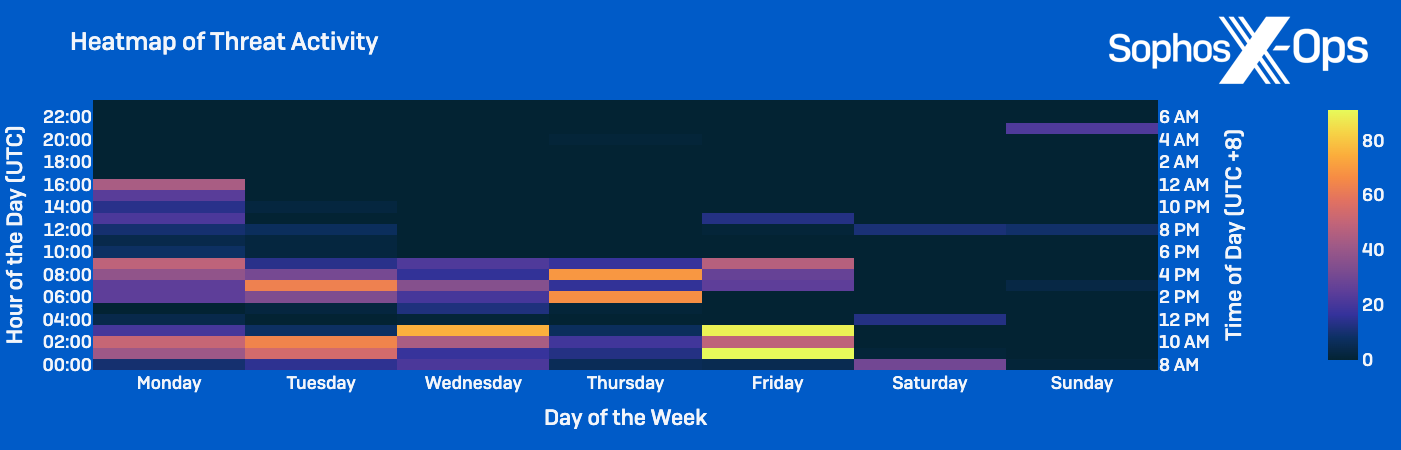

Consistent Chinese Operating Hours

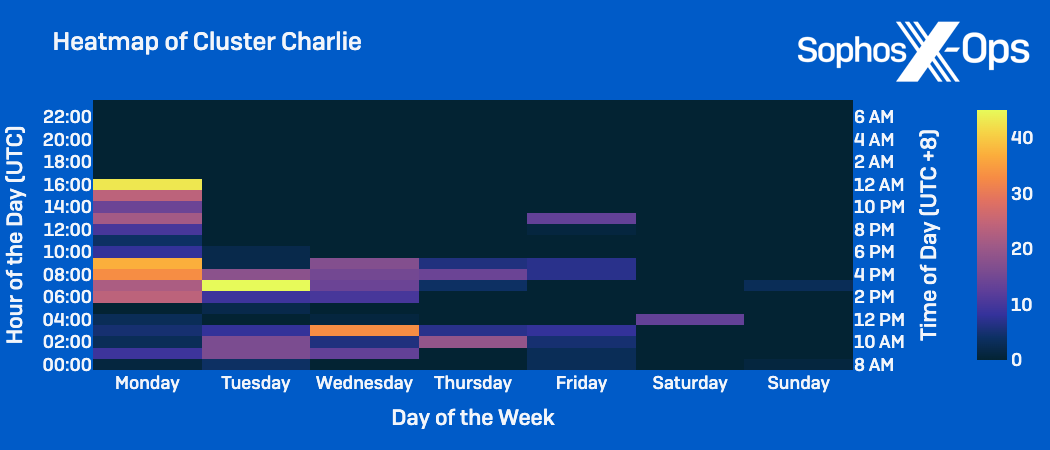

According to our analysis of activity frequency, activity in the clusters primarily occurred between 00:00 and 09:00 Coordinated Universal Time (UTC) Monday through Friday, equal to typical Chinese working hours of 8am to 5pm China Standard Time (CST).

Analyzing the Clusters’ Operating Schedules

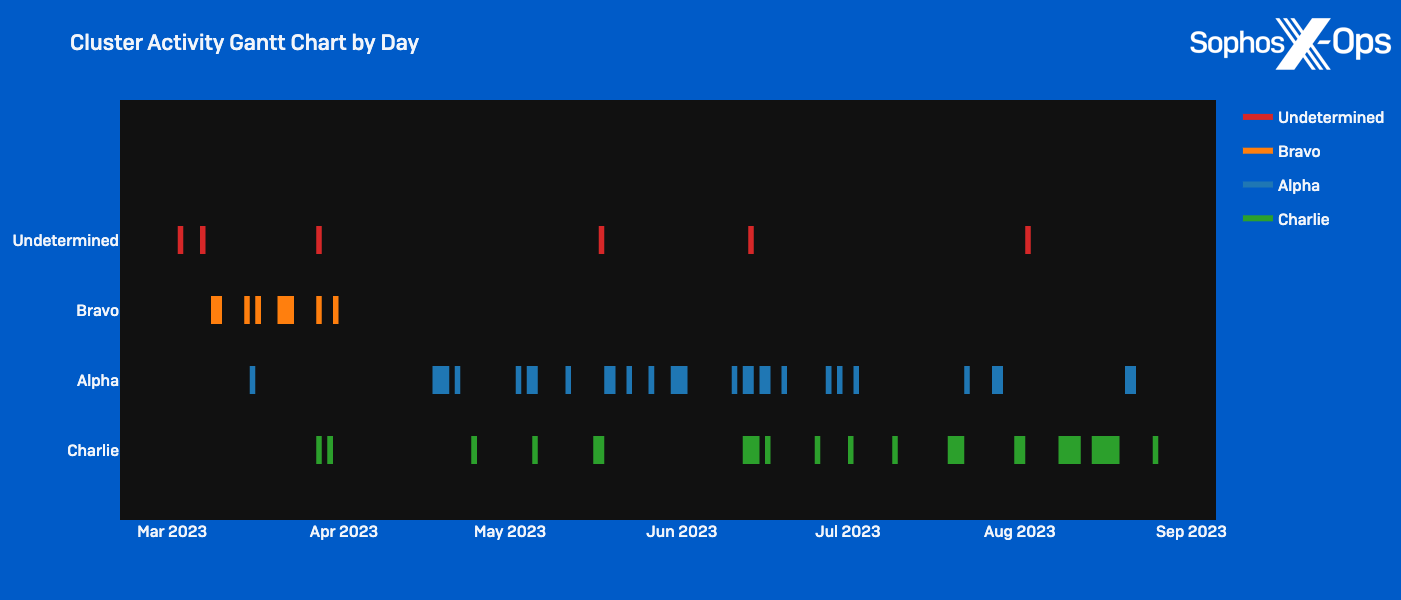

Temporal analysis of the individual activity clusters revealed distinct variations in the timing of their operations, where they were rarely observed performing extensive actions on the same day.

In fact, the clusters appear to schedule activity around one another, lending evidence the threat actors in the clusters may be aware of the others’ activities. At some points, Cluster Alpha and Cluster Charlie activity appeared to alternate by day, such as when activity in Cluster Alpha paused from June 10 to June 13 as Cluster Charlie’s spike of activity occurred on June 12.

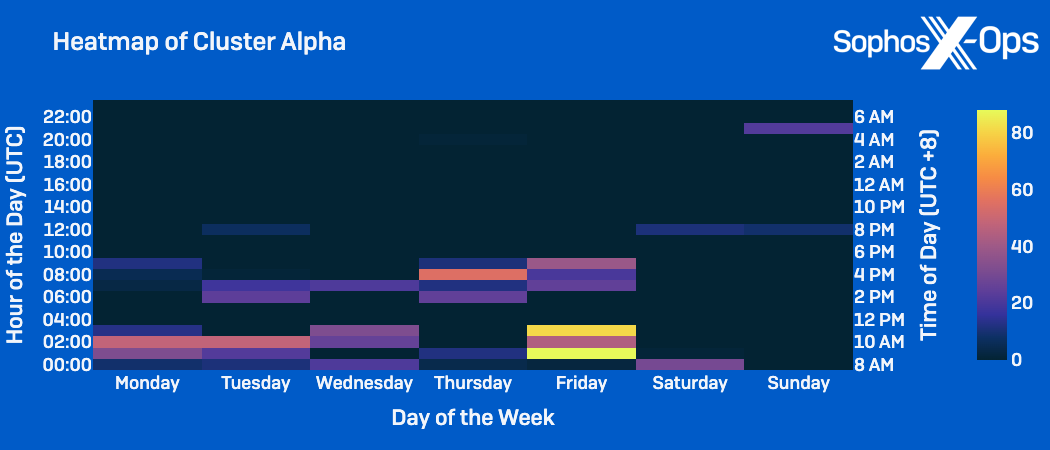

In analyzing the time and days of the week the clusters were most active, we noticed similar distinctions:

- Cluster Alpha activity: Often occurred on weekdays within the traditional working hours of 8am to 5pm CST; Peaked on Friday.

- Cluster Bravo activity: Occurred within traditional working hours of 8am to 5pm CST, but was concentrated on Tuesday, Wednesday, and Thursday.

- Cluster Charlie activity: Varied the most outside standard working hours; Activity peaked Monday through Wednesday 12pm to 6pm CST.

- The concentration of Cluster Charlie activity on Monday from 3pm to 12am CST aligns with the cluster’s spike of activity on June 12, 2023, which was a Monday and a holiday in the victim organization’s country.

Attributing Clustered Activity

While Sophos MDR asserts with high confidence the observed threat clusters are associated with Chinese state-sponsored activity, we are refraining from making attributions to known threat actor groups at this time. One reason is that Chinese threat groups are commonly known to share infrastructure and tooling, making attribution more challenging. We have, however, identified areas of overlap between our specific observations and third-party reporting to add context to the activity.

Cluster Alpha

REF5961 Similarities

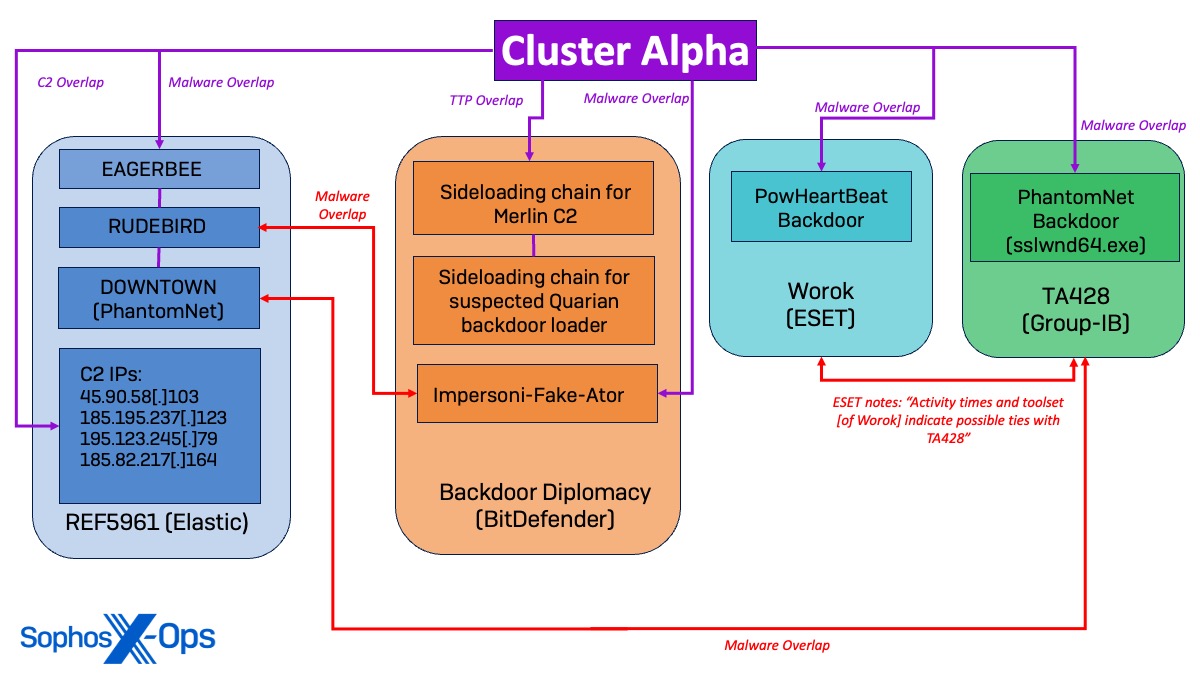

Three malware variants used in Cluster Alpha overlap with malware detailed in an October 2023 report by Elastic Security Labs on a Chinese-nexus actor tracked as REF5961. In the article, Elastic details REF5961’s use of EAGERBEE, RUDEBIRD, and DOWNTOWN (PhantomNet) malware to target the Foreign Affairs Ministry of an Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) member. Additionally, malware deployed in Cluster Alpha was observed connecting to several C2 IP addresses linked to REF5961.

BackdoorDiplomacy Similarities

Cluster Alpha activity also aligns with a case study by BitDefender on a cyberespionage campaign in the Middle East by a Chinese threat actor tracked as BackdoorDiplomacy, which is noted to overlap with other reported threat groups such as APT15, Playful Taurus, Vixen Panda, NICKEL, and Ke3chang.

Sophos MDR hunters observed the same sideloading chains described in the BitDefender report to deploy a Merlin C2 Agent and a suspected loader for the Quarian backdoor. Due to Sophos Endpoint controls, the malicious payload was deleted before execution; however, the similarity in sideloading procedures suggests a connection between Cluster Alpha and previous BackdoorDiplomacy campaigns.

Notably, Sophos Labs documented similarities between the RUDEBIRD malware tracked by Elastic and the Impersoni-Fake-Ator malware detailed by BitDefender, suggesting a potential connection between the REF5961 intrusion set and the Backdoor Diplomacy actor. While this is a noteworthy relation, we acknowledge additional observations and samples are needed to confirm the nature of the overlap between these two reported actors with higher confidence.

Worok and TA428 Similarities

In addition, the PowHeartBeat backdoor used in Cluster Alpha has been reported by ESET to be attributed to the Worok cyberespionage group, which is noted to have possible ties to the Chinese APT TA428. Further bolstering the connection, the DOWNTOWN (PhantomNet) malware used in Cluster Alpha was also attributed to TA428 by Elastic, and Sophos observed the PhantomNet backdoor implant (sslwnd64.exe) shortly after Group-IB Threat Intelligence linked the sample to suspected TA428 activity.

Cluster Bravo

The CCoreDoor backdoor used in Cluster Bravo activity bears striking similarity to EtherealGh0st, detailed in a May 2024 report from BitDefender. EtherealGh0st is associated with a Chinese-nexus actor tracked by BitDefender as Unfading Sea Haze. The malware overlaps with CCoreDoor in its use of the CCore Library and the use of StartWorkThread to decrypt the C2 hostname and port, as well as in the commands the backdoor accepts. There is also domain overlap in the use of the C2 domain message.ooguy[.]com—Sophos MDR observed this C2 communicating with the CCoreDoor backdoor, and BitDefender reports that the domain is referenced in the EtherealGh0st sample they collected.

Additionally, BitDefender reported the first use of EtheralGh0st around mid-March 2023, which aligns with our timeline: CCoreDoor was first seen being deployed on March 14, 2023. There is also a similarity in victimology, as Unfading Sea Haze is reported to target government and military organizations from countries in the South China Sea.

Cluster Charlie

Earth Longzhi Similarities (APT41)

Though the actor operating in Cluster Charlie used a previously unreported malware family, their C2 infrastructure overlaps with reporting by Trend Micro on a group tracked as Earth Longzhi, which is a reported Chinese subgroup of APT41.

Sophos observed the PocoProxy sample 443.txt communicating with known Earth Longzhi C2 IP 198.13.47[.]158 about a month prior to Trend Micro mentioning that IP address in their report. Other infrastructure leveraged in Cluster Charlie aligns with Earth Longzhi’s previous infrastructure patterns as well – specifically the use of variations on the speedtest[.]com domain. In this intrusion, we have observed the use of both googlespeedtest33[.]com and <victim name>speedtest[.]com. Similarly, two separate Trend Micro reports (, ) have detailed Earth Longzhi registering speedtest[.]com C2 domains with a similar format (vietsovspeedtest[.]com and evnpowerspeedtest[.]com).

Cluster Overlap

While the evidence portrays three distinct sets of TTPs operating at separate times with custom tooling, there are also notable overlaps between them. For example, there were some instances of the clusters using the same credentials, such as the actors in Cluster Alpha and Cluster Bravo using the same insecure administrator account (which was also compromised in an internal penetration test) to perform actions on different systems.

Additionally, while the clusters were active on different endpoints, they did target multiple of the same primary servers and domain controllers. However, they were rarely active on the same server on the same day, and as detailed previously, temporal analysis of the clusters’ activity indicates a correlating dynamic in the timing of their operations.

Analyzing the Overlap

In our analysis of the clusters and the relations between them, we found ourselves in a comparable situation to Cybereason’s Nocturnus Team, who conducted a comparable clustering effort in 2021 focused on Chinese targeting of telecommunication companies. As mentioned, there can be many challenges in determining the nature of overlaps between clusters, and there are always “what ifs?” that play into identifying what is going on behind the intrusion activity in a network.

In this case, the activity clusters were observed in the same organization, during the same time frame, and even on the same endpoints. As a result, determining “who did what” can be a challenging task. The analysis becomes even more complex when considering Chinese state-sponsored threat groups are commonly known to share infrastructure and tooling.

While the clusters exhibit distinct patterns of behavior, the delineations in the timing of the clusters’ operations, the overlaps in compromised infrastructure, and similarities in their objectives suggest a connection between them. However, since we cannot determine with high confidence what is going on behind the scenes, we offer two plausible hypotheses that could explain the dynamic between the observed clusters:

- The observed clusters reflect the operations of two or more distinct actors working in tandem with shared objectives

- The observed clusters reflect the work of a single group with a large array of tools, diverse infrastructure, and multiple operators

Currently, most of our evidence points to the first hypothesis being the most likely based on the level of coordination we have observed; however, we acknowledge more information is needed to confirm that assessment with higher confidence. These may evolve as our intelligence collection continues and new evidence emerges that may provide further insight into the identities and relations of the observed clusters.

Conclusions

Based on our analysis, we assess with moderate confidence that multiple distinct Chinese state-sponsored actors have been active in this high-profile Southeast Asian government organization since at least March 2022. Though we are currently unable to perform high-confidence attribution or confirm the nature of the relationship between these clusters, our current investigation suggests that the clusters reflect the work of separate actors tasked by a central authority with parallel objectives in pursuit of Chinese state interests.

While this report is focused on Crimson Palace activity through August of 2023, we continue to observe related intrusion activity targeting this organization. Following our actions to block the actors’ C2 implants in August, the threat actors went quiet for a several week period. Cluster Alpha’s last active known implant ceased C2 communications in August 2023, and we have not seen the cluster of activity re-emerge in the victim network. However, the same cannot be said for Cluster Charlie.

After a few weeks of dormancy, we observed the actors in Cluster Charlie re-penetrate the network via a web shell and resume their activity at a higher tempo and in a more evasive manner. They began performing actions on objectives within the network, including exfiltration efforts in November [link to section in second post]. Additionally, instead of leaving their implants on disks for long periods of time, the actors used different instances of their web shell to re-penetrate the network for their sessions and began to modulate different C2 channels and methods of deploying implants on target systems.

Sophos MDR threat hunters continue to monitor and investigate intrusion activity in this network, and we continue to share intelligence with the community.

This cyberespionage campaign was uncovered through Sophos MDR’s human-led threat hunting service, which plays a critical role in proactively identifying threat activity. In addition to augmenting MDR operations, the MDR threat hunting service feeds into our SophosLabs pipeline to provide enriched protection and detections.

The investigation into the campaign demonstrates the importance of an efficient intelligence cycle, outlining how a threat hunt spawned from a raised detection can generate intelligence to develop new detections and jumpstart additional hunts.

Acknowledgements:

Sophos X-Ops acknowledges the contributions of Colin Cowie, Jordon Olness, Hunter Neal, Andrew Jaeger, Pavle Culum, Kostas Tsialemis, and Daniel Souter of Sophos Managed Detection and Response, and Gabor Szappanos, Andrew Ludgate, and Steeve Gaudreault of SophosLabs to this report.