A doubled “Dragon Breath” adds new air to DLL sideloading attacks

Credit to Author: Gabor Szappanos| Date: Wed, 03 May 2023 10:00:12 +0000

We have spotted malicious DLL sideloading activity that builds on the classic sideloading scenario, but adds complexity and layers to its execution. Moreover, our investigation indicates that the responsible threat actor(s) fell so much in love with this adaptation of the original scenario that they used multiple variations of it, repeatedly swapping out a particular component in the process to evade detection at this step of the attack chain.

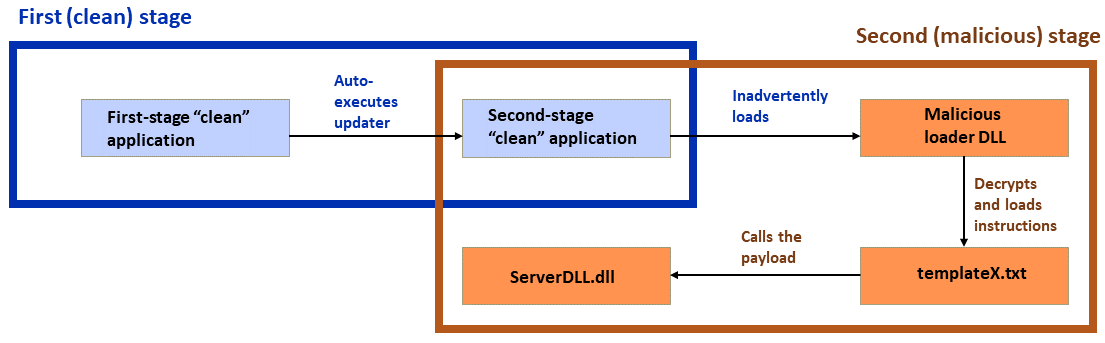

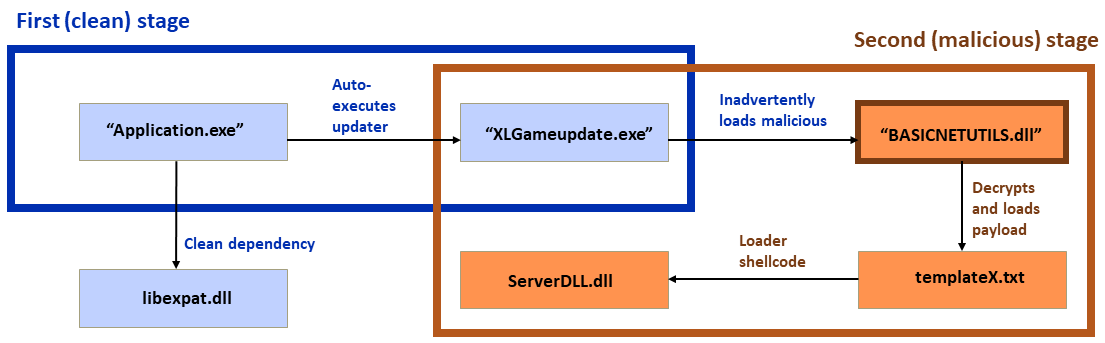

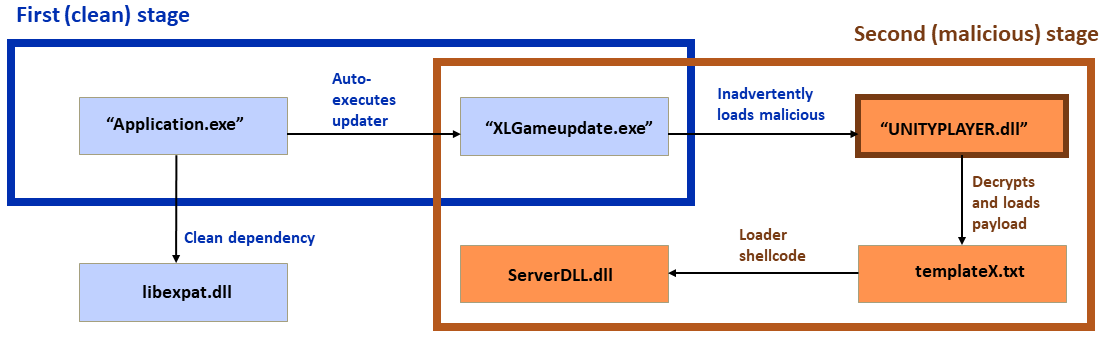

Earlier forms of the attack have been covered previously in the industry, mainly in the Sinophone CTFIoT and Zhizu blogs. The attack is based on a classic sideloading attack, consisting of a clean application, a malicious loader, and an encrypted payload, with various modifications made to these components over time. The latest campaigns add a twist in which a first-stage clean application “side”loads a second clean application and auto-executes it. The second clean application sideloads the malicious loader DLL. After that, the malicious loader DLL executes the final payload.

Figure 1: DLL sideloading, with recently identified extra steps; the clean applications are shown in blue boxes and within the blue outline, while the malicious steps are shown in orange boxes with red type and outlined in red. This chart will appear again in the report with the specifics of each variation highlighted

The threat actor most associated with this attack is variously called “Operation Dragon Breath,” “APT-Q-27,” or “Golden Eye Dog,” and is believed to specialize in the online-gambling space and its participants. These actors liked this two-clean-apps scenario so much that they used multiple scenarios in which the second-stage application is replaced with other clean applications.

The original campaigns targeted Chinese-speaking Windows users engaged in online gambling, and initial infection vectors were distributed via Telegram. We have, to date, identified intended targets in the Philippines, Japan, Taiwan, Singapore, Hong Kong, and China. Sophos normally blocks sideloading attacks during the sideloading process, so the payload never executes and the users are protected.

Figure 2: Where we saw Operation Double Dragon Breath

In this investigation we found several distinct variations on the double-clean-installer approach; variations mainly involved changes to precisely which program was abused in the second stage, with a few knock-on effects caused in turn by those changes. We’ll describe the most commonly encountered code we found at each stage, touching on variations as we go along.

The beginning: Infection vector

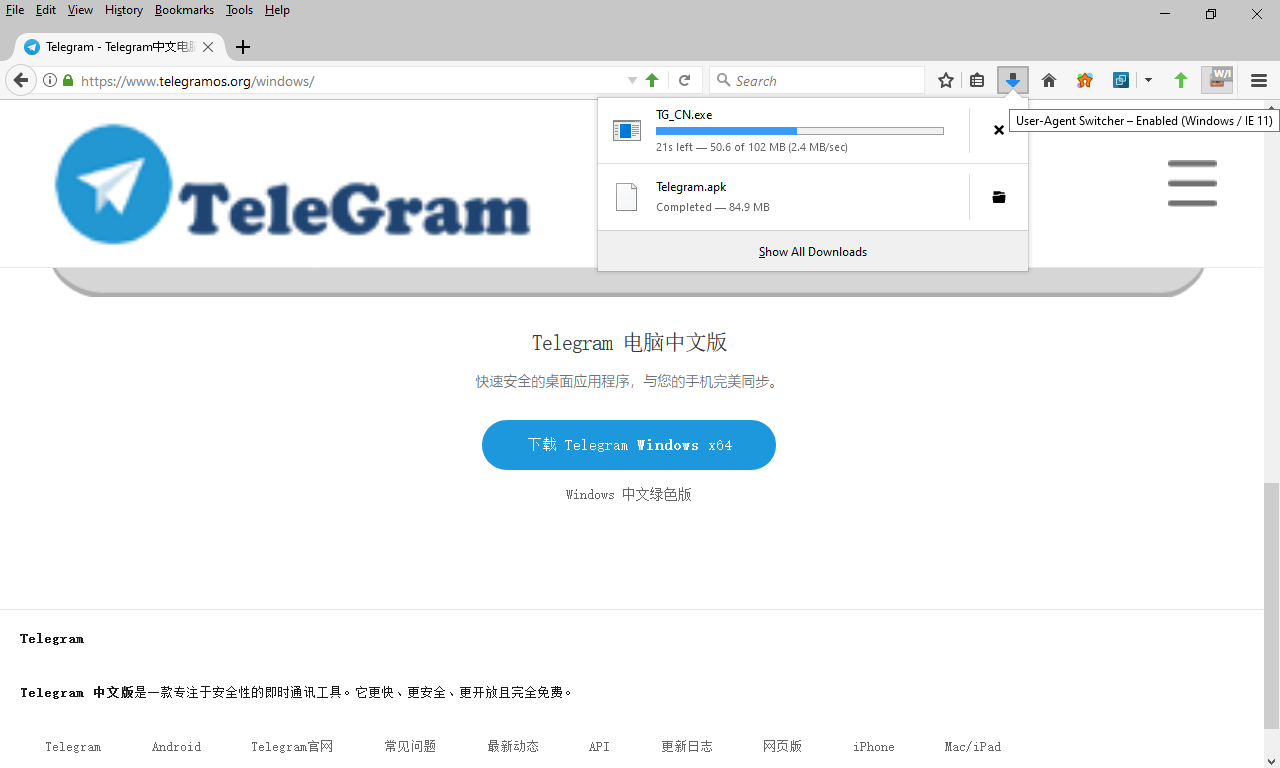

Early on, our investigation led us to a Web site (telegramos[.]org) that delivers, or claims to deliver, Chinese-language versions of the Telegram application for Android, iOS, and Windows. We noted that the site — which we and other vendors flag as malicious — occasionally but not consistently ignored our OS choices when we clicked the download links, instead delivering a version based on the user-agent string to which our browser was set, as shown in the screen captures below.

Figure 3: Clicking the ‘Windows” button from the Windows download page meant nothing when our browser reported itself as Android…

Figure 4: …so we changed our UA string to IE

This is the site from which the affected user is thought to have downloaded the package that caused the infection. How the user first encountered the site, whether through phishing or SEO poisoning or some other method, is beyond the scope of this investigation.

First-stage installer: Telegram

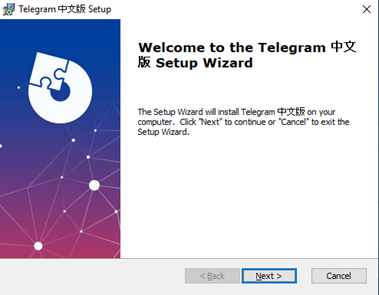

As mentioned above, the initial investigation of these attacks involved a malicious Telegram installer. Later in this article we’ll see variations in which other “lure” applications were used, but Telegram was by far the most common lure, and dissecting it provides a good example of how the attack works.

When the malicious Telegram installer (SHA256: 097899b3acb3599944305b064667e959c707e519aef3d98be1741bbc69d56a17) is run, it installs and executes the sideloading package.

Figure 5: This setup screen is actually an evil wizard

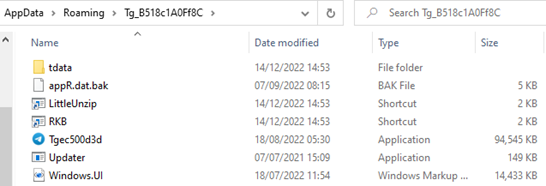

It installs multiple components on the system, dropping them to a directory in the user data folder:

Figure 6: Gifts of the evil setup wizard

It also creates a shortcut on the desktop. However, this shortcut does not execute the Telegram program, but an unusual command:

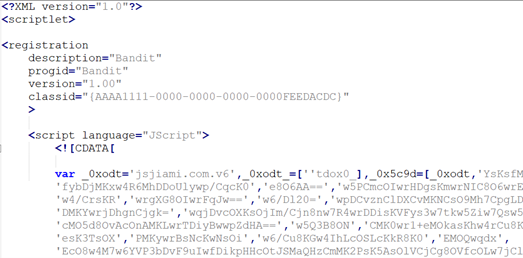

C:Users{redacted}AppDataRoamingTg_B518c1A0Ff8CappR.exe /s /n /u /i:appR.dat appR.dllHere appR.exe is the regsvr32.exe Windows component, renamed. It will execute the appR.dll library, which is another renamed Windows component, scrobj.dll — the script execution engine. It will then execute the Javascript code stored in appR.dat:

Figure 7: Its reg description is Bandit, which is accurate

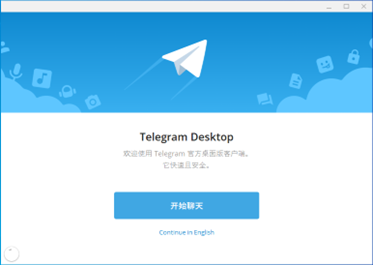

When the shortcut is executed, the JavaScript code runs. To the user, it displays the expected Telegram desktop UI, mostly in Chinese:

Figure 8: A mostly transliterated version of the Telegram desktop UI

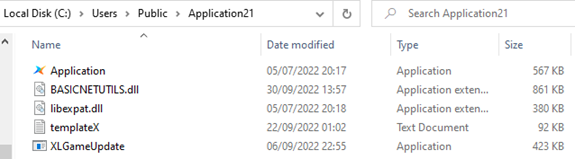

But behind the scenes it drops various sideloading components to a directory:

Figure 9: A directory with problematic files deposited in it

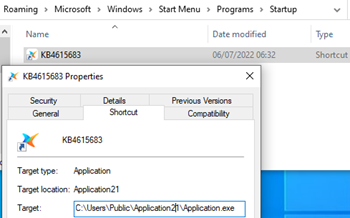

The installer also creates a shortcut file in the user’s startup directory. In this way, the malware establishes persistence and allows for automatic execution after system startup.

Figure 10: A fairly innocuous-looking shortcut is anything but; note “Application.exe,” which we’ll see again in the next stage of the attack

The sideloading components and the startup link are only created when the desktop Telegram link is executed. This could be an anti-analysis trick, since dynamic analysis sandboxes would not see the dropped sideloader files.

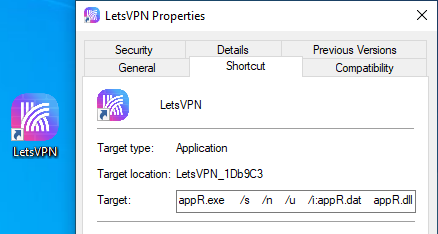

A first-stage variation: LetsVPN installer

We also found a trojanized installer for LetsVPN (SHA256: e414fc7bcd80a75d57ee4fdbb1c80a90a0993be8e8bbbe0decfc62870a2e1e86). The malicious parts of the package are the same as in the Telegram cases, but the bundled clean application is LetsVPN:

Figure 11: The LetsVPN variation we found is translated into Chinese on its initial screen, but the installation screen is in English

As the Telegram installer did, it creates a shortcut on the desktop. The program that the shortcut launches invokes the JavaScript code that does the ultimate installation of the sideloading package.

Figure 12: The icon has changed, but the application to which it truly points remains the same

One more first-stage variation: WhatsApp installer

In one case, we did not have direct contact with the installer file, but our telemetry shows that running a file called Whatsapp.msi also leads to the installation of the malicious files we saw in the other two first-stage examples.

roamingwhatsapp_ae2b02appmain.exe : 91e4eb7517f55ac93b1da109539aa0011e9346be41704dc0da360ebad0f3f63d roamingwhatsapp_ae2b02appr.dll : e25289d44403a6f6132a470fdbe6b46eade466d08eca0ad44fca519592c54fdf roamingwhatsapp_ae2b02appr.exe : fffa7a97fba9dfb235f969ecce0e5c4a71a48a37c1bc79b77cd78f0ab72f993d roamingwhatsapp_ae2b02littleunzip.exe : 81046f943d26501561612a629d8be95af254bc161011ba8a62d25c34c16d6d2a roamingwhatsapp_ae2b02app-2.2232.8whatsapp.exe : 8d92c7d7f301bc0e4965dbd9253933a4580883805119dd7c27788d04c17d595e c:userspublicapplication2application.exe : c936f1598721a9a92d7f31c6c13b55013b8a2a344e3df4156e5b033006336544 c:userspublicapplication2xlgameupdate.exe : 769d59d03036af86c7a9950f03ebc7b693a94d3e2f8ecd1d74cf5600ab948105 c:userspublicapplication2libexpat.dll : 31d2076066107bd04ab24ff7bbdf8271aa16dd1d04e70bd9cc492e9aa1e6c82b c:userspublicapplication2basicnetutils.dll : ae2e145b36ab2ed129a2d34de435b76a1f4e5a4820d9d623e7018b87f24d0648

Second stage: More sideloading

As mentioned, one of the most exciting things about this investigation was spotting a new variation on DLL sideloading – the use of a second “clean” application as a secondary stage in the attack. In these unusual attacks, the beginning (first-stage loader) and the end (payload) were the same; the only difference was in this second-stage sideloading.

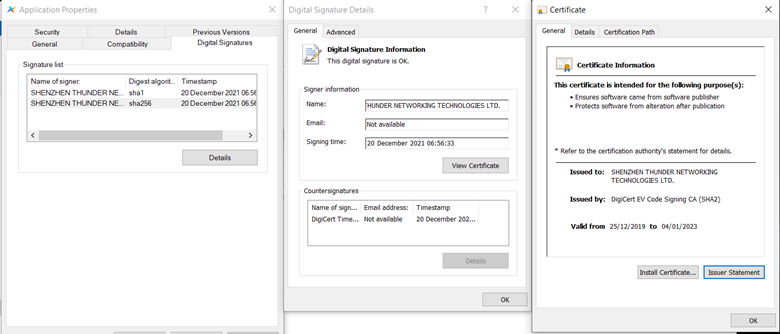

In Figure 8 above, we pointed out “Application.exe,” for which the installer left a shortcut on the desktop. In Figure 11 we see it again. It’s actually the program XLGame.exe, signed by Shenzhen Thunder Networking Technologies Ltd, but renamed by the attackers to Application.exe. It has a clean dependency, libexpat.dll, which is part of the package.

Figure 13: The attackers used a clean-but-vulnerable application (named “Application.exe” on the desktop, but really XLGame.exe) that auto-updates itself if it finds a file with a specific name. The names of malicious files are shown in the orange boxes to the right as before, and files renamed by the attacker are shown in quotation marks

Figure 14: XLGame’s digital signatures would seem to indicate everything is in order, despite being renamed to Application.exe

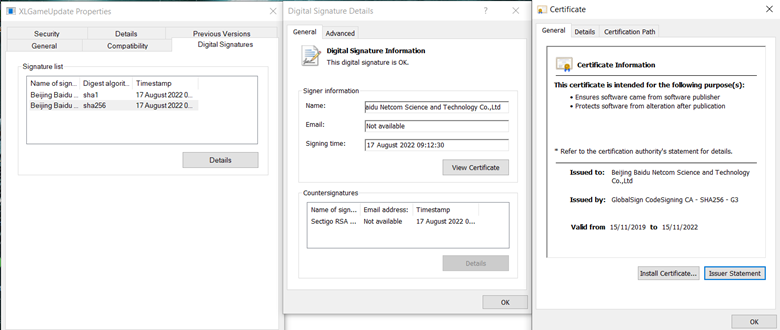

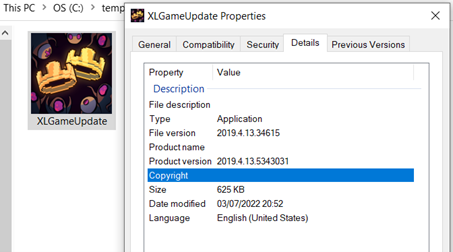

XLGame will automatically perform an automatic update if it finds a program named XLGameUpdate.exe in the same directory. The loading process makes use of this auto-update functionality, as the malicious package contains an executable with this name — but it’s not the real XLGameUpdate.exe. Rather, it is a clean, signed .exe from Beijing Baidu Netcom Science and Technology Co.,Ltd.

Figure 15: XLGameUpdate.exe is actually a different, unnamed application, but renamed to trick “Application.exe” (really, XLGames.exe) into running it

And now we return to the usual DLL-sideloading process. This second-stage loader has a dependency, BASICNETUTILS.dll, which the attackers have replaced with a malicious loader DLL. The malicious loader DLL finds templateX.txt in the same directory, loads the content, decrypts the payload loader shellcode, and executes it. (All these files are of course located in the same directory, as seen in Figure 7 above.)

Second stage: More sideloading (a variation)

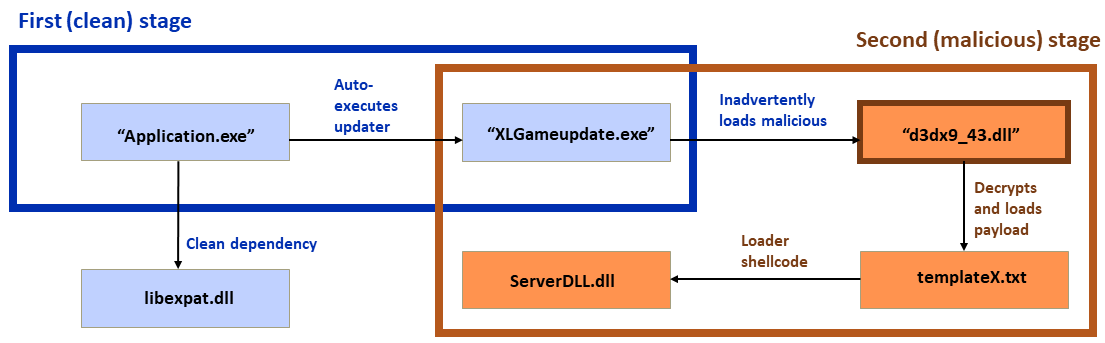

As noted in the introduction, the attackers appear to be very fond of their double-dip DLL sideloading strategy, swapping various clean apps into the new spot in the sideloading process. Figure 16 shows a flow very similar to the previous scheme, but the clean executable is different in the second-stage loader. Consequently, the malicious loader DLL has to be renamed to reflect the dependency of the replaced clean application.

Figure 16: The attackers are running the same extra-step playbook as in Figure 13, but they’ve swapped in a new program in the “XLGameUpdate.exe” spot; by extension, the to-be-swapped DLL shown at upper right must change as well. Again, the names of malicious files are shown in the orange boxes to the right, and files renamed by the attacker are shown in quotation marks

As before, “Application.exe” is actually XLGames.exe. The second-stage clean loader is renamed once again to XLGameUpdate.exe, but its original (real) name is KingdomTwoCrowns.exe. It is not digitally signed, so it’s not clear what the benefit might be of replacing the clean, signed loader from Baidu with this one.

Figure 17: It’s still not XLGameUpdate, but this time it’s actually “KingdomTwoCrowns”

It has the following PDB path:

C:buildslaveunitybuildartifactsWindowsPlayerWin32_nondev_i_rWindowsPlayer_Master_il2cpp_x86.pdb

This second-stage loader is used for the usual sideloading scenario; its dependency, UNITYPLAYER.dll, is replaced with a malicious loader DLL. The malicious loader finds templateX.txt in the same directory, loads the content, decrypts the payload loader shellcode, and executes it.

Thus, the second-stage clean loader is different, but the second-stage malicious loader and the payload files in this variation are essentially the same as in the variation described in the previous section (aside from being renamed). In fact, one of the encrypted payload files (3fc9405cfe9272323bd96aacfd082c16b392fea6e0f108545138026aa6f79137) was used in both scenarios. (We’ll discuss the payload in the final section of this article.)

Second stage: More sideloading (one more variation)

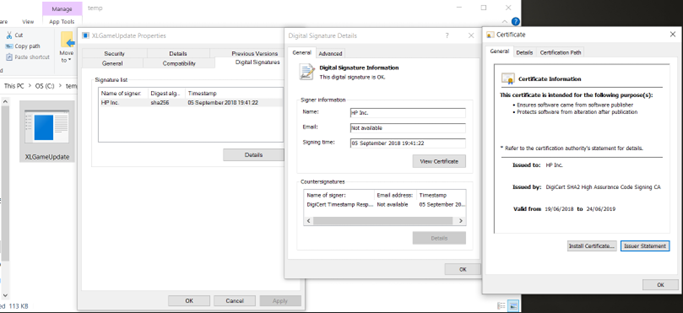

Once again, this scenario swaps out the clean executable in the second-stage loader, this time abusing a clean, digitally signed tool once offered by HP. This is very similar to the previous scheme, but since the clean executable is once again different in the second-stage loader, the malicious loader DLL has to once again be renamed to reflect the different dependency.

Figure 18: One more variation on the double-dip sideloading theme, with an HP tool in the XLGameUpdate spot at center-top and yet another DLL in the highlighted malicious spot at upper right. Once again the names of malicious files are shown in the orange boxes to the right, and files renamed by the attacker are shown in quotation marks

The second-stage clean loader is again renamed to XLGameUpdate.exe. Its original name is d3dim9.exe. It is digitally signed by HP Inc.

Figure 19: This time, the application renamed as XLGameUpdate is really a signed, clean application from HP

This second-stage loader is used for the usual sideloading scenario. Its dependency, d3dx9_43.dll, is replaced with a malicious loader DLL. That DLL finds templateX.txt in the same directory and – once again — loads the content, decrypts the payload loader shellcode, and executes it.

Third stage: At last, the malicious DLL

The second-stage loaders had interesting variations, but all roads lead to one thing: cryptowallet theft. To that end, the payloads we saw in this investigation were fairly constant.

At the end of stage 2, the clean second-stage loader (whichever one is in use) calls a specific DLL – and get the malicious, identically named version the attackers have placed in the same directory, in the classic DLL-sideloading fashion. The malicious DLL loads the payload from the file template.txt, then decrypts it.

The payload’s encryption is a simple combination of bytewise SUB and XOR:

int __fastcall decrypt(int a1, int a2) { int result; // eax for ( result = 0; result < a2; ++result ) *(_BYTE *)(result + a1) = (*(_BYTE *)(result + a1) - 122) ^ 0x19; return result;

The decrypted content is a loader shellcode, which decompresses and executes the final payload. This execution log shows this decompression of the final payload:

4010ae GetProcAddress(LoadLibraryA) 4010ae GetProcAddress(VirtualAlloc) 4010ae GetProcAddress(VirtualFree) 4010ae GetProcAddress(lstrcmpiA) 401153 LoadLibraryA(ntdll) 4010ae GetProcAddress(RtlZeroMemory) 4010ae GetProcAddress(RtlMoveMemory) 40148e VirtualAlloc(base=0 , sz=20a00) = 600000 401635 GetProcAddress(LoadLibraryA) 401697 LoadLibraryA(ntdll) 401635 GetProcAddress(RtlDecompressBuffer) 4016bd RtlDecompressBuffer(fmat=102,ubuf=600000, usz=20a00, cbuf=4016e3, csz=16789) (Outsz: 20a00) = 0 4011e2 VirtualAlloc(base=0 , sz=26000) = 621000 4011f9 RtlMoveMemory(dst=621000, src=600000, sz=400) 401235 RtlMoveMemory(dst=622000, src=600400, sz=17e00) 401235 RtlMoveMemory(dst=63a000, src=618200, sz=4c00) 401235 RtlMoveMemory(dst=63f000, src=61ce00, sz=1800) 401235 RtlMoveMemory(dst=643000, src=61e600, sz=200) 401235 RtlMoveMemory(dst=644000, src=61e800, sz=2200) 4012ed LoadLibraryA(KERNEL32.dll)

Figure 20: The decompression of the final payload

After this, the shellcode loads the final payload DLL into memory and executes it.

Fourth stage: The payload

The payload DLL contains one export, rudely named:

dllname: ServerDll.dll 0 1 0x14780 0x15380 F■ck

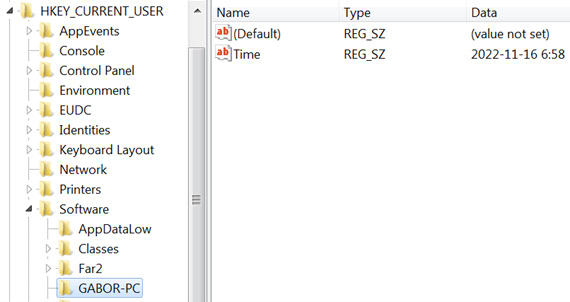

This creates a flag key in the registry. The name of the key will be HKCUSOFTWARE%COMPUTERNAME%, if GetComputerName returns a value; otherwise UnkNow will be used.

Figure 21: The flag key picked up the name of the machine on which this exploit was dissected

Multiple values are stored under this key:

- Time: records the date and time of installation of the malware

- CopyC: updated C2 address (encoded with bytewise XOR 5 + BASE64)

- ARPD: list of names, separated with | . creates new thread for each; searches for strings isARDll, PluginMe, getDllName – may be export names

- ZU: value is used in the procedure that reads the wallet seed for the Chrome extension; likely provides destination information for exfiltration of wallet contents

- Remark: stores the hostname

The backdoor supports a set of numeric command codes:

It also contains a string related to MetaMask. MetaMask is a crypto (Ethereum) wallet available as, among other things, a Chrome extension. In the past, attackers looking to steal from cryptowallets have targeted users who have installed this extension, and that’s what appears to be happening here.

C:Users%sAppDataLocalGoogleChromeUser C:Users%sAppDataLocalGoogleChromeUser DataDefaultExtensionsnkbihfbeogaeaoehlefnkodbefgpgknn

The C2 server name, nsjdhmdjs[.]com, has been associated with Operation Dragon Breath (aka “APT-Q-27” or “Golden Eye Dog,” as above). Some of the DLL sideloading characteristics we’ve demonstrated and also the ServerDll.dll name are likewise characteristic of this threat actor.

Fourth stage: Payload variations – a debug build version and the gh0st of a sample

We also found, on VirusTotal, a specific version of the payload (SHA256: d86f1292d83948082197f0a29fcb69fdec9feb4bf3898d7b8e693c7d5a28099c) that contained more internal information than usual. This is also an executable, unlike the usual payloads (which are DLLs).

The PDB path is the usual:

D:Work3远控企业远程控制DebugServerDll.pdb

In this case, however, it contains the source code of the infamous gh0st RAT. The source archive is supposed to be dropped by one of the procedures, but that code is never executed:

hFile = CreateFileA(lpFileName, 0x40000000u, 1u, 0, 2u, 0, 0); if ( hFile == (HANDLE)-1 ) v4 = 0; if ( WriteFile(hFile, &gh0st_rat_src, 0xE5B1Au, &NumberOfBytesWritten, 0) ) v4 = 1; CloseHandle(hFile); return v4;

For this sample, the C2 server is 23[.]225[.]147[.]227.

We also saw on VirusTotal a similar sample (sha256: 64613eadd91a803fe103bef5349db04ddfc01b8d115ba7a24a694563123d38ad) that contained gh0st RAT source code, but no debug information and no PDB information. Both these debug versions were submitted to VirusTotal from Hong Kong, one of the regions known to be affected, so it is likely they were indeed used in attacks.

A full list of IoCs is available on our GitHub.

Conclusion

DLL sideloading, first identified in Windows products in 2010 but prevalent across multiple platforms, continues to be an effective and appealing tactic for threat actors. This double-clean-app technique employed by the Dragon Breath group, targeting a user sector (online gambling) that has traditionally been less scrutinized by security researchers, represents the continued vitality of this approach. While speculation about future uses of the technique is beyond the scope of this post, it may be useful for defenders to keep an eye out for the behavior we’ve documented here.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Xinran Wu of SophosLabs and Andrew Brandt of X-Ops Comms for their assistance on this writeup.