The scammers who scam scammers on cybercrime forums: Part 4

Credit to Author: Matt Wixey| Date: Wed, 28 Dec 2022 12:00:01 +0000

It’s the last chapter in our ‘Scammers who scam scammers’ series! (Missed the previous instalments? Part 1 introduced the ecosystem, Part 2 looked at the different types of scams, and Part 3 covered a specific, large-scale scam.). In this final article, we’ll look at why scammers on criminal marketplaces (inadvertently) provide useful strategic and tactical intelligence.

Many criminal marketplaces demand proof when a scam is alleged, and victims are only too happy to oblige. While a minority of reporters redact this evidence, or restrict it so it’s only visible to a moderator, most don’t – and sometimes leave a treasure trove of cryptocurrency addresses, transaction IDs, email addresses, IP addresses, victim names, source code, and other information.

This is in contrast with other areas of criminal marketplaces, where operational security is often very good. Maybe scam victims assume nobody is paying attention to arbitration rooms – or they’re so ticked off about being scammed that their usual precautions take a backseat.

To give you an idea of how prevalent this is, we looked at the most recent 250 scam reports on all three forums. 39% included screenshots, and 53% contained text-only accounts of the incident (often going into considerable detail). Only 8% of reports restricted access to evidence, or offered to submit it privately to an arbiter.

Receipts

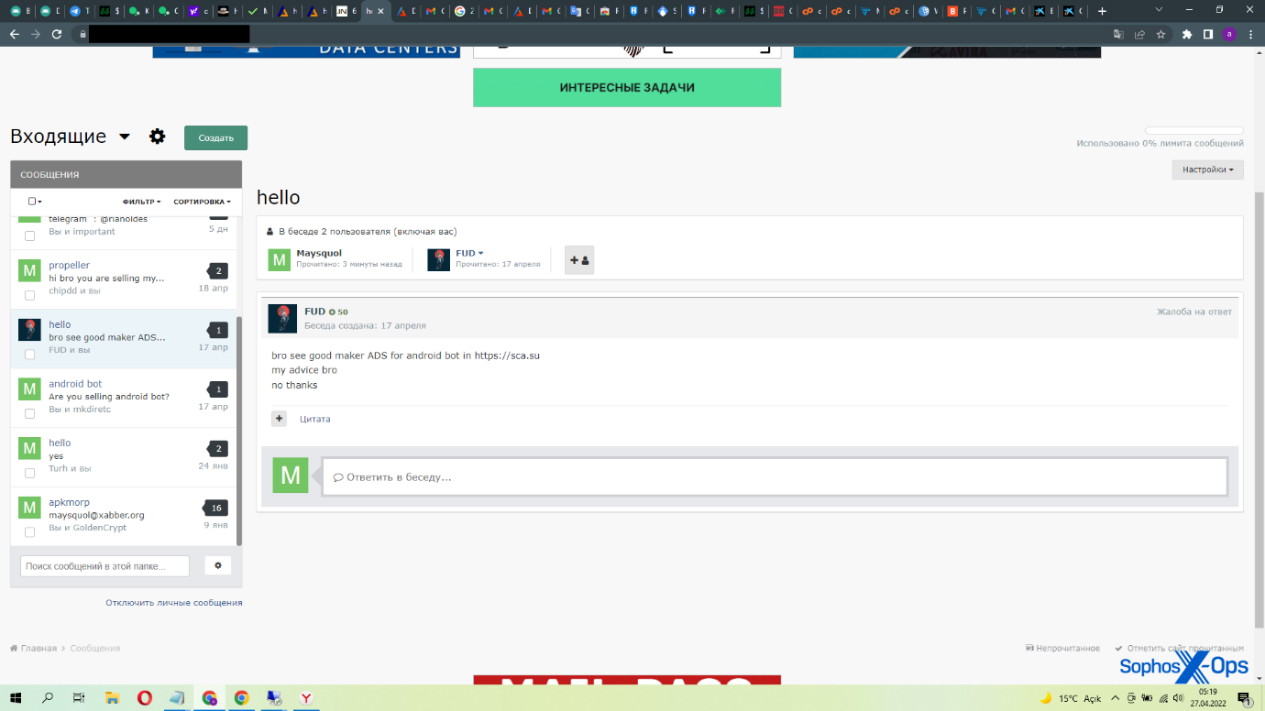

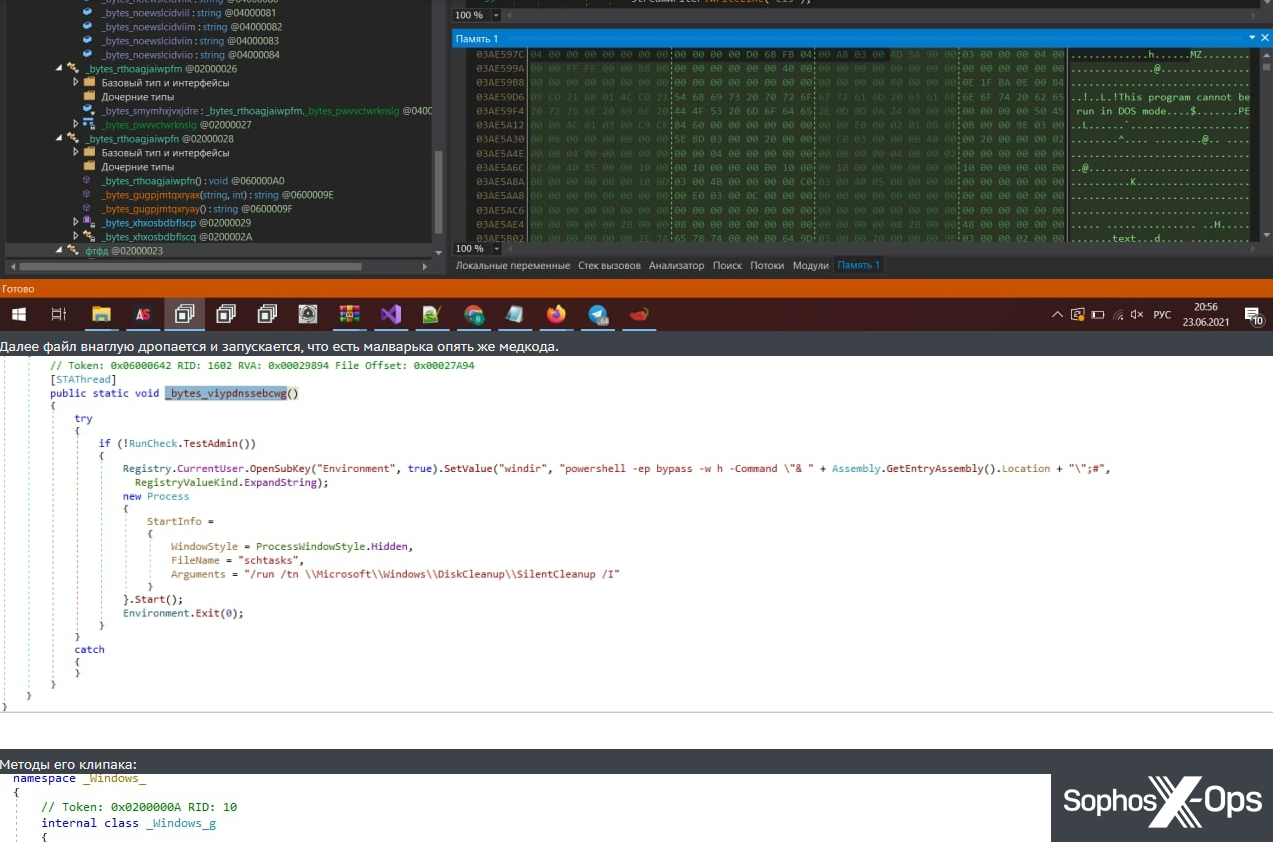

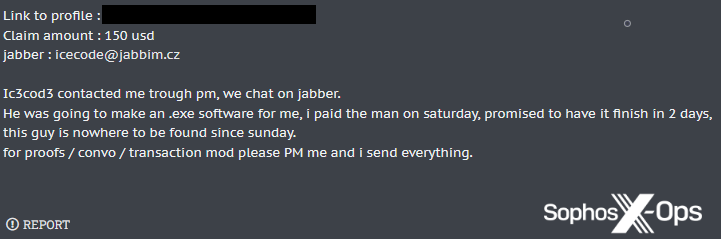

Here’s a typical scam report with evidence (we’ve redacted the forum’s address, which appears as a watermark on uploaded images, but the screenshots themselves are unredacted). The attachments include private messages on two platforms, as well as identifiers.

Figure 1: A typical scam report, with proof

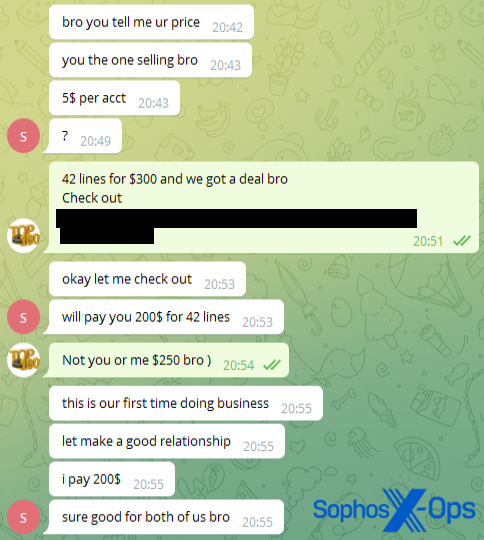

Here’s just a small selection of the kinds of things we saw in screenshots and chat logs.

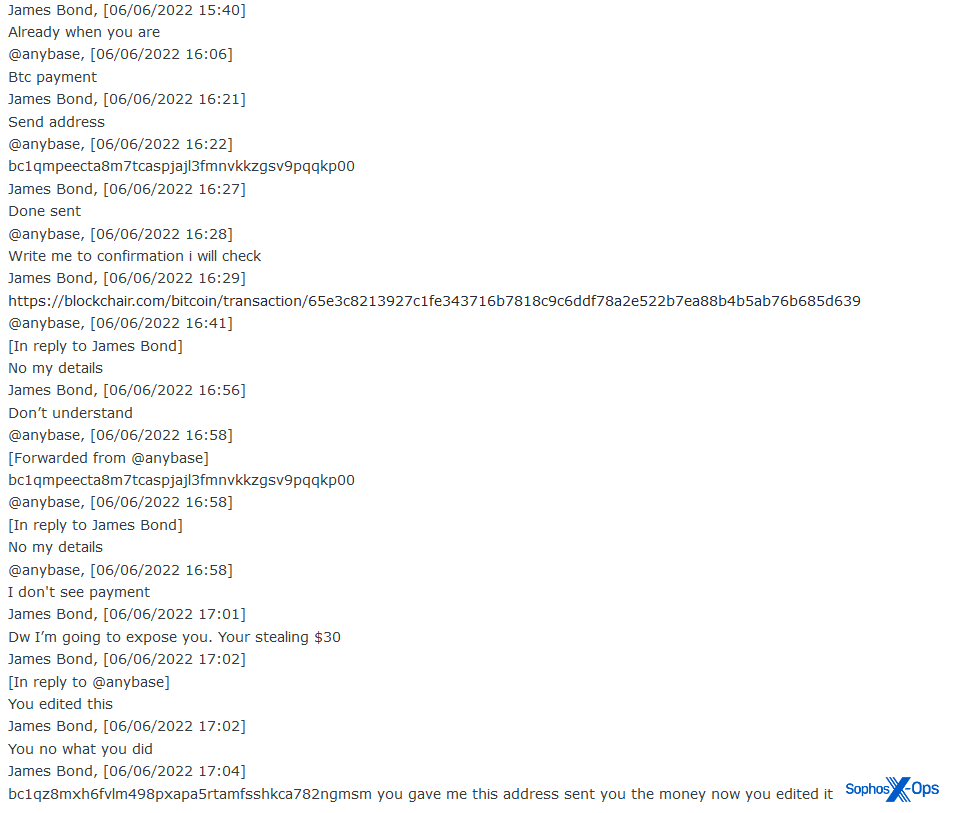

Bitcoin addresses and transaction details

Criminal marketplaces often serve as advertising boards, with negotiations and sales usually occuring in other channels, such as Telegram, Tox, forum DMs, and so on. Sellers and buyers stick to this rule of thumb out of operational security concerns. But when it comes to scam complaints, these concerns can fall by the wayside. We saw numerous screenshots of negotiations and sales, complete with cryptocurrency addresses and links to transactions – which could be of significant use when investigating specific incidents or threat actors (either individuals or networks). Of course, threat actors may still apply anonymizing measures to their transactions, but it’s better than nothing.

Figure 2: In this screenshot of a chat log, the scam victim posts a transaction link (containing their Bitcoin address)

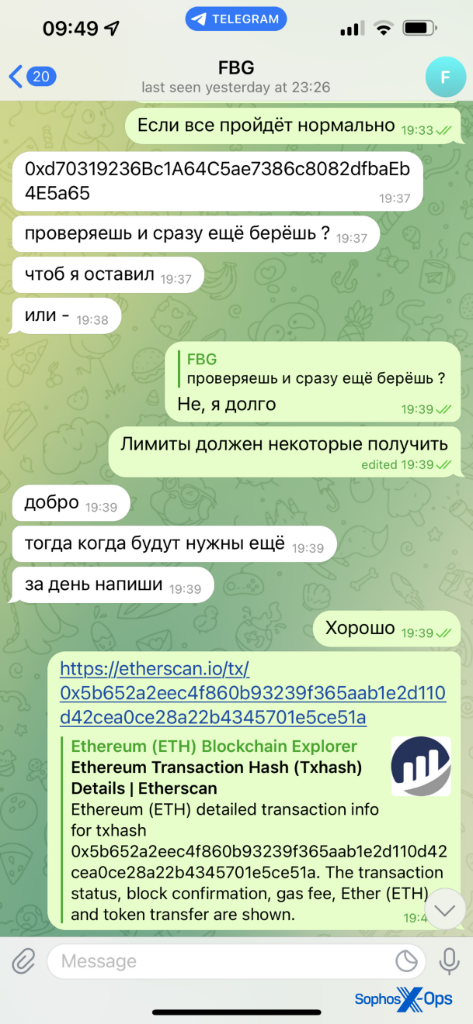

Figure 3: Another example of a transaction link, this one via Telegram and for Ethereum

Figure 4: Transaction details from another scam complaint. Note this screenshot also includes date, time, weather, and the user’s taskbar

Email addresses and more…

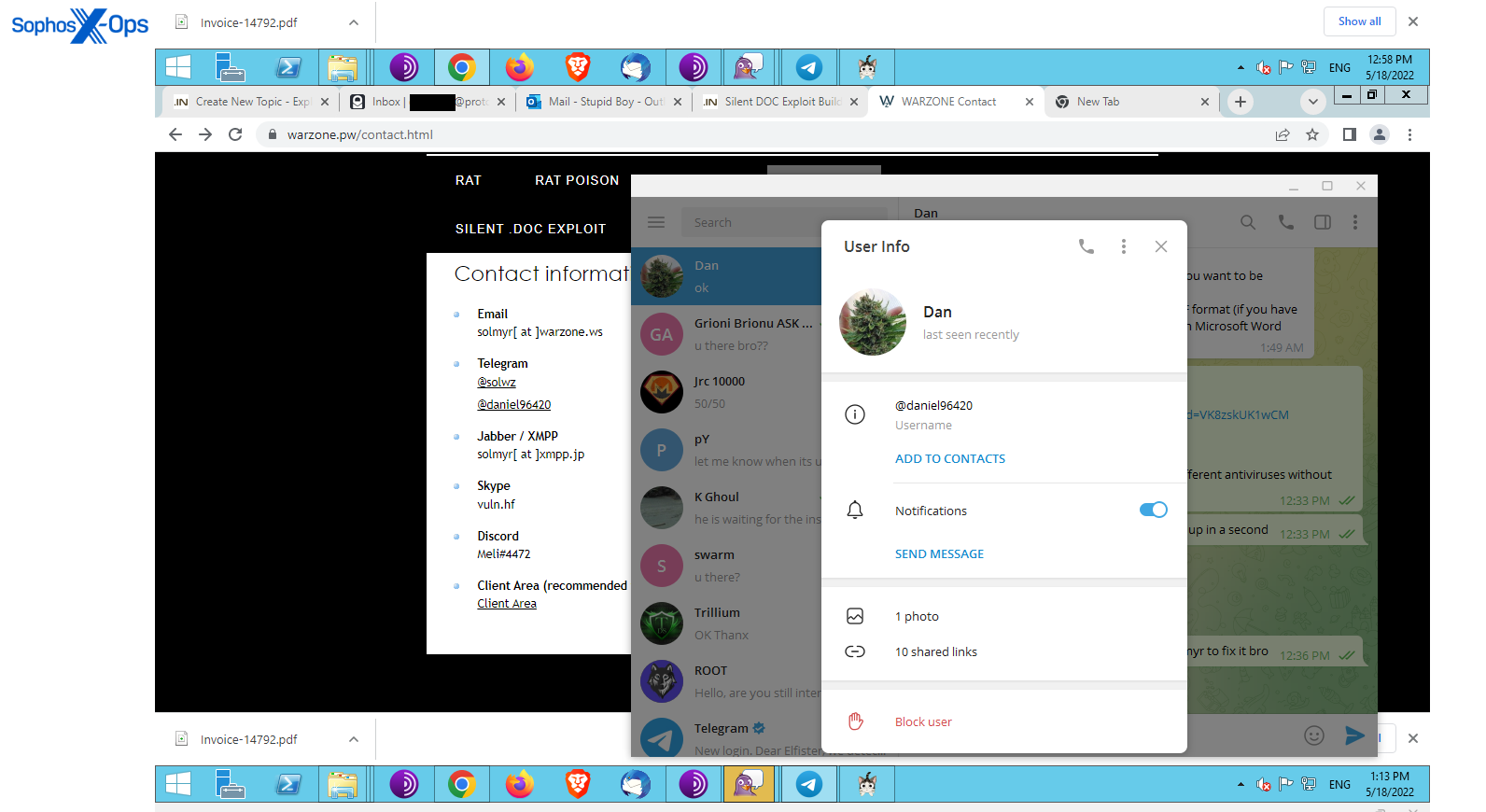

Some scam reporters are particularly lax about redacting information. In one case, a complainant uploaded a series of screenshots (an example is shown below) containing information about the applications installed on their system, the date and time, their email address, their Outlook name, and usernames of other individuals with whom they were communicating on Telegram.

Figure 5: A screenshot posted by a scam complainant, containing a wealth of information

Figure 6: An invoice for purchase of an exploit builder, posted by the same complainant

Figure 7: A screenshot posted by another scam complainant, this one relating to a ripper marketplace. Note the tabs open, the applications on the taskbar, the date/time/weather/language, and the other chats open

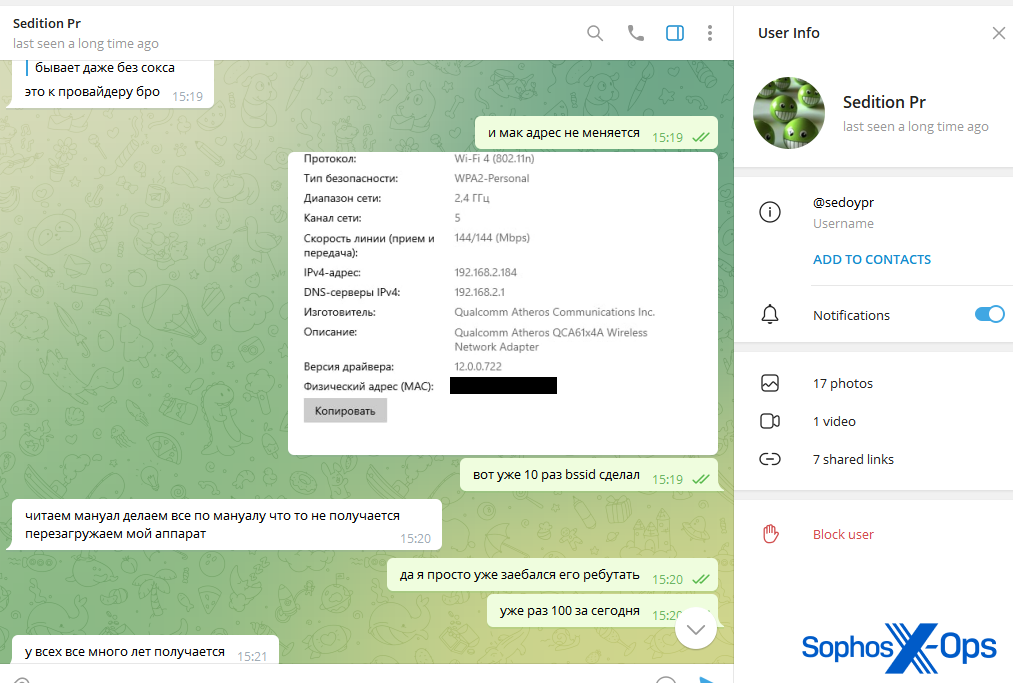

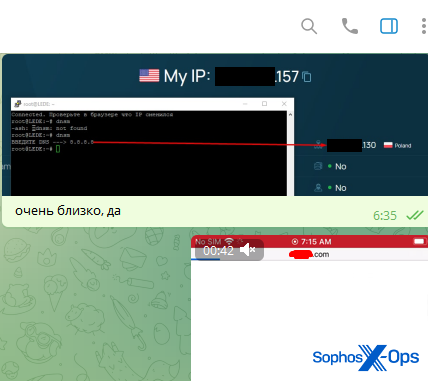

MAC and IP addresses

While not common, we did see MAC and IP addresses in complainants’ screenshots, often from troubleshooting malware or AaaS listings with an alleged scammer.

Figure 8: A scam complainant posts details of a WiFi adapter, including its MAC address

Figure 9: An excerpt from a chat log in a scam complaint, containing an IP address, country, and hostname being tested by the scammer and complainant

Figure 10: Two IP addresses revealed in a scam complaint

Malware source code

While relatively rare, we did observe at least one instance of a scam complainant sharing malware source code.

Figure 11: A screenshot of malware source code, posted as part of a scam report. Note that this screenshot also includes the Windows taskbar, which shows some of the applications installed, the language, and the date and time

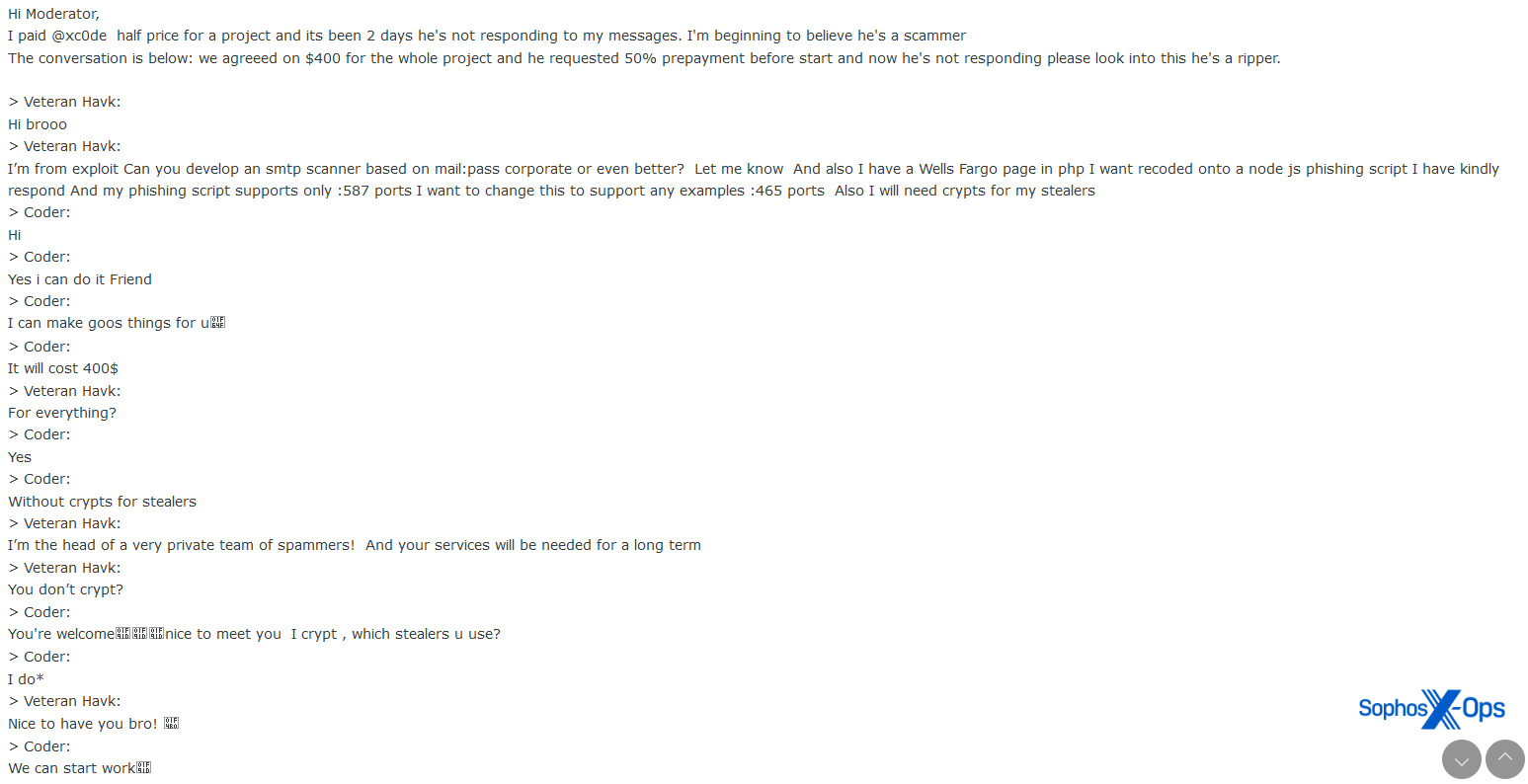

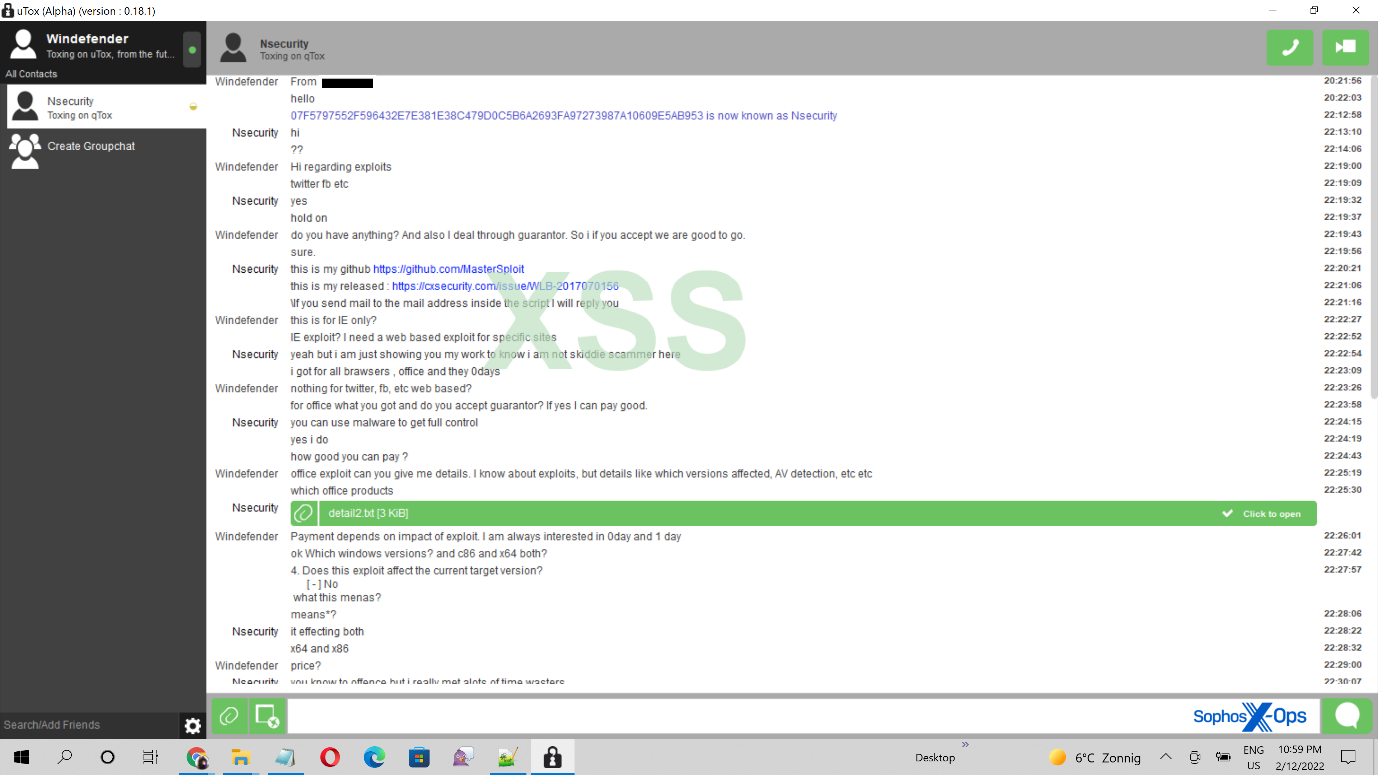

Names of victim organizations

Sellers do not typically mention victim names in their AaaS listings, as they’re concerned about organizations being tipped off. However, we saw several examples where scam complainants posted detailed chat logs, such as the one below, which included victim names.

Figure 12: An excerpt from a Tox chat log about the purchase of an AaaS listing affecting a specific, named victim (which we have redacted)

Figure 13: Excerpt from a chat containing a username, password, and organization name as a sample (which we have redacted)

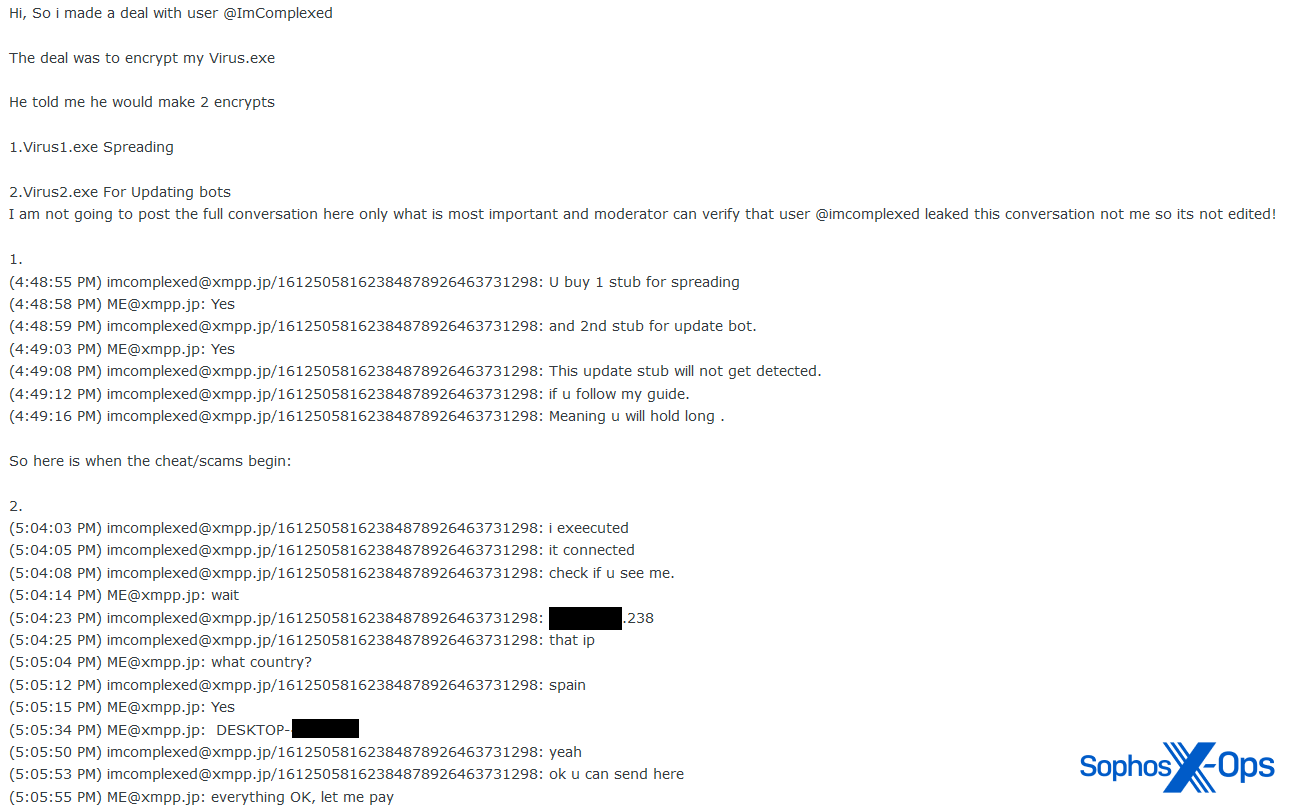

Detailed information about negotiations and planned attacks/projects

We observed several cases where scam complainants posted detailed chat logs about projects and attacks.

Figure 14: A scam complainant posts an excerpt from a chat log which reveals detailed information about the project they were working on

The example below not only includes detailed information about a possible sale of exploits (although note that this is a scam complaint), but the alleged scammer’s GitHub profile and a website featuring one of their vulnerabilities (which could be used to identify the scammer). The screenshot also shows applications installed on the complainant’s machine, their Tox name, the date and time, and the temperature and weather at the time of the post (“Zonnig” is Dutch, meaning “sunny”).

Figure 15: A screenshot of a Tox chat posted by a complainant as part of a scam report

One caveat: since these details are posted in arbitration threads, they can’t always be relied upon to be representative of the underground economy as a whole. However, they do provide a starting point. And since scam reports are created by both buyers and sellers, there’s material from ‘legitimate’ users on both sides of transactions.

It’s also worth noting that some forum users are more circumspect about the details they share in scam reports. However, in our experience these users were very much in the minority; in the scam reports we looked at, only 8% restricted access to evidence.

Figure 16: A user doesn’t share evidence in their scam report, but instead offers to share it in a private message to moderators

Conclusion

Threat actors – including some very prominent ones – don’t always practice what they preach, or learn from their victims’ mistakes. This has two important implications. First, the underground economy is riddled with a wide variety of (successful) scams, netting scammers millions of dollars a year and resulting in an effective ‘tax’ on criminal marketplaces.

And second, threat actors are not immune to deception, social engineering, and fraud – in fact, they’re as vulnerable as anyone else. So certain kinds of defensive techniques – honeypots, decoy and canary data, and similar measures – are probably worthy of more attention, investigation, and research and development.

There’s also a huge diversity of scams on criminal marketplaces. Some, like fake guarantors, are specific to those platforms, whereas others are more generic. It’s likely that there are other, more sophisticated scams running which threat actors have not yet detected and/or reported. It’s also likely that scams against threat actors will continue to develop and evolve.

While this is an interesting topic, we were initially doubtful as to whether our research could be of any practical use. However, we quickly realized there are two key applications:

1) Scam reports can be a rich source of intelligence. While threat actors on ‘elite’ criminal forums may have solid operational security, this seems to fall by the wayside when they’re scammed. We found numerous instances of sensitive data and verbose details in screenshots and chat logs attached to scam reports. In some cases, evidence included discrete identifiers which researchers could use in specific investigations. In others, it included more general information about negotiations, sales, attacks, and projects. Scam reports in general can also be useful for strategic intelligence, providing researchers with information about rivalries and alliances, wider trends, and forum culture.

2) We hope that this research will help prevent inexperienced researchers, analysts, journalists, law enforcement agents, and others who monitor criminal marketplaces from falling victim to some of these scams themselves (whether that’s giving away credentials to fake sites or paying to access ‘closed’ forums which are actually ripper sites).

Our dive into the world of scammers scamming scammers is an exploratory one, but we hope it’s the start of more research on this topic. There’s a lot more we want to investigate – including more detailed quantitative studies, looking at a broader range of marketplaces, and exploring other scamming techniques used against criminals.