Crypto, really. Part III: cryptocurrency politics, and the future | Kaspersky official blog

Credit to Author: Ivan Kwiatkowski| Date: Fri, 25 Nov 2022 14:18:00 +0000

Disclaimer: the opinions of the author are his own and may not reflect the official position of Kaspersky (the company).

The first two parts of this series established that cryptocurrencies and NFTs ended up in a place far from where they claimed they were heading. And we might as well have stopped there: after all, our initial line of questioning cynically revolved around the possibility of getting rich off NFTs. So what’s left to say now that we’ve established how unlikely getting rich is? Wouldn’t carrying on be like flogging a dead horse?

Unfortunately, the horse isn’t quite dead. Even though I might have succeeded in dissuading you from entering the cryptocurrency world, and even though that world has experienced a major crash recently, powerful forces are at work to ensure not only its survival but also its penetrating deeper into our daily lives. This is why, before we part ways, there’s one final and crucial point I need to make: cryptocurrencies don’t fulfill anything they promised; but even if they did — it would be a disaster.

The bank run

Let us start with a discussion of the current state of the cryptocurrency market. In May 2022, its capitalization fell from 1.8 to 1.2 trillion dollars, which is to say that it lost roughly the equivalent of the GDP of Poland. At the time of this writing, we’re now down to $1T. The NFT space also drastically shrunk in the first half of 2022 — triggered by severe blows to the ecosystem, in which major actors experienced liquidity problems. This November, one of the biggest exchanges in the world — FTX — filed for bankruptcy, and its management is facing accusations of gross misconduct. With liabilities of $10-50 billion, FTX’s fall is sure to change the crypto landscape forever. But 2022 had already been a rough year: stablecoins such as Tether or Terra — crypto-assets attempting to maintain parity with the US dollar — had already faced severe difficulties. Stablecoins offer a low-volatility (ideally, no-volatility) way of storing capital without leaving the cryptocurrency space. If you expect Ethereum to go down, you can exchange all your reserves against their equivalent amount in stablecoin, and buy Ethereum again at a lower price later. The process is quicker and cheaper than having to cash out to dollars — even temporarily.

The exchange rate of Bitcoin over the last year Source

Obviously, the stablecoins’ one-to-one parity with the dollar has to be guaranteed somehow — otherwise they’re just another volatile cryptocurrency on the market. Some rely on algorithmic means to maintain the balance, while others promise they have enough fiat reserves to back the currency. In both cases, recent spikes in attempts to cash out have not gone well and cast legitimate doubt about stablecoins’ ability to maintain their value under strain. This has caused more people to attempt abandoning what looked more and more like a sinking ship — increasing the pressure on the stablecoins and making the problem worse. Dollar parity was lost. The panic spread. Exchange rates for all cryptocurrencies were affected, and other companies got dragged down as well. Earlier this year, Celsius, a company that acted as a commercial bank for cryptocurrencies, had to freeze withdrawals and eventually filed for bankruptcy [1] In addition to facing liquidity issues due to customers withdrawing their funds, Celsius had invested a lot of its Ether in a derived product (“sETH“) allowing them to pre-stake money in Ethereum’s future proof-of-stake validation scheme (see part II). Unfortunately, the switch to proof-of-stake keeps being delayed by Ethereum developers, sETH are loosing their value, and the pre-staked ETH remain essentially locked, worsening the solvency problems of Celsius.. Shortly afterward another crypto-bank, Babel, also suspended withdrawals due to liquidity problems. The exact same thing has taken place in recent weeks after rumors that FTX might not be solvent surfaced. Doubling down on the already high levels of irony, the ecosystem created to “free the masses from banks” is experiencing bank-run after bank-run.

Cryptocurrencies are exposed to inflation

The reasons why so many people have been trying to cash out in the last few months, leading to this crash, are worth looking into. Most observers agree that the root cause is inflation [2] Another reason is the fact that due to the prices of energy skyrocketing and exchange rates plummeting, mining is less and less profitable., currently affecting most real-world economies. Investors become more risk averse in the context of a downturn and individuals need to tighten their belts — depriving the ecosystem of the influx of newcomers it depends on, and taking capital out of the ecosystem.

This is noteworthy because one of the main arguments heard in favor of cryptocurrencies is how they can be used as a refuge against inflation and other currency manipulation from governments. After all, monetary creation in cryptocurrencies is set in stone: for instance, the overall supply of Bitcoins will gradually increase until it reaches 21 million, and then stagnate forever. Cryptocurrency enthusiasts are usually quick to point the finger at quantitative easing (QE) as a cause for inflation and proof that governments should not be trusted with currency. It’s actually the other way around: the crypto-market flourished for as long as QE policies flooded investors with free cash. But now that the party’s over everyone’s rushing for the exit.

We already knew that, contrary to early cryptocurrency design goals, government decisions had an impact on the cryptocurrency world — like when China banned mining on its territory. Today it’s also obvious that it’s not as decoupled from the real-world economy as its proponents would have wanted.

Bitcoin has experienced long periods of high inflation in the past despite its slowly-increasing supply. This reveals how it is impacted by external factors its algorithmic governance cannot correct. Source

The absurdity of apolitical money

While part I of this series focused on the notion that cryptocurrencies are not proper currencies at all, a blind spot that remains to be addressed is the notion that they could one day be improved enough to serve this purpose. Many enthusiasts are acutely aware of the flaws in existing blockchain technologies, but remain adamant that future breakthroughs will solve everything. They’re wrong, not because mankind’s ability for engineering is limited, but because the idea is doomed from the outset.

Historically, managing money has always been the prerogative of states. Visigoth law in the 7th century allowed the use of torture to investigate money counterfeiting (in the end the guilty party would have a hand cut off). In the Carolingian Empire (AD 750-900), such crimes were punished “by fire and by death”, while 15th century Brittany opted for boiling and hanging (in that order). Approaching modern day, counterfeiters were still sentenced to death in France — right up until capital punishment was abolished in 1981. And today, we live in a world where the homeless get three to six years in jail for attempting to buy food with fake $20 bills. The message — still — is clear: don’t ever mess with money.

This is a lesson that Facebook, a company that arguably gets away with a lot, learned the hard way when it attempted to launch its own stablecoin. The idea was for big tech companies (including Uber, Lyft, Spotify, PayPal and MasterCard) to create their own universal currency for the digital realm. But, faced with regulatory pushback from US authorities, they had to give up on the project [3] Interestingly, Cambridge Analytica, the infamous company known for harvesting data from 87 million Facebook users and using it to deliver very targeted ads to voters on the social network, also considered launching its own digital currency. Its project was described as “a means of being able to basically inflict government control and private corporate control over individuals, which just takes the whole initial premise of this technology and turns it on its head in this very dystopian way”. and sell all intellectual property and assets. Governments immediately recognized this attempt as a challenge of their power, so nipped it in the bud.

When tech firms attempt to release their own coin, they tend to miss a key aspect of money: currency does not exist in a vacuum as one of many interchangeable means of exchange, but is part of a broader economic system that is deeply integrated with the fabric of our societies. Maintaining a stable economy is widely regarded as one of the main roles states are supposed to fulfill. And when they fail you can expect dramatic plot twists. The Great Depression of 1930 is considered to be a major factor that led to World War II. In 1788 and 1789, right before the French Revolution, two successive years of bad crops resulted in a loaf of bread costing 88% of an average worker’s wages (it didn’t end well for the folks in charge).

Currency should be regarded as part of the toolbox that states can leverage when the greater good is at stake. Central banks can and should devaluate or revaluate currency, and even print more depending on the context. Why? Because otherwise, people die. Arguing that this power should be in the hands of self-interested, private actors (or not exist at all) requires nothing short of blind faith in the stabilizing effects of deregulated capitalism. It is the digital equivalent of saying that we want the people responsible for the subprime crisis to take over the Federal Reserve. If you want a less dramatic example, look no further than the Eurozone: member states have adopted a global currency controlled by the European Central Bank, to which they essentially relinquished monetary policymaking. Now deprived of the tools described above, individual states of the Union have struggled to withstand recent financial crises. Experts agree this was a terrible idea [4] This statement should not be interpreted as fundamental opposition to a union among European people from my part, on the contrary. My position is simply that the way it was implemented has important shortcomings, in particular where the euro is concerned. For the record, I also don’t believe that it would be realistic to go back at this point..

The debatable use of devaluation or quantitative easing by states is often used as an argument as to why people should trust cryptocurrencies. There’s no denying that these tools have been used incompetently on numerous occasions, but that’s hardly a good reason to argue that they should never be used again. Money is so integral to statecraft, it can only be political — and an essential aspect of politics is its conflictual nature. Politics exists because people disagree on things, including how to manage money. Cryptocurrency’s premise that algorithms should be implemented to solve those disagreements is a symptom of a widespread and worrying belief in the tech space that we can find technological solutions to political problems. Our industry’s stellar rise to power has afflicted many computer scientists with the delusion that their understanding of the computers modern society runs on translates into an ability to understand the problems of society itself [5] Our blissful ignorance of the most basic economic and diplomatic principles is perhaps best illustrated by this interview, in which an advisor at Blockchain Capital LLC argues that using Bitcoin as a global currency would prevent wars, because borrowing money would be so impractical states wouldn’t be able to fund long and unpopular conflicts.. This couldn’t be more wrong:

- The algorithms devised so far have unequivocally failed to fix anything — as parts I and II of this series demonstrated.

- Any algorithm proposed in the future will be shot down as soon as it rises in prevalence, since states have an existential need to safeguard their control over their currencies.

- Algorithms were never the right approach to monetary policy in the first place, as this policy should always result from social consensus and be re-evaluated on a periodic basis. As such, it resides purely in the political realm.

Worse, the idea that management by algorithms would be impartial and therefore fairer is also fallacious. There’s no such thing as a neutral algorithm; there are only algorithms with hardcoded politics [6] The idea that cryptocurrencies are neutral technologies and that their built-in transparency is a strong incentive against bad behavior comes up a lot in discussions on the subject. It’s not only false (anyone paying attention is aware of the countless scams and market manipulations plaguing the ecosystem), it also ignores how technological breakthroughs restructure society in ways that are absolutely not neutral (e.g., the printing press, the steam engine, computing, the internet, etc.)..

The politics of cryptocurrencies

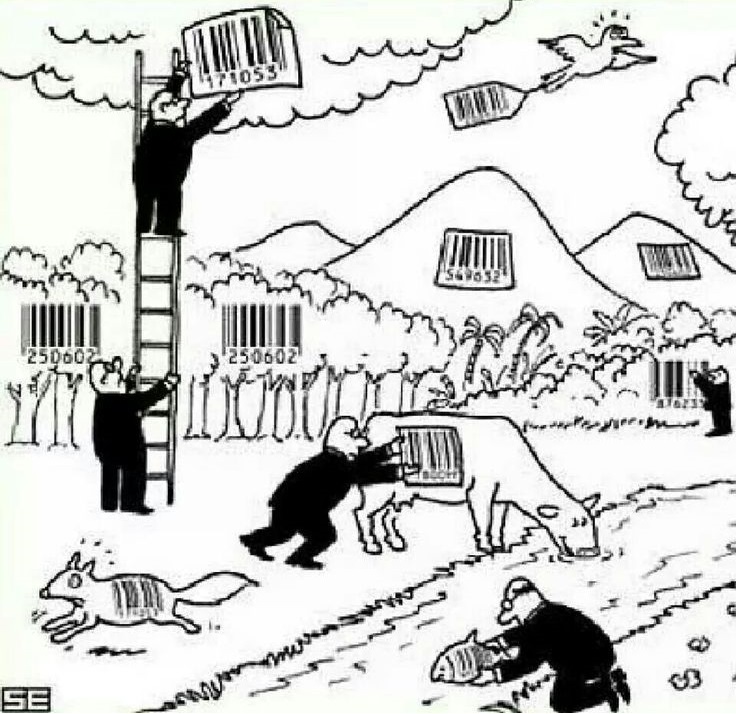

We must therefore examine what political beliefs are embedded in blockchain and cryptocurrency technologies, as this will enlighten us on the risks of widespread adoption. If code is law, which law?

The (g)old standard

One of the most crucial aspects of how the biggest cryptocurrencies are designed is related to money supply. Bitcoin, as mentioned previously, contains a hardcoded limit of 21 million coins. Ethereum has no upper limit, but still controls monetary creation by ensuring no more than 18 million ETH can appear each year [7] Ethereum further fosters deflation by destroying coins paid as gas fees. Constantly deleting money from the pool prevents the supply growing too much.. Bitcoin’s original whitepaper explicitly states that “once a predetermined number of coins have entered circulation, the incentive can transition entirely to transaction fees and be completely inflation free”, evidencing resistance to inflation as a key design goal. Never mind the contradiction of having ended up with a financial instrument known for its unpredictable inflationary and deflationary spirals, while still promoting it as a safeguard against either.

Even though we debunked this purported resistance to inflation in a previous section, it remains a major element of the pro-Bitcoin discourse to this day. It’s no surprise that Bitcoin has been called “digital gold” in the past, or that its own vernacular contains terms like “mining”, as the theoretical foundations of the cryptocurrency are tightly linked to the idea of the gold standard. At various times during the 20th century, fiat currencies were tied to a physical resource (that is, gold or silver), and the state could not issue more currency than it would be able to back with metal. To print extra money, they had to dig up more gold first, but the world’s supply is limited [8] If the U.S. were to go back to the gold standard, it would need to purchase half the world’s gold to back its own economy. There isn’t enough gold on Earth for all countries to go back to the gold standard.. In 1972, the US gave up on that system forever for many reasons — including the fact that it constrained the government too much and prevented expansionary policies when they were warranted.

Today, the consensus against the gold standard is quasi-unanimous. Only a few right-wing think tanks such as the CATO Institute (funded by Charles Koch and Murray Rothbard) and hardcore Republicans like Ron Paul still defend it. It’s therefore surprising to see the gold standard used as a foundation in major cryptocurrencies, then defended as sound economic policy by crypto enthusiasts.

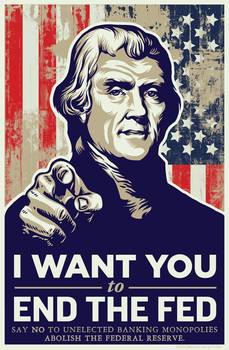

Abolish the Fed!

Another central idea to the construction of cryptocurrencies is that their decentralized character allows them to operate without the supervision of trusted parties. Again, we can quote Satoshi Nakamoto’s original whitepaper: “the root problem with conventional currency is all the trust that’s required to make it work. The central bank must be trusted not to debase the currency, but the history of fiat currencies is full of breaches of that trust”. The point of this paragraph is not to examine the validity of this rejection of central banks, but to recognize it for what it is: a profoundly right-wing idea. Perfect examples of this thinking can be found in an article titled “Your Central Bank Steals Your Money“, or the comments section of any online content critical of blockchain technology. FTX founder Sam Bankman-Fried accused the Fed of being responsible for the current downturn [9] Arguments claiming that central banks cause uncontrollable inflation by manipulating interest rates fail to account for the fact that these actions are actually taken in response to inflation, in order to manage it. In normal conditions, central banks usually target a 2% inflation rate that orthodox economists believe to be the most auspicious. (although recent events have cast doubt regarding Bankman-Fried’s economic expertise). At its worst, the cryptocurrency ecosystem dips into antisemitism and alt-right conspiracy theories involving shadowy elite figures and the deep-state colluding to steal from the middle-class.

The idea of running the economy without central banks has long been a pillar of libertarian thinking

None of this ideology was born with cryptocurrencies. Looking at Federal Reserve detractors outside this sphere, we easily find libertarian economists (Charles Hugh Smith went on the record about his nostalgia for the gold standard) and more right-wing think tanks. This is also a recurring theme for pundits like Alex Jones.

Libertarians and anarcho-capitalists

Even if the blockchain technology were apolitical, the people who have defended its axioms for decades certainly seem to share a common vision. The personalities listed previously can be associated with the American libertarian movement [10] Also referred to as “anarcho-capitalism”, although traditional anarchist schools of thought reject any affiliation with it due to irreconcilable ideological differences.. The centerpiece of their philosophy is the idea of freedom as a rejection of the state’s tyranny. States, they argue, impose impermissible limits on individual liberties and need to be constrained to their smallest possible form: one which safeguards private property and nothing more. In particular, they perceive any attempt to redistribute wealth or regulate the economy and free trade as an unacceptable invasion into the private lives of citizens.

HateWatch documented the enthusiasm and involvement of far-right extremists in the early days of Bitcoin

I’m not saying that all cryptocurrency users would identify themselves as libertarians; however, it’s hard to dispute that the way that blockchains were designed perfectly embraces libertarian ideals. It’s also obvious that the cryptocurrency ecosystem has been a major factor in bringing what used to be marginal economic theories to the forefront of public debate. Without falling into childish moral judgments like “right-wing equals bad”, imagining a society transformed by cryptocurrencies can only be achieved through a critique of libertarianism’s political philosophy. Thankfully, greater minds have already taken up this task for us. Due to my personal leanings, I will provide Noam Chomsky’s account — he identifies as a libertarian socialist [11] Just like anarcho-capitalism has little to do with anarchism, libertarian-socialism is significantly different from libertarianism (but is in fact very close to anarchism). Try to keep up! — but you can pick others from this list if they are more to your liking. Or, if you are aligned with the idea that a Darwinian clash of market forces is what’s best for society, you may simply skip the next few paragraphs.

Libertarians reject the power of the state on the grounds that nobody agrees to a social contract: we are bound to our country’s laws by birth, and never get a chance to reject them. Liberty being their cardinal value implies three things:

- All social interactions should be governed by mutual agreements, freely consented to by interested parties.

- There should not be any constraints on what types of arrangements can be struck, especially not from the state.

- The powers of the state must be as limited as possible, and it should only act as an arbiter that enforces peer-to-peer agreements.

It may sound like a great system among equals, but unfortunately that’s not the world we live in right now since people interact from different positions of wealth and power. If Jeff Bezos wants something from me, it’s very likely he’ll get it — and on his terms. While I’m technically at liberty to refuse, any resistance I put up can easily be defeated because the disproportion of power is so vast. Libertarians don’t consider this to be a problem, but rather a feature of the system: it feels natural to them that the most skilled or business-savvy are rewarded with increased power.

“Taxation is theft”, echoed in some Bitcoin circles, is one of the rallying cries of libertarians. It embodies their deep objection to redistribution mechanisms

The problem is, the set of rules promoted by libertarianism results in a gradual increase in the concentration of power over time. The powerful can leverage their position to obtain an edge over the rest of the field — which then puts them in a slightly better position they can leverage even more. Even if we were to magically reset society to a purely egalitarian state (which is absolutely not part of the libertarian agenda), we’d be back to square one after a few generations. It’s no surprise that this ideology is especially appealing to entities already doing well — like millionaires and multinationals — who want nothing more than to consolidate their power and create an environment where they cannot be challenged anymore. In true Orwellian fashion, the term libertarianism ends up representing the opposite of what it means: its implementation results in subjugation to a corporate tyranny where the private sector effectively holds unlimited, unchecked power.

Interestingly, this assessment isn’t theoretical anymore. The cryptocurrency world was built upon libertarianism’s precepts, and can be seen as their miniature ideal society. Parts I and II of this series demonstrated, hopefully, how the resulting dynamics indeed concentrated power in the hands of the already very wealthy. The one thing left to do now is conclude that this was the underlying structure’s design instead of an unfortunate side-effect.

The future

I wouldn’t care too much about libertarians living out their own little dystopia if there wasn’t a significant risk it could contaminate the internet as a whole. Although I don’t believe that cryptocurrencies will become mainstream anytime soon [12] At least not in their current form. CBDCs however have great potential for widespread adoption but they’re a very much a different beast so they won’t be covered here., other new blockchain-based technologies are still being tested and deployed.

Web3

One such technology is called Web3, and despite still being fuzzy, it represents a new iteration of the overall concept of the internet. The core premise also revolves around decentralization: internet services today mostly revolve around a handful of platforms like Google, Amazon, Microsoft and Facebook, whose leadership, if not contested in meaningful ways, is at least criticized by many. The idea behind Web3 is that user data, currently hoarded by these companies, will in the future be stored on the blockchain where it can be decentralized again.

Online payments will take place in Ether without the need for third-party processors like PayPal or Stripe, and wallets will be integrated into browsers directly. We’ll resolve domain names by looking them up on the blockchain. Access control will rely on NFTs and smart contracts. You get the idea.

The elephant in the room is whether the very inefficient blockchain technology can sustain the weight of the whole internet. In addition to the prohibitive expensiveness of any blockchain operation, plus other issues mentioned already, a significant roadblock is the ability for the general public to interact with the blockchain. Assuming all the world’s data were migrated there somehow, how would you, as a user or a website owner, access it? Blockchains are supposed to be distributed and decentralized, so surely you can get a copy of the data. Indeed, it’s easy to do so… provided you have enough storage space. The Ethereum blockchain currently weighs 875 GB — a number that can only go up. Granted, you may not need a full copy, but even storing the latest 10% of this single blockchain is impractical in most cases, and absolutely unthinkable for mobile devices.

To circumvent this problem, a few companies, like Infura or OpenSea, have developed interfaces (that is, APIs) that programmers can query to access the state of the blockchain or blockchain-backed objects like NFTs. This way, you don’t need a copy of the data anymore. You can instead ask a trusted party whatever you’re interested in, and they’ll look it up on the blockchain for you and send back the result. What’s that I just said? “Trusted party”? Oh yes. The task of extracting information from the blockchain is so tedious that it was offloaded to a couple of companies who have become the de facto authorities of what it contains. Virtually all blockchain-related websites rely on these services under the hood. It doesn’t matter that the actual information is immutable and distributed if single-points-of-failure control all the world’s representations of this data. Censorship resistance was the last pro-blockchain argument we hadn’t addressed so far, but it doesn’t hold water either. In fact, the ecosystem relies on this to police itself, for instance when OpenSea [13] A platform which holds 97% of the NFT market which, I’m assured, is still decentralized. delists stolen NFTs to prevent their resale. This power has been abused unilaterally too. One way or another, the blockchain world keeps recreating the exact structures it promises to topple.

No matter what the caption says, many entities represented in the Web3 column are companies, not protocols. The objective of Web3 is less decentralization than a changing of the guard

I have serious doubts that Web3 is ever going to see the light of day. If anything, we’ve learned so far that blockchains never scale well enough to properly handle real-world applications, yet Web3 has ambitions covering the whole internet. Another important hurdle Web3 will have to face is that making everything public on the blockchain is going against the times. The last decade has been defined by successions of debates on the proper handling of user data. A lot of the criticism revolved around profiles or pictures being made public by default, and several countries passed corresponding legislation. Please get in touch with me if you can explain how personal information stored on the blockchain can ever comply with GDPR‘s provision against its transfer outside the EU. Some (like Dan Olson in his great video on the subject) have framed this new paradigm as an attempt by a new wave of tech start-ups to usurp the existing giants’ throne by contesting their exclusive control of our personal information. And this may be the biggest obstacle to Web3 ever taking off: the current big players have no intention of playing ball.

Third Life

The thing is, those big players have their own vision of what the brave new world should look like, and they’re at the center of it. Microsoft has unveiled its metaverse strategy. Facebook went so far as changing its name to “Meta” — a move, we’re asked to believe, that’s solely motivated by its sincere belief in the metaverse’s viability as a concept, and nothing to do with its initial brand having become more radioactive than Fukushima sushi.

The best way to explain the concept of a metaverse is to use the 2018 movie “Ready Player One” as a reference. Even if you haven’t seen it, the trailer should explain more than most articles out there. A metaverse is a parallel world accessed through a virtual reality (VR) headset, but beyond the hardware aspect it’s basically Second Life. It’s an extension of the physical space where you’ll be able to move around, hang out with friends, maybe even work. I know what you’re thinking: what would be the point? We can already do all this in real life. Yet we cannot dismiss the idea of the metaverse on those grounds alone: when the internet was introduced, people were famously skeptical. They didn’t get it: mail could already be sent in paper form, newspapers contained all the information you ever wanted, and the idea that you’d order products from online stores without seeing them first felt ludicrous. Yet 30 years later, here we are, because it’s the modes of production that define consumer needs — not the other way around. If all social interactions move there, we’ll want the metaverse. Tech enthusiasts describe it as nothing short of a new revolution on the same scale as the internet.

Metaverse and the (absence of) blockchain

But before we ask ourselves whether the metaverse has a chance of ever affecting our lives, we need to clarify one additional thing. What does it have to do with blockchains? Back in 2002, Second Life managed to achieve some level of success with both its virtual world and homemade currency without relying on any of the technologies described in this series. However, with the current concept we’ll be offered different metaverses — worlds operated by various actors that you’ll teleport to and from like neighboring islands. For the overall experience to be consistent, information needs to be shared across all metaverses. If you purchase genuine Nike shoes for your avatar in Microsoft’s realm, you certainly don’t expect to walk around barefoot when you move to Facebook’s. The solution to this, according to some, is that all “ownable” objects in the metaverse should be represented as NFTs, making the blockchain a sort of interoperability mechanism across digital worlds.

It is however very curious that no matter how much Microsoft and Facebook are hyping the metaverse concept at the moment, they hardly ever mention the blockchain. Even though they’ve created a consortium called the Metaverse Standards Forum with Adobe, Nvidia, Alibaba and many others, a quick glance at the members reveals that blockchain actors are not even involved. This tells me that no matter what the crypto industry believes, big tech has plans to move on its own. The truth is, there’s a much more obvious solution to the multi-metaverse problem: having a clear hegemon emerge. The major players in the metaverse-space don’t talk about blockchains because currently interoperability is only plan B. They’d much rather kill the competition and only have one giant island (theirs) used by everyone in the world. If history is any indication, “openness” has a much better chance of being used cynically and strategically to gain traction until such a time that it becomes the right move to lock users in.

Why I worry about the metaverse

Ironically, the concept of metaverses worried me less when I was persuaded they too would be brought down by the Midas touch of blockchains — a technology which, let me remind you, has never led to a single practical application to this day due to its inherent limitations. Taking blockchains out of metaverses doesn’t change the fact that both share the same libertarian-at-heart ideological foundation; and in the case of the latter, their inevitable degeneration into corporate tyranny feels even more obvious [14] Funnily, part of Ready Player One’s plot revolves around wresting control of the metaverse away from its parent company!. Some thinkers call this specific brand of subjection “techno-feudalism“. After all the controversies about how social media might be destroying the world’s social fabric, do we really want to spend half our lives in digital realms managed by entities that have consistently failed us?

We may not have a choice. The companies investing heavily in the metaverse right now are some of the most powerful in the world. They may have the ability (through dominant positions or sheer marketing might) to force-feed us whatever new paradigm benefits them. At the moment, we’re protected by the high price of VR headsets, but this may not last forever. I fear that in 20 years time, there’ll be strong incentives to have one in every home and that resistance to the metaverse will come at the cost of social isolation.

I’ll wrap up this section by providing the reason why I think tech companies have an existential reason to fight this battle fiercely: the fact that late-stage capitalism is facing a structural problem. The system demands growth, and in fact can only survive if it keeps growing, but there is a ceiling — growth has to stop at some point. Not for moral reasons, but simply because eventually our planet will run out of resources. The saying that “there cannot be infinite growth in a finite world” is often used to advocate for degrowth and moving away from capitalism altogether. Capitalism’s genius answer is to sidestep reality and create new worlds, virtual and infinite this time, where value can be extracted forevermore [15] This also explains why many billionaires are so excited about space exploration and the prospect of colonizing new planets..

Looking at metaverses from this angle allows us to understand why they’ll primarily be designed as marketplaces — where all real-life goods can be duplicated and sold again, and with multinationals acting as almighty landlords. The end-goal is the commodification of every single aspect of our lives. I, for one, want no part of it.

Conclusion

It would be easy to blame blockchains for all their failings and call it a day. The applications they’ve brought us (or still hope to bring) are absurd. Everything is wrong with them. Best case scenario, they’re absolutely useless. More often than not, they wreck our planet and enable whole new forms of oppression. Yet the quasi-religious zeal they often inspire tells us something else. The blockchain dream carries with it the promise of a fairer society, along with a hint of revenge toward the finance world that’s ruined people’s lives time and again. We shouldn’t be surprised that it’s hard to let it go.

What really makes me mad is how exploitative the alternative turned out to be. Read these testimonies of people who lost everything and see if it doesn’t break your heart. It’s not about making questionable financial placements; it’s about modern society leaving many people behind with no hope of bettering their lives beyond means they deep-down know is gambling. And then those means turn out to be yet another secret tool for transferring wealth from the disenfranchised to the rich.

It’s only in the very last paragraph of this series that we finally find the first utility ever generated by blockchains, cryptocurrencies and NFTs. It’s not what they are, it’s what they reveal about the state of the world and the intolerable inequality people have to endure. About what society may become soon unless we do something about it. Beyond this, dear reader, wherever you are, if you’re trying to rise up out of misery, I genuinely hope you make it. But blockchains are not the way.