Just breathe! Unusual biometrics based on odor | Kaspersky official blog

Credit to Author: Enoch Root| Date: Mon, 18 Jul 2022 12:00:02 +0000

A group of researchers from several Japanese universities recently published an interesting study describing a completely new form of biometric authentication: breath analysis. The idea is similar to the breath alcohol tests that ordinary drivers like you and me are sometimes subjected to, and which professional drivers and people in other hazardous occupations undergo on a regular basis.

However, the similarity ends there. The method proposed in the study is much more complicated. For a start, it has to identify not one but several different chemical compounds in the breath. And what’s more, the procedure needs not only to determine the concentration of certain substances, but to also distinguish one person from another by their chemical “breathprint”.

But…why?

The neat thing about the work of these academic researchers is that they don’t have to set themselves any practical goals! That is, they’re doing it simply because they can.

Overall, breath analysis is considered to be a cutting-edge area of research. With the help of machine learning to process data, serious breakthroughs have been made in this area — for example, in the diagnosis of respiratory diseases. So if the systems of analysis and learning algorithms are already available, why not investigate the possibility of authentication?

How does odor-based authentication work?

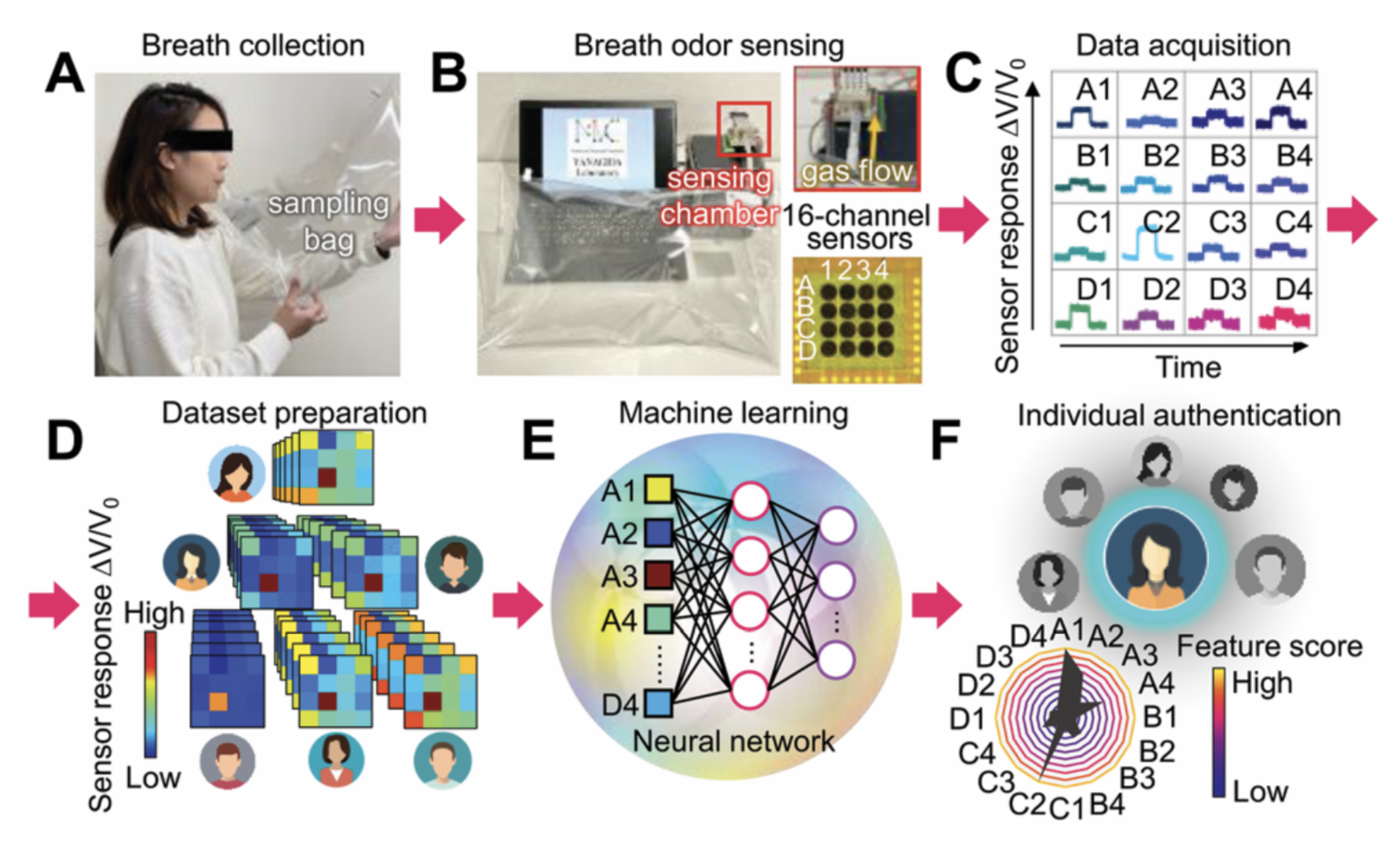

At the first stage, test subjects’ exhaled air is collected. Then, that air is passed through a 16-channel analyzer (the researchers tried collecting data through a fewer number of sensors, but this immediately reduced the method’s effectiveness).

Each channel separately detects a certain chemical compound in the air. The analyzer records not only the intensity of the signal from the sensors, but also how that intensity changes over time.

This is how the breath-based authentication system works at this stage Source

As a result, quite a large array of data is collected, which is then processed with the help of a machine-learning algorithm. After being trained on the test data, the algorithm can fairly accurately identify a person by their breath.

How reliable is it?

The Japanese scientists were able to accurately identify a person by their breath in 97% of cases. Can that be deemed a success? There’s not enough data in this study to fully answer that question.

We can compare the overall performance with data from a 2016 study, which, among other things, investigated the features of the assessment of biometric systems. On the surface, the breath method is just as reliable as common fingerprint scanners, and even slightly outperforms face recognition technologies.

Accuracy of various biometric authentication technologies. Source

However, as emphasized in the above-mentioned 2016 study, it’s important to take into account the ratio of false negatives (failing to recognize registered users) to false positives (authenticating a stranger). We meet the problem of false negatives every day when our smartphones don’t recognize us — albeit not the gravest of problems. False positives, on the other hand, are unpleasant, so eliminating them is a top priority. That said, there’s not enough detailed information in this study about how odor-based authentication is doing on this front.

On an interesting side note, the breath analysis researchers also referenced previous studies — including their own — and recorded the progress, for example, in comparison with the chemical analysis of human sweat. (Yes, sweat-based authentication has also been researched!)

How practical is it?

The researchers used expensive lab equipment that you can’t just attach to a laptop, phone, or even a car. Though these days it’s possible to equip a car with a lock that blocks the car’s ignition if alcohol is detected in the air, the equipment required for breath-based authentication is significantly more sophisticated and expensive.

Besides, when reading the study in more detail, your come across even more reasons why we won’t all be breathing into our smartphones to unlock them in the foreseeable future: as already mentioned, to increase accuracy, they also measured the decay time of certain chemical compounds — which took as long as 40 minutes!

And that’s not all: the test subjects were not allowed to eat for six hours before the experiment. The authors note that the accuracy of the results can be influenced by a recent dinner, as well as the compounds found in the breath that accompany a range of illnesses. Seems like the light aroma of alcohol or simply a head cold could mess up the test.

To sum up: here and now, there’s not much practical use for this technology. But it’s clearly an interesting area of research which could be developed further in the future — if not in the form of “breathe into this tube” authentication, at least, for example, in improved medical diagnosis systems.