Can you trust digital signatures in PDF files?

Credit to Author: Nikolay Pankov| Date: Tue, 14 Jan 2020 12:31:34 +0000

Hardly a company or government agency exists that does not use PDF files. And they often use digital signatures to ensure the authenticity of such documents. When you open a signed file in any PDF viewer, the program displays a flag indicating that the document is signed, and by whom, and gives you access to the signature validation menu.

So, a team of researchers from several German universities set out to test the robustness of PDF signatures. Vladislav Mladenov from Ruhr-Universität Bochum shared the team’s findings at the Chaos Communication Congress (36С3).

The researchers’ task was simple: Modify the contents of a signed PDF document without invalidating the signature in the process. In theory, cybercriminals could do the same to impart false information or add malicious content to a signed file. After all, clients who receive a signed document from a bank are likely to trust it and click on any links in it.

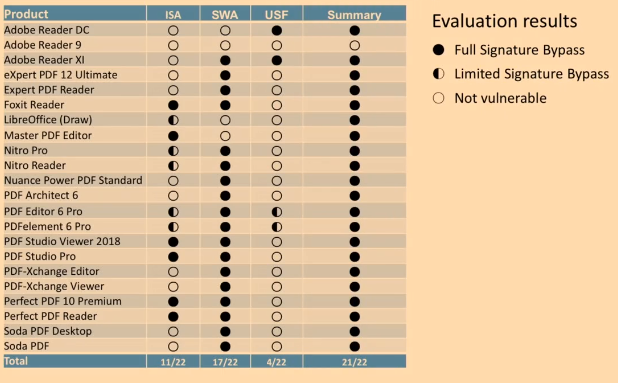

The team selected 22 popular PDF viewers for various platforms, and systematically fed them the results of their experiments.

PDF file structure

First, a few words about the PDF format. Each file consists of four main parts: the header, which shows the PDF version; the body, which shows the main content seen by the user; the Xref section, a directory listing the objects inside the body and their locations (for displaying the content); and the trailer, with which PDF viewers start to read the document. The trailer contains two important parameters that tell the program where to start processing the file, and where the Xref section begins.

Integrated in the format is an incremental update function that allows the user to, for example, highlight part of the text and leave comments. From a technical point of view, the function adds three more sections: updates for the body, a new Xref directory, and a new trailer. That effectively makes it possible to change how the objects are seen by the user, and to add new content. In essence, a digital signature is also an incremental update, adding another element and corresponding sections to the file.

Incremental saving attack (ISA)

First, the team tried to add extra sections to the file with another incremental update using a text editor. Strictly speaking, that’s not an attack — the team simply used a function implemented by the creators of the format. When a user opens a file that’s been modified in this way, the PDF reader usually displays a message saying that the digital signature is valid but the document has been modified. Not the most enlightening message, especially not for an inexperienced user. Worse, one of the PDF viewers (LibreOffice) did not even show the message.

The next experiment involved removing the two final sections (that is, adding an update to the body, but not the new Xref and trailer). Some applications refused to work with such a file. Two PDF viewers saw that the sections were missing and automatically added them without notifying the reader about a change in content. Three others swallowed the file without any objection.

Next, the researchers wondered what would happen if they simply copied the digital signature into their own “manual” update. Two more viewers fell for it — Foxit and MasterPDF.

In total, 11 of the 22 PDF viewers proved vulnerable to these simple manipulations. What’s more, six of them showed absolutely no signs that the document opened for viewing had been modified. In the other five cases, to reveal any sign of manipulation, the user had to enter the menu and check the validity of the digital signature manually; simply opening the file was insufficient.

Signature wrapping attack (SWA)

Signing a document adds two important fields as an incremental update to the body: /Contents, which contains the signature, and /ByteRange, which describes exactly what was signed. In the latter are four parameters — defining the start of the file, the number of bytes before the signature code, a byte determining where the signature code ends, and the number of bytes after the signature — because the digital signature is a sequence of characters generated by cryptographic means from the code of the PDF document. Naturally, the signature cannot sign itself, so the area where it is stored is excluded from the process of signature calculation.

The researchers attempted to add another /ByteRange field immediately after the signature. The first two values in it remained unchanged, only the address of the end of the signature code was altered. The result was the appearance of an additional space in the file allowing any malicious objects to be added, as well as the Xref section describing them. In theory, if the file were read correctly, the PDF viewer would simply not get as far as this section. However, 17 of the 22 applications were vulnerable to such an attack.

Universal signature forgery (USF)

For good measure, the research team also decided to stress-test the applications against a standard pentesting trick whereby an attempt is made to replace the values of fields with incorrect ones or simply delete them. When experimenting with the /Contents section, it turned out that if the real signature were replaced with the value 0x00, two viewers still validated it.

And what if the signature were left in place, but the /ByteRange section (that is, information about what exactly was signed) were deleted? Or a null were inserted instead of real values? In both cases, some viewers validated such a signature.

In total, 4 of the 22 programs were found to contain implementation errors that could be exploited.

The summary results table shows that no fewer than 21 of the 22 PDF viewers could be hoodwinked. That is, for all but one of them, it is possible to create a PDF file with malicious content or false information that looks valid to the user.

Summary table of vulnerabilities of PDF viewers. Source

Funnily enough, the one application that did not fall for any of the researchers’ tricks was Adobe Reader 9. The problem is that it is susceptible to an RCE vulnerability, and it is used by Linux users only, simply because it is the latest version available to them.

Practical conclusions

What practical conclusion can we draw from all of that? First, no one should blindly trust PDF digital signatures. If you see a green checkmark somewhere, that does not necessarily mean the signature is valid.

Second, even a signed document can pose a risk. So before opening any files received online, or clicking any links in them, make sure you have a reliable security solution installed on your computer.