The WannaCry hangover

Credit to Author: Andrew Brandt| Date: Wed, 18 Sep 2019 10:01:25 +0000

This morning, SophosLabs is releasing a deep dive into the aftermath of a malware that, two years ago, looked like an unstoppable scourge. On the morning of May 12, 2017, organizations and individuals around the world were attacked by malware now known as WannaCry.

WannaCry’s rapid spread, enabled by its implementation of a Windows vulnerability stolen from an intelligence agency, was suddenly halted when security researchers registered an internet domain name embedded in the code – a routine research procedure that, inadvertently, tripped a “kill switch” subroutine in the malware, causing it to stop infecting computers. A small number of variants released in the following days, using new kill switch domains, were shut down using the same method.

Prior to the malware’s first appearance, Microsoft released an update to close off the vulnerability to exploitation, which would have prevented the infection from spreading. The delay in installing that April, 2017 update directly contributed to WannaCry’s ability to copy itself from computer to computer.

By the time the kill switch domain had any effect, the malware had already wrought a lot of destruction. But the kill switch, surprisingly, didn’t mean an end to WannaCry, even though (as far as we know) WannaCry was updated and rereleased only twice a few days after the first infection. In fact, WannaCry detections appear to be at an all-time high, surpassing the number of detections of older worm malware such as Conficker. The malware continues to infect computers worldwide.

WannaCry never went away, it just got more broken

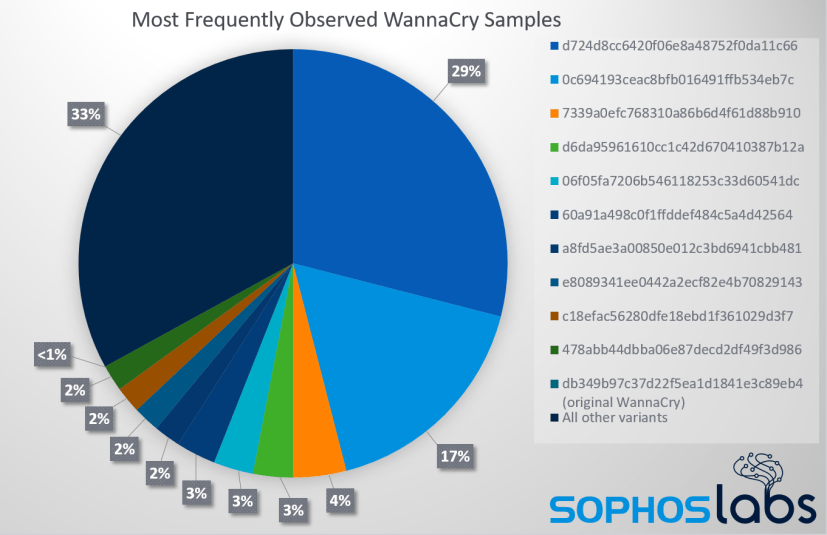

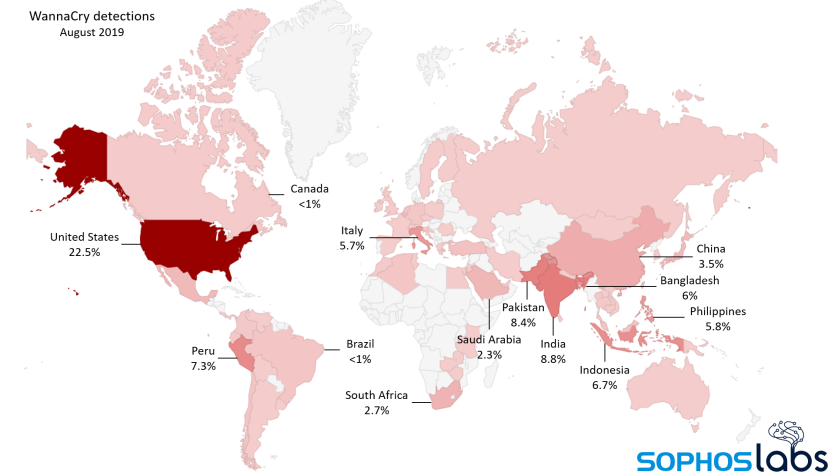

So why isn’t the world still up in arms about WannaCry? It turns out, someone (or possibly several someones) tinkered with WannaCry at some point after the initial attack, and those modified versions are what’s triggering nearly all the detections we now see. Where there was once just a single, unique WannaCry binary, there are now more than 12,000 variants in circulation. In just the month of August, 2019, Sophos detected, and blocked, more than 4.3 million attempts by infected computers to spread some version of WannaCry to a protected endpoint.

The one upside: Virtually all the WannaCry variants we’ve discovered are catastrophically broken, incapable of encrypting the computers of its victims. But these variants are still quite capable of spreading broken copies of themselves to Windows computers that haven’t been patched to fix the bug that allowed WannaCry to spread so quickly in the first place.

The original kill switch domains have remained active since May, 2017, when security researchers registered the domains, effectively ending the WannaCry attack. To analyze why WannaCry still seems to be spreading, despite the fact that the kill switch is still active, we looked at about a fifth of the variants that we detected between September and December, 2018.

In that three month period a year ago, we detected 5.1 million failed attempts by WannaCry-infected computers to infect a customer’s protected machine or machines. Out of that sample set, we made some interesting discoveries:

- All of the 2,725 variants of WannaCry we analyzed contained some form of a bypass for the kill switch code that stymied the original WannaCry.

- Ten unique, modified versions of WannaCry malware accounted for 3.4 million (66.7%) of the detections, with the top three accounting for 2.6 million (50.1%).

- 476 of the unique files (3.8%) accounted for an overwhelming 98.8% of the detections.

- 12,005 of the unique files identified (96.1%) were seen fewer than 100 times each.

- The original, true WannaCry binary, with an uncorrupted payload capable of encrypting a victim’s computer, was seen only 40 times – a number so low that it could easily be attributed to security researchers or analysts conducting tests, rather than a real attack.

- Sophos’ original WannaCry behavioral definition, CXmal-Wanna-A, offers effective defense against any attempted infections.

The most consequential modification to these latter-day WannaCry variants is the kill switch bypass. We detected four different methods, some more kludgy than others, that had been used to get around the protection the kill switch subroutine provides.

Deferring patches isn’t optional, anymore

WannaCry’s spread was, and still is, aided by the fact that large organizations tend to defer installing Windows update patches, out of an abundance of caution, because some updates have, historically, caused incompatibilities with third party software. This debate over whether to update right away or to defer the updates until testing can be completed continues even to this day, with some tech columnists persisting in advising users not to install patches right away as a method of mitigating the consequences of an occasional patch that doesn’t work as intended.

While there are limited circumstances in which some specific groups of users will not want a computer to download and install operating system updates, nearly all people and organizations do not fall into this category. Unfortunately, people who spread information about how to defer or avoid updates rarely discuss the more nuanced reasons why someone might want (or not want) to disable this feature. There are tradeoffs and serious consequences to not installing updates. But some IT administrators’ or individuals’ reticence to install updates appears to be deep-seated and widespread, despite the risk such inaction poses.

The continuous rise in WannaCry detections does raise warning flags: it means there are still machines whose owners have not installed an operating system update in more than two years, and those machines are vulnerable not only to WannaCry, but to much more dangerous types of attack that have emerged in the past two years.

And this leads to an inescapable point: The fact remains that, if the original kill switch domains were to suddenly become unregistered, the potent, harmful versions of WannaCry could suddenly become virulent again, distributed by and to a plethora of vulnerable, unpatched machines.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to acknowledge the efforts of many in the security community who helped build an early understanding of the effect and impact of WannaCry, including Marcus Hutchins, Jamie Hankins, and Matt Suiche, and SophosLabs researchers Fraser Howard and Anton Kalinin for their assistance with the research and technical guidance for this report. We will publish IoCs from this report on our Github.