Nuclear Energy Programs Rarely Lead to Nuclear Weapons

Credit to Author: Daniel Oberhaus| Date: Thu, 09 Nov 2017 15:00:00 +0000

A study released on Monday in the journal International Security found that national nuclear energy programs “rarely” lead to the development of nuclear weapons.

This is contrary to a longstanding assumption among nuclear policy advisors and heads of state that the development of nuclear energy and the proliferation of nuclear weapons are closely linked. Last month, President Trump called for tougher sanctions on Iran for violating its landmark 2015 nuclear deal with the US, even though the country’s uranium enrichment program has successfully been scaled back to peaceful uses.

The tendency to link the peaceful use of nuclear energy with its weaponization is clearly persistent, but as demonstrated by this new study, it’s an association without much historical evidence. The majority of countries that have developed nuclear weapons either did so before developing commercial nuclear energy, or in tandem. As noted by the study, “Why Nuclear Energy Rarely Leads to Proliferation,” a country’s pursuit of nuclear energy results in increased international scrutiny of that country and raises the costliness of nonproliferation sanctions, which has the effect of disincentivizing the development of nuclear weapons by that country.

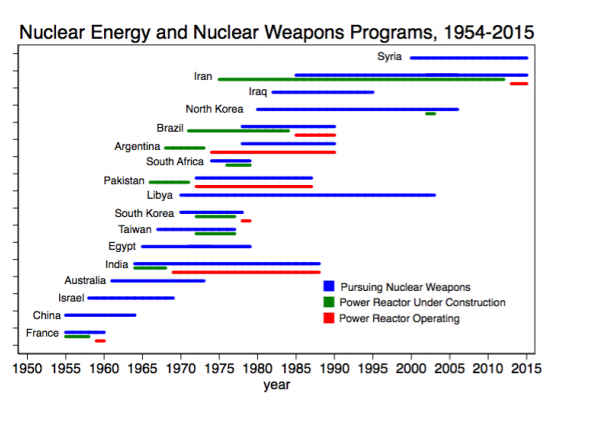

The study’s conclusion is based on a historical analysis of nuclear energy and weapons programs from 1954—the year the first commercial nuclear reactor came online in Russia—through 2000. Only five of more than fifteen countries that have pursued nuclear weapons since 1954 did so after developing a nuclear energy program, namely Argentina, Iran, India, and Pakistan. The other nuclear countries either began by developing a nuclear weapons program, such as China and France, or developed these weapons in tandem with their nuclear energy programs.

Even though the report’s author argues that the link between nuclear power and nuclear weapons has been “overstated,” it’s hard to ignore the reality that nearly a third of all nuclear countries did weaponize civilian nuclear energy programs. All it takes is one nuclear weapon to cause a massive amount of destruction, so the unease about the proliferation of national nuclear power initiatives makes sense.

Historically, however, the very pursuit of these nuclear power programs, and the attendant fears about them, have had the effect of deterring the development of nuclear weapons.

According to the study’s author Nicholas Miller, a nuclear security researcher and assistant professor at Dartmouth College, the reason that nuclear energy programs don’t tend to lead to the development of nuclear weapons has to do with improved international scrutiny and surveillance of such programs, as well as political fears of international sanctions.

“When a country announces it is pursuing nuclear energy, it’s a sign to other nations that maybe they should start paying more attention to what that country is doing,” Miller told me on the phone.

Recent history lends weight to Miller’s observations.

In 2015, the United States brokered a landmark non-proliferation deal with Iran that limited the country’s ability to enrich uranium and plutonium, the main components in nuclear weapons. As part of the deal, the United States would lift the crippling economic sanctions it had imposed on the country.

As Miller told me on the phone, Iran—which has had a nuclear energy program since the mid-1970s—is a clear example of a country that has been using its nuclear energy program as an excuse for weapons research.

Although Iran has claimed that it was only refining uranium for medical research and to expand its nuclear energy program, in 2003 the International Atomic Energy Agency—a nuclear watchdog based in Austria—found traces of highly enriched uranium at facilities in the country that suggested Iran was pursuing nuclear energy for non-peaceful purposes.

Read More: Okay, WTF is Uranium?

After initially agreeing to work with the IAEA to foster transparency, Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad resumed uranium enrichment in the mid-2000s. This resulted in a series of increasingly strict sanctions on Iran by the Bush and Obama administrations, culminating in the 2015 Iran nuclear deal.

In October, President Trump called for ditching this landmark agreement on the basis that Iran is not holding up its end of the deal, and has called for tougher sanctions. This was against the opinion of pretty much every nuclear watch group including the IAEA and the President’s own national security advisors, who aren’t disputing that Iran is upholding its end of the agreement.

Although Iran threatened that it could get its enrichment facilities up and running within a matter of days if Trump withdraws from the agreement, lawmakers are working to preserve the deal and effectively limit the country’s nuclear capacity to peaceful uses.

The success of the Iran deal makes it clear that political and economic deterrents are an effective way to allow nuclear energy programs without nuclear weapons development. Yet the connection between the two has a long history among policy experts.

In one of the earliest reports on international nuclear policy, the 1946 Acheson-Lilienthal report, the authors note that “the industry required and the technology developed for the realization of atomic weapons are the same industry and same technology which play so essential a part in man’s almost universal striving to improve his standard of living and his control of nature.” This same sentiment was echoed by then-Nuclear Regulatory Commissioner Victor Gilinsky in a 1979 report, and in 2009 by the eminent Brazilian physicist José Goldemberg.

Yet with the exception of North Korea, which doesn’t have an energy-generating nuclear power program, sanctions and international monitors have proven to be an effective deterrent to weaponizing civilian nuclear energy programs. The 2015 Iran nuclear deal is merely the most recent example of nuclear deterrence in action. As Miller’s report makes clear, to bar a country from pursuing nuclear energy on the grounds that it will lead to its weaponization is to block a potent path to economic prosperity for developing nations through relatively clean energy.

Read More: Russia Has the World’s Largest Stockpile of Highly Enriched Uranium

Miller’s report is a sobering reminder that politics often ignores actual historical trends. Although nuclear energy is a far from a perfect energy solution, it hasn’t resulted in the nuclear arms race among developing countries that analysts have been predicting for decades.

In some ways, this is a self-fulfilling prophecy: the fear that civilian nuclear energy programs would be weaponized has resulted in policies designed to limit proliferation, and their success is a testament to the effectiveness of these policies. Today, 31 countries rely on nuclear energy to some extent, yet only nine are known to possess nuclear weapons. Clearly it’s possible to have our nuclear energy, and use it peacefully, too.