This Company Wants to ‘Disrupt’ Alcoholism with an App

Credit to Author: Laura Feinstein| Date: Tue, 07 Nov 2017 17:00:00 +0000

“People who use Triggr drink less and get weekly rewards—more fun and cheaper than therapy!” The Facebook ad, a Suggested Post, showed a young woman looking dejectedly at a series of desolate train tracks.

Are you fucking kidding me? I thought.

I’ve had several friends and loved ones struggle with alcohol and drug dependency, only to be helped through years of therapy, medication, and soul-searching. The idea that some app could ameliorate even a fraction of their suffering, I thought, was deeply offensive.

According to the CDC, 91 Americans die every day from an opioid overdose, with excessive alcohol use responsible for an annual average of 88,000 deaths. More than 1 in 6 US adults, or 38 million people, are considered to be binge drinkers. To put it crassly, that’s a big (potential) market for Silicon Valley, and Triggr Health, to tap.

It didn’t help my suspicion that the company used a stock image of “sad troubled woman” to advertise. Even the name, Triggr Health, is a cheeky riff on the “triggers” that can cause an addict to relapse, displaying a critical lack of self-awareness and insensitivity—characteristics that have begun to feel like hallmarks of Silicon Valley disruption. Just look at the recent Bodega kerfuffle or the use of targeted egg-freezing ads on Instagram to women over 30.

There’s a substance abuse epidemic in America, but it’s hard to believe, despite the best of intentions, that tech can actually help us outrun our bio-hardwired demons. But in an era when many have begun to question the validity of traditional recovery methods, perhaps there may be some room for apps to aid in recovery efforts. That is, if Silicon Valley can keep its hubris in check.

Triggr Health isn’t the first app to try to combat addiction—there’s dozens currently available, from Quit That!, which helps users abstain from “coffee and junk food to heroin and meth,” to SoberTool which, like Triggr Health, utilizes rewards and prompts. There are even apps started by former addicts, like WeConnect—a sort of digital AA system that last year raised over $525,000 in seed funding.

And Triggr Health, self-admittedly, isn’t meant for those struggling with serious substance abuse issues—rather, its creator John Haskell told me, it’s for simply helping to acquire a plan-of-attack to combat vices and bad habits. To its credit, if the app senses critical issues, like a mental health crisis or self-destructive behaviors, it will point towards local treatment centers and therapists.

But if it’s so obviously targeting people who need help, Triggr Health still has a clear responsibility to tell users what it can do, and what it can’t, in bold letters.

*

I decided to try Triggr Health firsthand to investigate its claims. At $1.50 for the Basic Plan, $1.94 for Standard, and $4.99 a day for “24/7 unconditional support, daily rewards, and mentors,” Triggr Health boasts the ability to predict regressive behavior with “over 92% accuracy, days before it happens.” It says it uses a form of “mother’s intuition” to predict a user’s needs.Through an on-call text message support system, behavior modifying exercises, and in-app resources, the app promises to give users “tools to establish their own accountability and reach behavioral goals.”

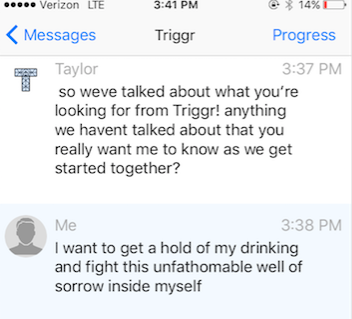

I attempted to be as convincing as possible in the initial diagnostic, temporarily becoming a 33-year-old woman who goes out binge drinking three nights a week, and on remaining nights drinks alone in my apartment (in real life, most nights I’m soberly watching CNN with my boyfriend). I wanted to get control over my drinking, I claimed, but was struggling with an “unfathomable well of sorrow.”

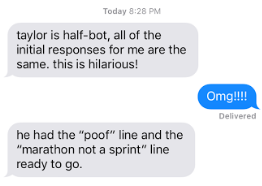

I didn’t want to mention depression outright. Rather, I wanted to see if I left clues and cues, the app would pick up on my underlying mental health issues. I was paired with a guide, a cheery, genderless text message buddy named Taylor. When asked repeatedly if they were a bot, or pressed for personal info, they replied over and over again they were real with a mix of humor and firmness, also telling me there were several “Night Taylors” who handled overnight shifts.

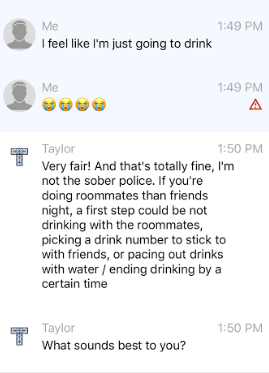

Their responses were so thoughtful that, despite AI-like characteristics and my own cynicism, I was convinced they were real—checking in at the bar, encouraging me to get water between drinks, texting they were proud when I kept goals.

After a few days, I told them I was actually a journalist doing this for a story, mostly because I was tired of lying to a phone. The response was “that’s so cool!!” and a request to see the piece. I asked Taylor how they would’ve handled it if I’d shown serious signs of mental illness or self-harm.

“I wouldn’t say we would handle it so much as just discussing some options. Trying to find the best for them and helping them come to it on their own. Of course, if someone asks us to make a call or do something interventional, then we would.”

I reached out to Haskell, the app’s creator, to learn more about how it was conceived and executed. A 28-year-old Stanford business grad with start-up experience, he explained the inspiration came from watching a friend struggle with addiction and depression only to be helped, on the verge of suicide, by a well-timed text from her mother. (Hence, the “mother’s intuition” sales pitch.)

Haskell said he wanted to replicate this feeling of a mother’s love for mobile download. He explained that “we are non-clinical in nature and focus on behavior change,” helping users reach the goals they’re striving for, whatever those may be. He also confirmed that Triggr Health is not meant to replace therapy, or even formal addiction recovery programs. Rather, it was created to allow users to the tools to help cut down on substances and behaviors and create personalized “paths to long-term remission.”

To gather the research that ultimately built Triggr Health, Haskell partnered with more than 100 addiction recovery programs across the country, working with over 10,000 participants.

The team was able to pinpoint with 92 percent accuracy three days before a participant was going to deviate

“We analyzed thousands of data patterns, such as geolocation, accelerometer, and overall usage, to see if patterns emerged that could indicate whether a patient was going to deviate from their personal recovery plan,” he said.

After noticing trends, the team was able to pinpoint with 92 percent accuracy three days before a participant was going to deviate, using solely data acquired “directly through the application.” He also mentioned continuous research with University of Pennsylvania & University of California in San Francisco’s School of Medicine, among others, ensuring the product was evaluated and built under the care of social workers, therapists, and psychiatrists. The “rewards”? Generally gift certificates or in-app perks.

I asked Haskell if “Taylor” was a real person, thinking back to the therapy-bot ELIZA, built in the 1960s as a sort of proto-Siri for feelings. “We are 100 percent human,” he assured me. “Sometimes, the technology will suggest to the person you work with specific strategies for somebody, and then that person may utilize them or not.” He also let me know that each guide, after an initial orientation, was trained on how to respond effectively to most typical issues. It should also be mentioned that all of the text buddies have the name Taylor, and it’s kept ambiguous whether you’re talking to a man or woman.

I asked why I’d been targeted on Facebook.

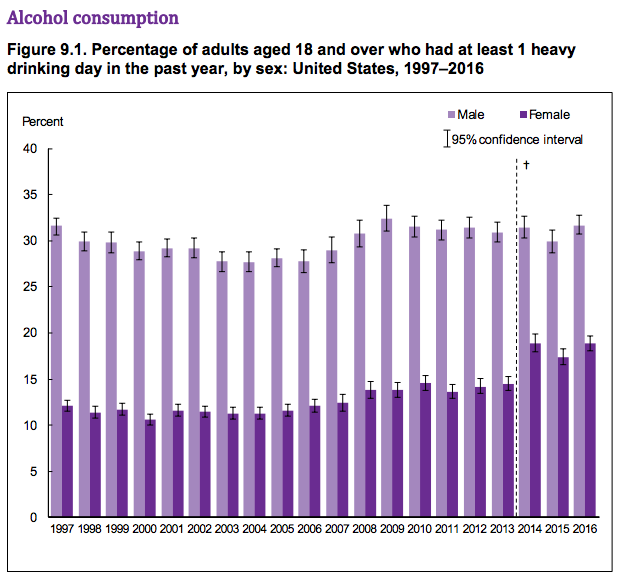

“The majority of people on our platform are female,” he replied, “and tend to be between the ages of 29 and 40.” This may be because women make up the bulk of primarily photo-driven social media like Facebook, where the Triggr Health ad appeared, or perhaps may even be a direct response to the rise of this demographic‘s rampant binge drinking. Either way, it wasn’t a fluke I’d been targeted.

*

I reached out to addiction specialists to suss out whether apps like Triggr Health can be effective in combating these disorders, or achieving the long-term remission that the company promises, especially given that they can often be masking deeper psychological issues.

Dr. Jonathan Howard, a neurologist at NYU’s Langone Medical Center, is widely considered one of the region’s leading brain specialists and often works with recovery programs at Bellevue Hospital, the tri-state area’s premiere center for addiction and mental health treatment. He referenced groundbreaking psychologist, author, and social philosopher B.F. Skinner’s research on behavioral psychology, which concludes that people naturally respond to rewards and avoid harm, but when it comes to drugs and alcohol.

“These are processes that have evolved over millions of years,” he said. “Rats with implanted brain electrodes will work to stimulate certain brain areas even to the point of starvation.”

Howard mentioned the drug disulfiram, which makes people violently ill if combined with alcohol. In many parts of the world, particularly Russia, there’s stock in this method of fear-based alcohol abstinence. This, however, all depends on the patients actually taking the medication. The same could be said for utilizing a technological aid.

“The problem is, people can just stop taking it. The app may suffer the same problem. People can just turn it off. Addiction changes people’s brain in a way non-addictive people can’t understand.”

At the same time, Howard said that utilizing Triggr Health, along with other methods, couldn’t hurt. “We need every tool we have to combat addiction. The worst case scenario is that the app doesn’t work, and that will ultimately be decided by science.”

Sarah Masoodsinaki, an NYC-based psychiatrist specializing in addiction, told me that Triggr Health might address cravings but not the underlying causes for substance abuse, which can often be a mix of nature, environmental factors, and larger societal issues. “Empathy is really lacking in the life of an addict. Pain is real. There is a box of tools for dealing with addiction and they are adding another tool.”

“But never discount the importance of continuing, authentic human interaction,” she added. “Someone who’s there no matter what, not just giving a pep talk.”

*

After a week with Triggr Health, I met up with an old friend. She confided that she was struggling with alcohol abuse and had recently downloaded an app called Vida as a sort of digital sponsor/life coach. She and “Christina” (her text partner) would chat, share recipes, and talk motivational advice. She enjoyed it, even found it helpful, but ultimately the cost ($59 month) led her to pull the plug.

I asked her to download Triggr Health for the free trial week.

After a few days, she texted me to say it felt like “small talk with a Tinder match that isn’t going anywhere,” sending screenshots of a discussion about fresh mozzarella. She thought Taylor was a bot when she compared the responses to mine.

I decided to reach out to another friend, Dan, a musician and UX developer from Manhattan, who for 20 years struggled with alcohol and drug addiction before successfully going sober via the 12 Step Program. “I tried ‘control drinking,’ which only confirmed that I couldn’t manage it. I made promises to myself and my wife at the time—how much I’d drink or when or where or with who, or how much money I’d spend—that were perpetually broken. It wreaked havoc on me and my marriage,” he told me. (To protect his anonymity, Dan’s name has been changed.) “Any system I came up with immediately failed.”

I asked if something like Triggr Health would have been helpful when he was initially going sober. “To simply have an app on my phone wouldn’t have been the level of accountability I needed,” he said. “To speak to other people, make phone calls and meet up in person. Today I use talk therapy and medication in tandem with my 12-step program, and together they’ve been transformative.”

He credits the community of AA, as well as support from a real-life sponsor. “I’m not saying this app couldn’t help. But I have a program that’s allowed me not to drink in over eight years,” he said. “While it might be easy to lie to an app, in AA I had to be honest with others and myself about my cravings and feelings that could lead to drinking.”

“To simply have an app on my phone wouldn’t have been the level of accountability I needed”

Psychiatrist Marc Galanter, Director Division of Alcoholism and Drug Abuse at NYU’s Langone Health center and author of What is Alcoholics Anonymous? A Path from Addiction to Recovery, told me that decades of research have shown that battling addictive impulses comes less from breaking embedded habits or conditioned behaviors than a total transformation—even establishing a whole new attitude towards yourself as a person.

“The social support of people who are working to become abstinent is initially what’s most effective. Over time, it helps them basically get ahead of that conditioned reflex.”

So where does Silicon Valley’s idea that we can outsmart millennia of brain evolution with the click of a button actually come from?

“Developers are engineers. They’re coming from the perspective that most of humanity’s problems are not pre-existing conditions of nature, but problems of design,” said Doug Rushkoff, a writer, documentarian, and NYC-based lecturer whose work focuses on human autonomy in a digital age. “Where we get into potential trouble is when we apply the engineering mindset to nature. We just don’t know that much about these very complex [brain] systems.”

Simply “hacking addiction,” or any other human behavior, is easy—as easy as using slot machine mathematics to induce compulsive behavior in smartphone users—but influencing long-term behavioral change requires engaging deeper work. Often, a text just isn’t enough to dispel our worst impulses.

After a week I checked in with my friend on Triggr Health.

“There are things I like about it and things I don’t,” she texted. “But it’s actually really helpful for nights when I’m home and don’t want to drink alone. To have someone to talk to about whatever I’m cooking, reading, watching for a distraction. It encouraged me to take a walk last night and listen to a podcast, to get out of the house. To be fair, that was helpful.”

Apps like Triggr Health may never fully replace real, genuine human contact, but if they’re able to help those struggling with issues, to be “another tool in the toolbox,” then who are we to discount their usefulness? As substance abuse in America increases exponentially, and our lawmakers performatively wring their hands, we really can “use all the help” we can get.

Even if it’s just a text, asking “hey, want to go for a walk?”

Get six of our favorite Motherboard stories every day by signing up for our newsletter .