How to Spot a Fake $1,000 Magic: The Gathering Card

Credit to Author: Matthew Gault| Date: Mon, 30 Oct 2017 17:12:48 +0000

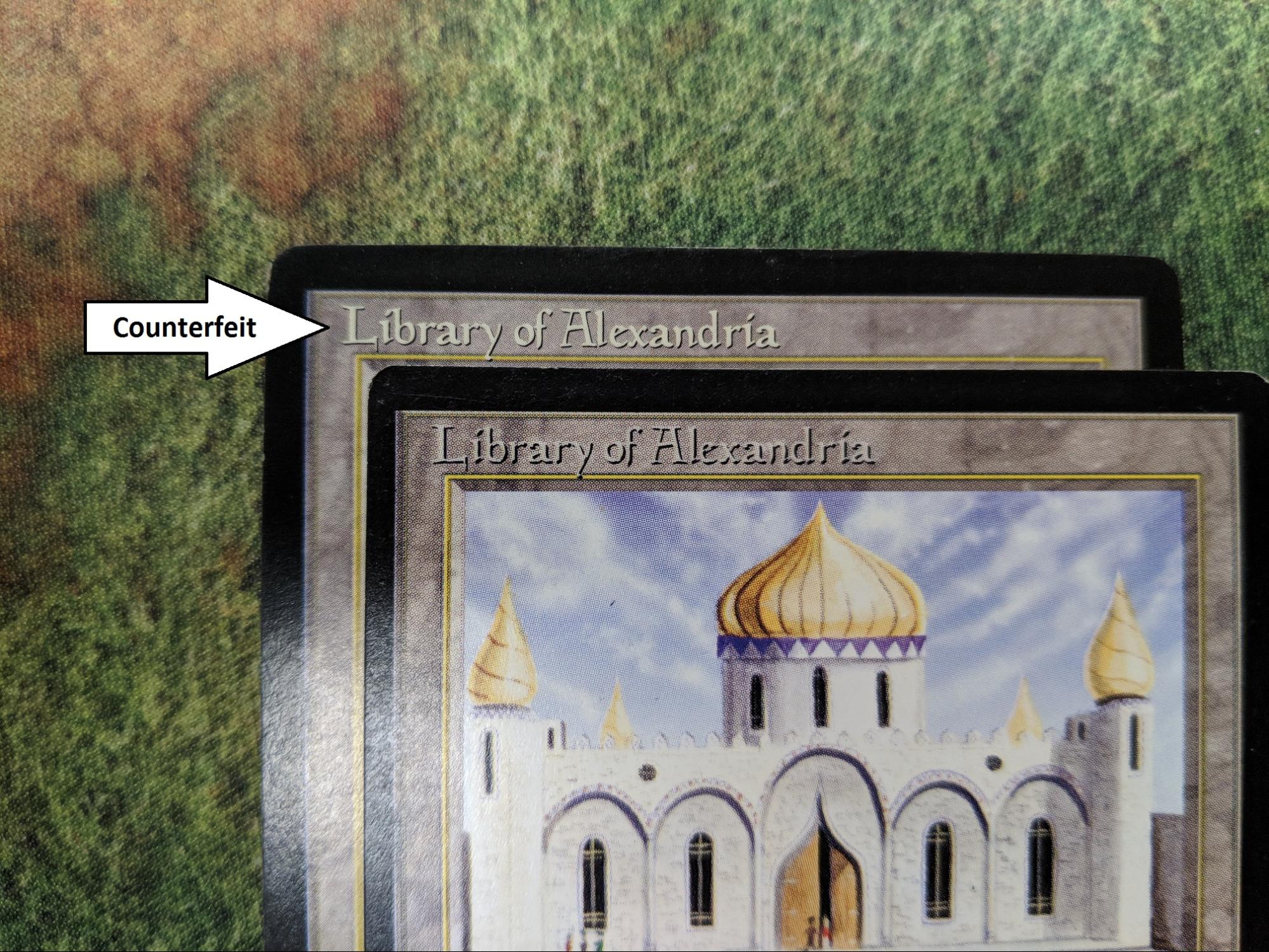

The moment I touched the card I knew it was fake. It was a great looking counterfeit, but a counterfeit all the same.

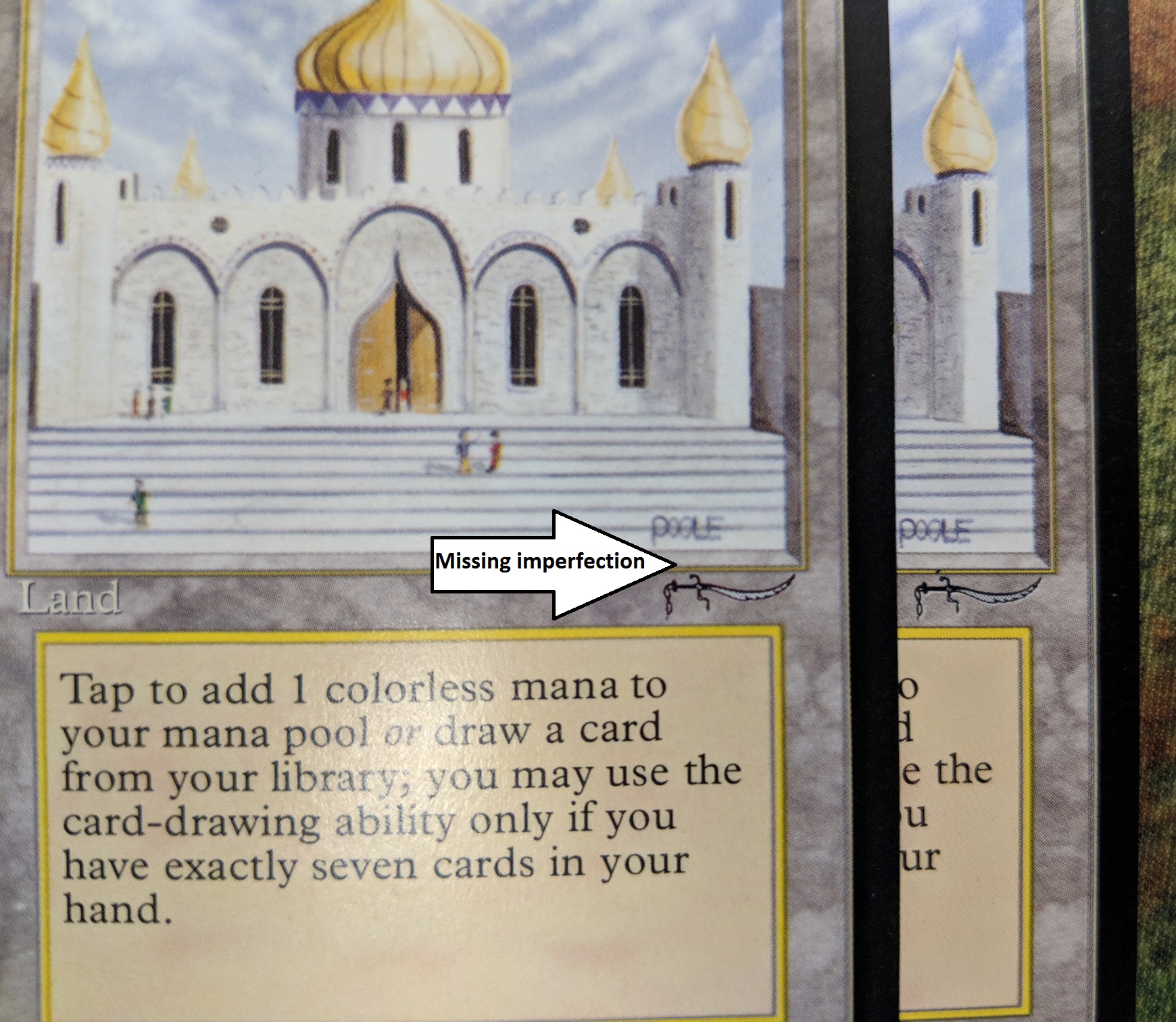

“That’s a card called Library of Alexandria, printed in 1994,” Teddy Carfolite—a South Carolina school teacher and avid Magic: The Gathering player told me. “There’s under four or five thousand of those left on the market. Players who play the oldest format all want to own one. Everyone who plays wants to own one and you know [Wizards of the Coast] is never going to reprint it…it’s an investment opportunity.”

The slight piece of cardboard I held in my hands would be worth somewhere between $500 and $750 if it were real. But it’s not. It’s a competent forgery printed on demand in China. It’s worth only whatever the buyer paid for it, probably less than a dollar.

I was sitting in Ready to Play Trading Cards in Columbia, South Carolina, and Carfolite has laid out dozens of pieces of glossed cardboard in front of me. He’s not an employee of the store, just an avid collector, and he wanted me to know that neither he nor his favorite card shop endorsed or sold the fakes. But they did keep them around as a teaching tool.

The cards are from Magic: The Gathering, a popular trading card game created in 1993. In the two decades since Magic’s original release, the game has grown from a hobby shop standard to a multi-million dollar industry.

Players buy packs of cards, build them into decks, and fight their decks against opponents. New Magic cards typically come in packs of 15 sealed in a booster pack. Thirty-six booster packs makes up a booster box. Each pack contains a random assortment of cards distributed by rarity. Some cards are more powerful, and therefore more expensive on the secondary market, than others.Millions of players all over the world play Magic: The Gathering. Every Friday night, hundreds of thousands of players descend on their local card shops to participate in licensed tournaments. Millions more players, such as myself, stay out of the official system and play casual games with their friends.

It’s in these casual settings where the dark parts of Magic: The Gathering take root. The prize pools for the tournaments can be hundreds of thousands of dollars, but the consistent money is in the cards. Especially the older ones. Cards like Lotus can sell for upwards of $10,000 or more on secondary market sites such as Ebay.

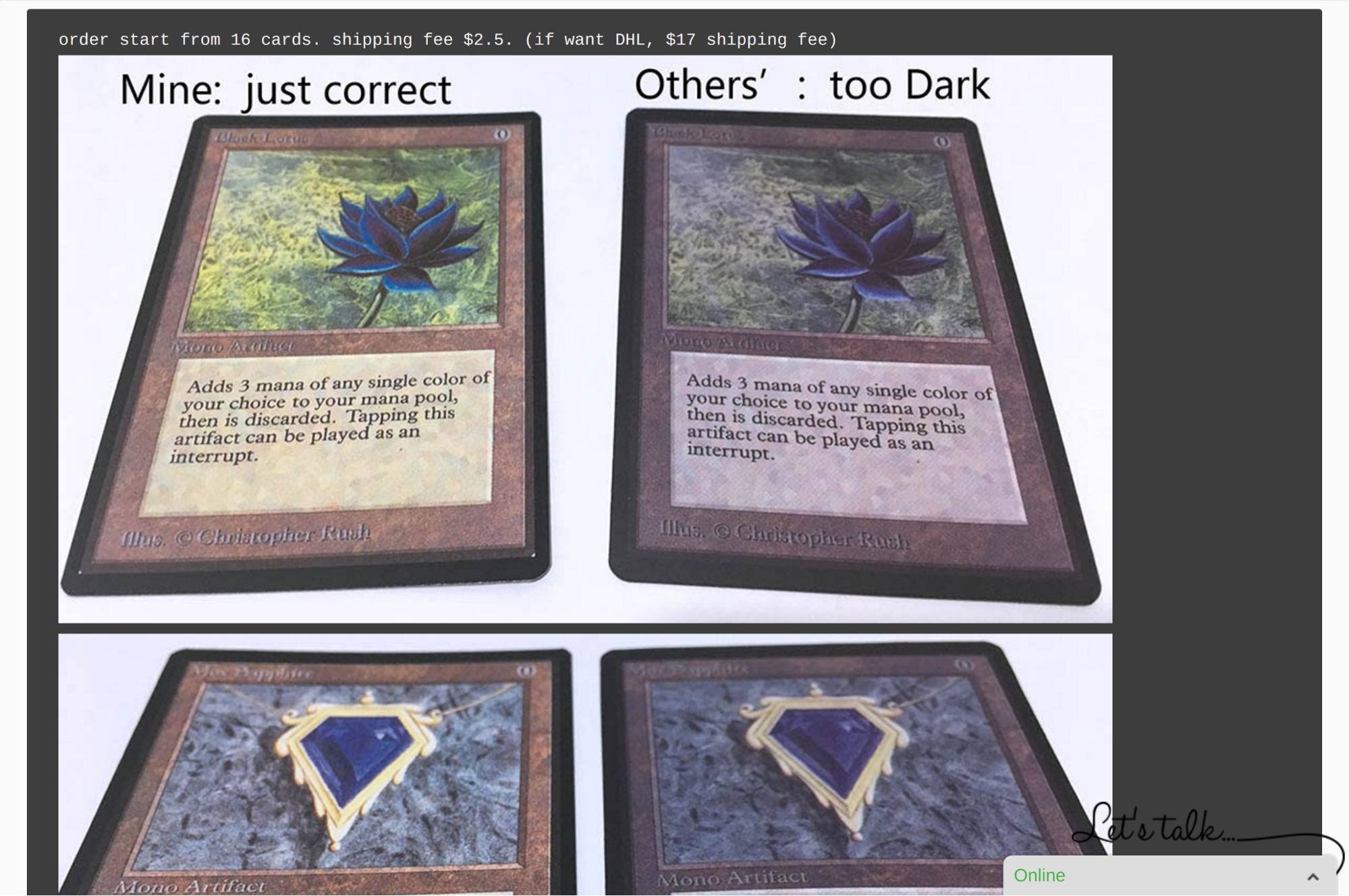

With that much money on the table, unscrupulous printers have flooded the market with fakes, proxies, and counterfeits. It’s an old problem. Fakes have been around since I started playing back in the late 1990s, but they’ve changed. The quality has improved and it’s getting harder to tell the fakes from the originals.

Counterfeiting was once a boutique trade. Lone counterfeiters used to run an operation in their homes, printing out stickers on a home printer to lay over cheap Magic cards in an attempt to pass them off as the real thing. Two of the sources I spoke with, Carfolite and Robin Hood Dial—another South Carolina Magic collector—said it used to be done with an Epson printer and some glue. The counterfeiter printed up the card they wanted and glued it to low value cards so the back looks right. A few years ago, everything changed.

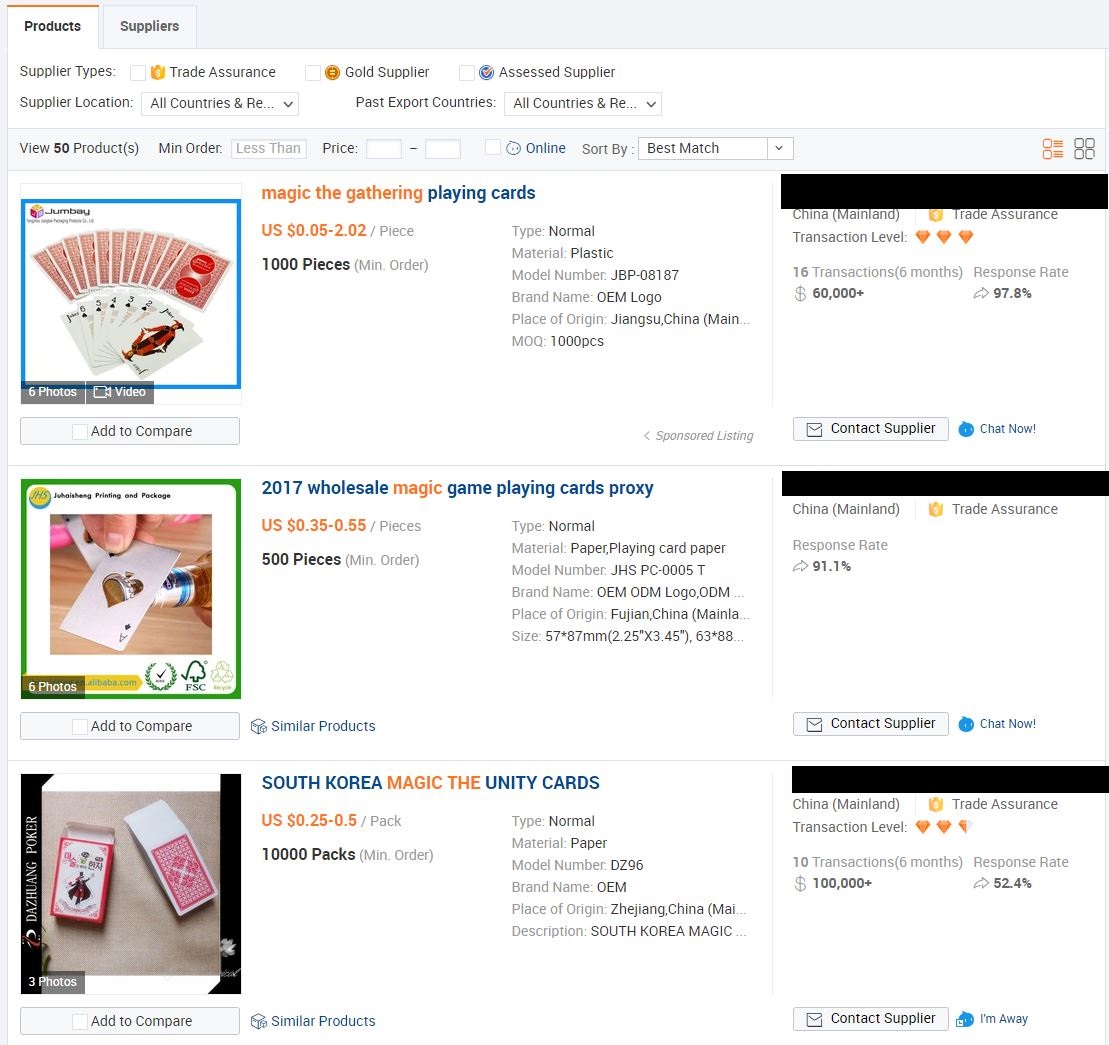

Overseas printing companies—most of them operating in mainland China—now print sets in bulk and sell them through sites like Alibaba. Getting a whole set of old, out-of-print cards is as easy as Googling “Magic proxies,” contacting a vendor, and using PayPal to order a full set of the Power Nine—the rarest, most expensive, and powerful cards in the game.

At first glance, the Library of Alexandria Carfolite showed me is close to perfect. Except for the feel. After years of playing Magic, your hands get used to the weight and texture of the cards. Counterfeits all feel off. Some are too smooth, others too rough, and the weight is often wrong. Carfolite told me that was the number one way he can identify a counterfeit. The closer you look the more the differences jump out.

“The gloss plays a big part,” he said. “Which is scary because now people are taking magic erasers to them and dulling the gloss. Fonts are never perfect. In the titles…see how the font’s are different. It looks raised on the real card.”

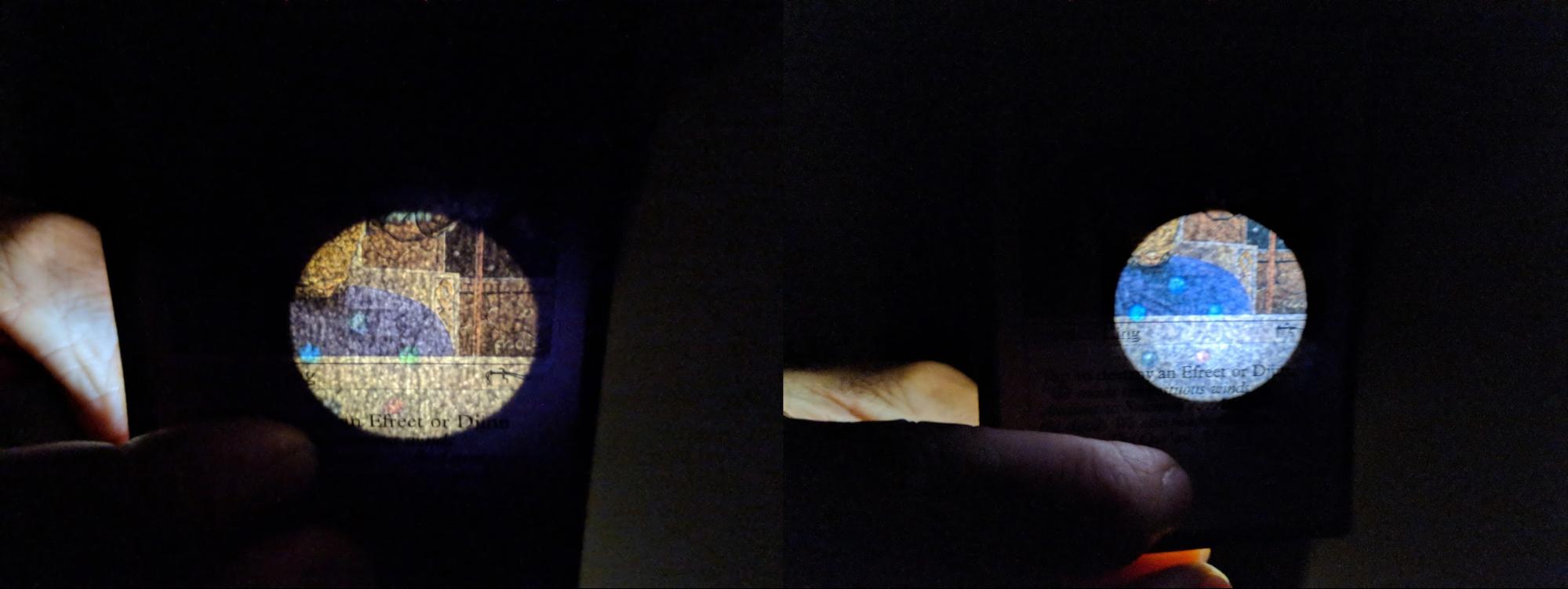

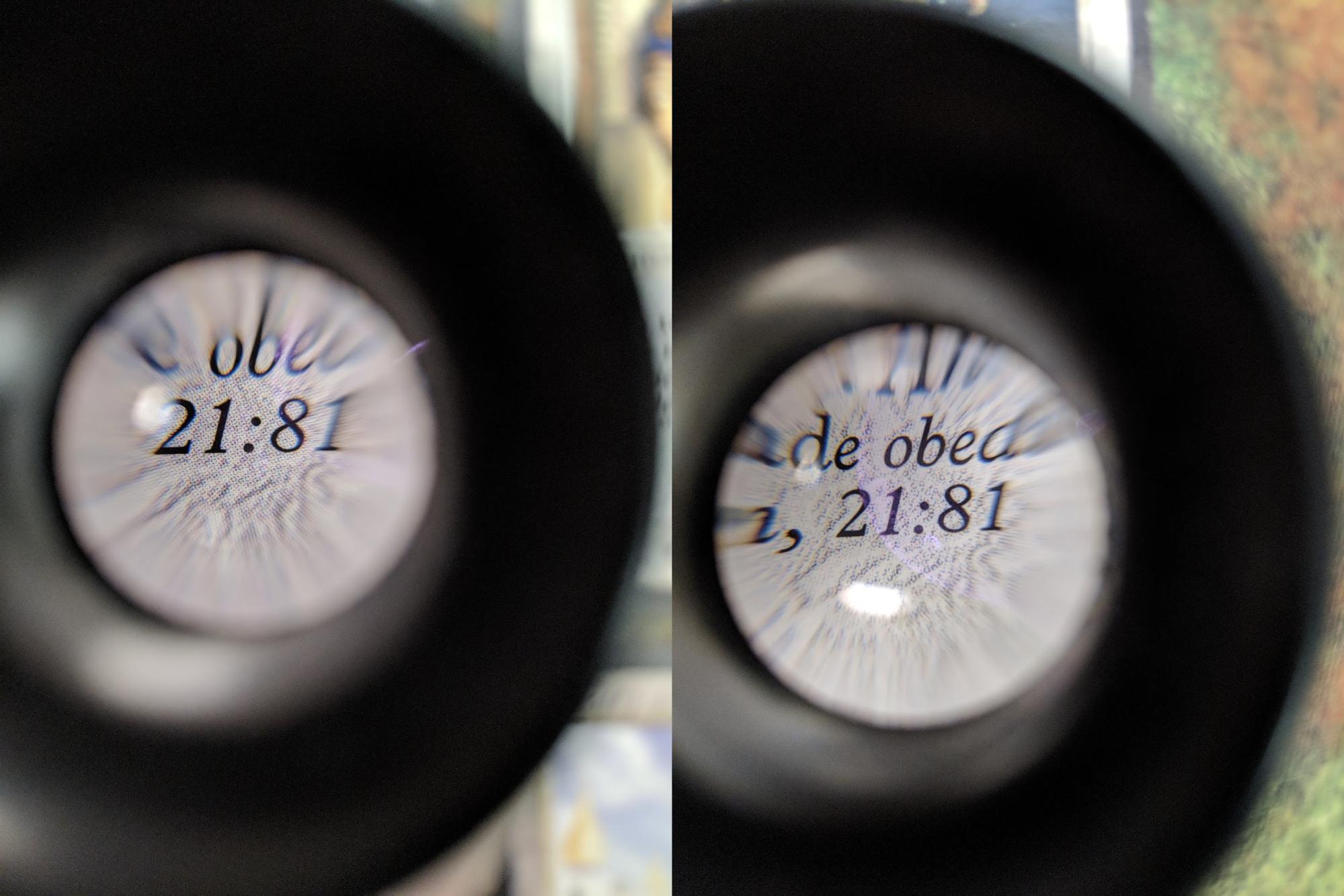

There’s many different ways to root out a fake Magic card, but everyone has their favorite and some methods are more popular than others. One of the oldest is the light test—the practice of using an LED flashlight to shine through a card.

“On the old stuff, the most distinguishable sign is the light test,” Rudy, who dispenses financial advice on buying Magic cards on his YouTube Channel Alpha Investments LLC, told me over the phone. He withheld his last name because he said he’s been hacked and doxed in the past. “You shine an LED light or your phone flash light on your card. If it has a white tint or certain other signs, you know whether it’s fake or not.” Rudy is a popular YouTuber whose videos shine a light on the seedier side of Magic: The Gathering. He talks counterfeits, repacks, and the lucrative commodity market.

Depending on who you ask and which YouTube videos you watch, the light test is either a fool proof method of detecting counterfeits or a complete waste of time. The basic idea is that a flashlight on full blast will cut through a legit card and show through on the other side, while a counterfeit card will either block the light completely or dull it significantly.

“I don’t take a lot of stock in the light test,” Tony, a Texas comic and gaming store employee who wished to remain anonymous to protect the store’s reputation, told me. He said that people spread disinformation about what happens when the light hits a card. Some say newer cards have watermarks and that different sets had different internal patterns. Most of that is simply wrong.

Carfolite also urged caution when using the light test to determine the authenticity of cards. “I’ve heard of unsavory vendors [using] lights with two different settings,” he said. It’s an easy way to beat the test. Take a real card and shine the light through at low setting to get a base read, then turn the setting up to high and blow through a counterfeit card and get a similar showing.

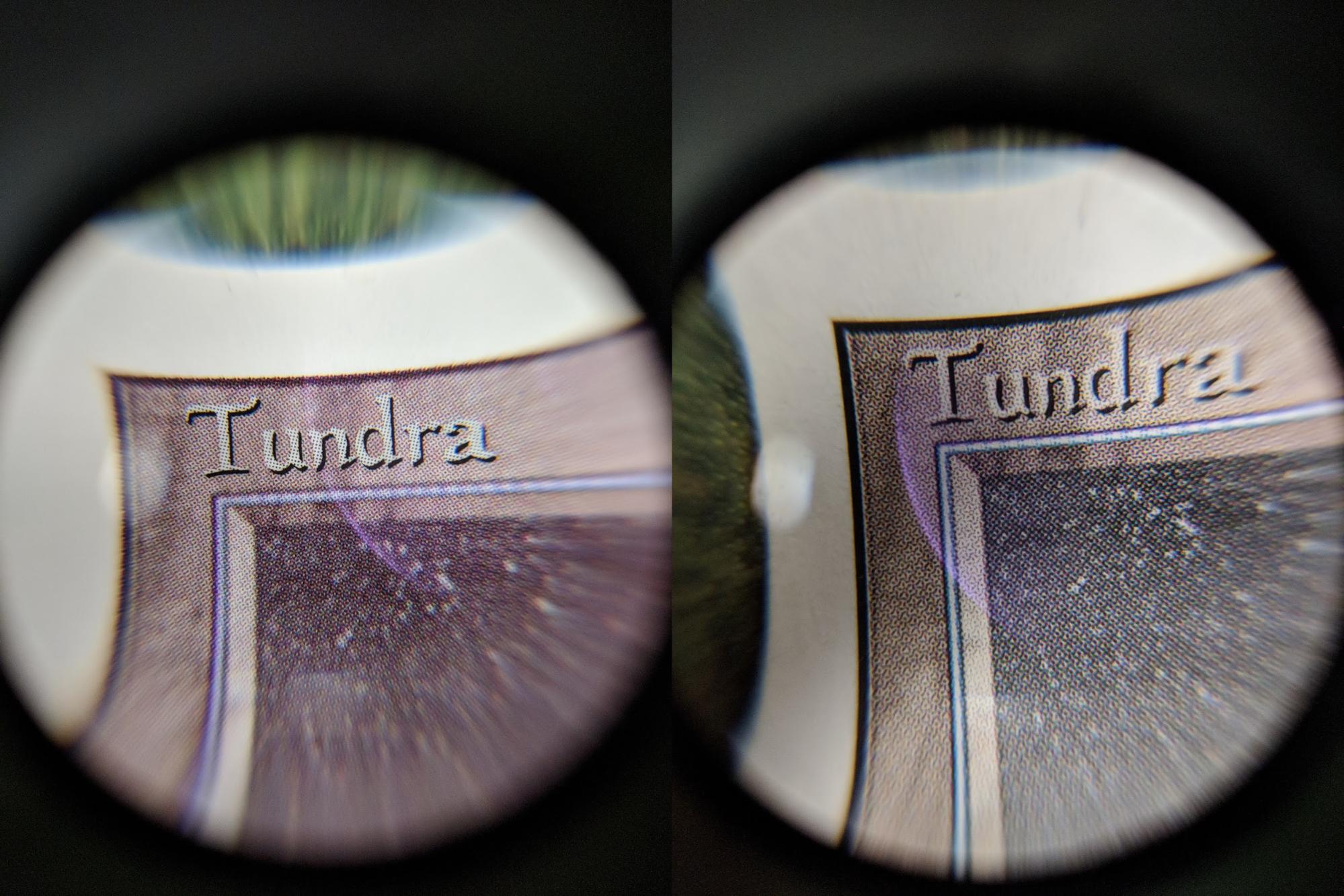

Tony’s store is huge and it buys a lot of Magic cards from its community, so it’s important that he and his staff understand how to spot a fake. He’s got a team of seven and they all carry jeweler’s loupes, magnifying glasses they use to study the pixelation of the cards.

There’s other identifying features beyond the pixels. “On the older cards we go by margins around the borders,” Rudy told me. “The older cards had different margins and they’re very distinguishable compared to newer cards. The way they flex and the way the bend. The depth of colors. How bright or faded they are. At ten-plus magnification you can look at the dot patterns on the front and back of the card to look at the rosettes or the rosetta dot pattern and actually match it with an authentic card.”

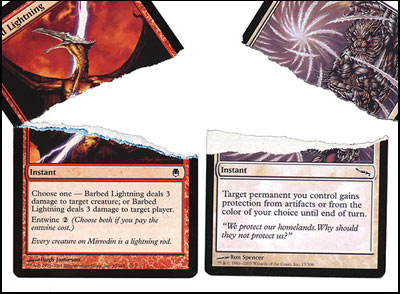

Everyone I talked to spoke of the dreaded nuclear option for detecting a fake—ripping it apart to look inside. “All Magic cards have a blue core in between,” Rudy told me. “There’s a blue core sheet that goes in the middle. It’s difficult to duplicate. If you do try to do it all, it’s not going to bend correctly, the light’s not going to go through it correctly. The feel of the card is going to be very different to replicate unless you’ve got these [expensive] machines from the actual corporation [printing Magic cards].”

“We hate to do that…but a lot of time it’s worth it,” Tony told me. At his store, high-rolling collectors will sometimes come in with sets of Magic cards that retail for tens of thousands of dollars.

“If you can eyeball a collection and assess it’s worth $4,500 … well… maybe I pay $4,600 in the end but you buy one of their Volcanic Islands at full retail price. No questions asked,” he explained, referring to a popular card printed in 1994. “You’d be foolish to turn down $200 for something I’m going to sell for $200. So we’ll pay them and then rip the card…sometimes, that’s just necessary.”

Tony’s solution to the problem of counterfeit cards is a good one. It’s also not feasible for most stores. Smaller card shops that cater to the Magic community can’t afford to pay for something it intends to destroy just to test the authenticity of an individual buyer. They just don’t do the volume.

Carfolite’s collection of counterfeit cards also came from people who came into the card shops to sell them. He didn’t get into the specifics of the deal the card shop he frequents made to acquire them, but he did tell me that Ready To Play Games does attempt to buy fakes to take them off the market.

Tony’s store does the same. “We can’t have that stuff floating around,” he said. “We acquire stuff and destroy it.”

But not everyone walking around with counterfeit Magic cards is a scammer looking to get one over on a local card shop. A lot of the people buying fake cards from online vendors are just fans who want to play with the old cards without spending thousands of dollars.

“Very early on in [Magic’s] history, [Wizard’s of the Coast] over printed some cards and it upset the secondary market,” Carfolite said. “So they made what’s called the reserved list and they promised to never reprint cards. What’s happened is that lost of people think that counterfeiting is OK when it comes to reserved list cards.”

In the mid 1990s, Wizards of the Coast published the fourth edition of Magic: The Gathering. A year later, it published Chronicles—an expansion to the game that reprinted some of the hard-to-find cards from previous sets. Some fans were thrilled but collectors with expensive cards from the early sets watched the price of their collections plummet on the secondary market.

To appease the game’s longtime fans, Wizards created the reserved list—an expanding list of cards it’s promised to never print again. The rarest and most expensive cards in Magic are the ones that sit on the reserved list, but just because those cards are now a commodity doesn’t mean players don’t want to play with them.

Wizards runs officially licensed tournaments, but there are thousands of other unofficial tournaments where anything goes. At those unofficial tournaments, organizers tend to allow people to play with what they politely call proxies—counterfeit cards that stand in for the originals in a played deck.

“It’s en vogue right now,” Robin Hood Dial, the other Magic collector I spoke with, told me. “You can only use cards from the original sets and maybe a little bit of Legends and Arabian nights. But no one could be expected to be playing with the Power Nine originals.”

Some people buy from Chinese vendors to fill out a proxy deck to play in a local tournament. Others spend pennies on the dollar to mass produce fakes to flood the secondary market. “It’s a mixed bag,” Dial told me.

As the counterfeit cards filter into the secondary market, hardcore collectors have started to trust open product less and sealed product more. “You’re going to see a reduction in older cards and a resurgence in trading new cards,” Tony told me. “Stuff that came out of the box today. Things that are more trustable.”

There are dozens of other ways to buy Magic in various packages, but booster packs and boxes are the most common. Counterfeiter’s have started to produce sealed booster boxes. One of Rudy’s YouTube videos details the process by which scammers can bust open a sealed booster box, fill it with fake product, then reseal it to sell back to unwitting victims.

“You might buy a booster box of something from China and every card in every sealed pack is full of the same card,” Dial told me. “Worse, it won’t even be a valuable card.”

It’s bizarre, but rare. “It sounds like a simple thing to copy but it’s actually difficult to do,” Rudy said. “Of the thousands of booster boxes I’ve seen, I’ve seen maybe one or two resealed. I don’t think it’s a big market … individual packs are a lot easier.”

Resealing those individual boosters is called repacking or resealing and it’s as old as Magic itself. When I was a kid, my local gamestore had a display at the front of the counter. There was a pile of resealed magic packs, each containing ten randomized cards, with a sign promising that some lucky kid would get a Black Lotus—the rarest and most expensive card in the game— from one of the packs. The rest of the cards were probably garbage, but it was a thrill to buy some random repacks on the off chance of scoring a Black Lotus.

Brick and mortar stores have turned away from the practice of pushing repacks and the business has moved online. “Technically, there are two types of repack,” Rudy told me. “The first type…is when someone—an individual or a store—opens [a booster] and reseals it in an attempt to sell it as an original, factory sealed pack, which is the biggest no-no. Wizards can ban you if they catch you.”

The second type is the more traditional, up-front repack that’s spreading on online stores like Amazon and Ebay right now. What makes them so insidious is sellers often make big promises about the rarity of the cards they’re selling in the repacks but don’t always follow through.

Worse, some of the resellers are offering cash to popular YouTuber’s to shoot videos opening repacks in videos. There are hundreds of videos of people opening up repacks on YouTube and being shocked and overjoyed by the contents. Rudy told me one repacker offered him $1,000 to shoot a pro-repacking video. Instead, he exposed the scheme on his channel.

To hear him tell it, the world of Magic: The Gathering is experiencing an uptick in repack selling right now and it’s driven by YouTube. “It’s a loophole for gambling,” he said. “As of now, Ebay allows repacks. They don’t pull them. They look the other way. They allow them to be placed on their marketplace because they don’t see it as gambling in their eyes. I disagree.”

I reached out to Wizards of the Coast about the secondary market and what it’s doing about repacks, counterfeit cards, and proxies. “We can’t comment on specific tactics or investigations, but we can say that we take intellectual property theft, including counterfeiting, very seriously,” Wizards said. “Our investigation team is second-to-none in the gaming industry and works closely with state, federal, and international law enforcement partners to target and stop counterfeiters.”

The printing shops on Alibaba come and go. During the course of reporting on this story, I monitored several vendors on the site. They always advertise MTG reprints in the description, but only show Bicycle playing cards in the pictures. When one shuts down a new one takes its place.

Rudy and Tony told me that Ebay and Amazon routinely chase proxy vendors off their platforms, but more come to replace them every day. As of this writing, there were several reprints for sale on Ebay. The dark side of Magic isn’t going away. “The amount of money in Magic is absurd,” Rudy told me. “If you know where to get it.”

Everyone I spoke with admitted that the fakes were getting closer and closer to being indistinguishable from the real thing. “What’s scary is that four or five years ago, [counterfeit] cards looked much worse,” Carfolite said. “People put a lot of effort into getting them and beating them up a little to make them look real. The counterfeiters have benefited from the fact that they’re so rare and valuable that they sleeve them and it makes it hard to tell.”

Tony’s hopeful and though he thinks the counterfeits will continue to disrupt the game, they’ll never stop it. “There are too many people who want the product for being able to shuffle it and play it in the game,” he said. “That’s what this is. It’s a really expensive game. As long as there’s people who want to buy a card and play it in a game, the game will always be there. Counterfeiting cards won’t kill that.”