Hong Kong Has No Space Left for the Dead

Credit to Author: Justin Heifetz| Date: Mon, 23 Oct 2017 13:00:00 +0000

This story is part of OUTER LIMITS, a Motherboard series about people, technology, and going outside. Let us be your guide.

When Fung Wai-tsun’s family carried their grandfather’s ashes across the Hong Kong border to Mainland China in 2013, they worried Customs officers, thinking the urn was full of drugs, would stop them.

Fung, like many others in Hong Kong, could not find a space to lay his loved one to rest in his own city and would have to settle for a site across the border and hours away.

It’s an increasingly common story as demand for spaces to house the dead outpaces supply here in the semi-autonomous Chinese territory of some 7.4 million people. Hong Kong’s public, government-run spaces to store ashes—which are affordable to the public, starting at $360—have waiting lists that can last years.

But many Chinese, like Fung, strongly believe the ashes must be put in a resting place immediately as to not disrespect their ancestor’s spirit.

Read more: Hong Kong Has Nearly Run Out of Space to Put Its Garbage

Meanwhile, a private space—one that is not run by the government—tends to start at more than $6,000 and can go for as high as $130,000. This is simply not an option for many families like the Fung’s.

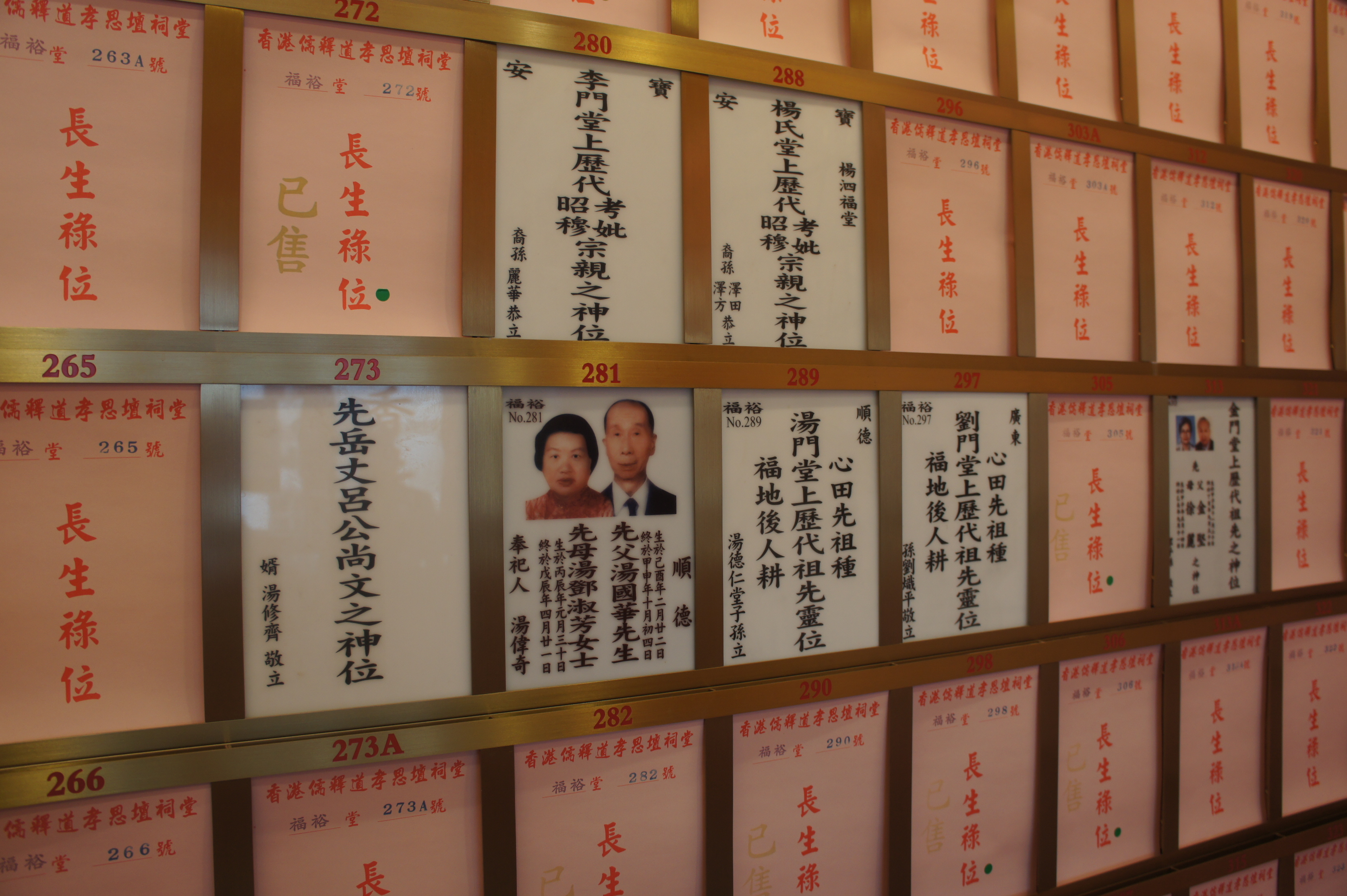

In Hong Kong, most people cremate their loved ones and house the urns in columbariums, or spaces where people can then go to pay their respects. While burying a body is possible, the option is prohibitively expensive—and besides, Hong Kong has a law that the body must be exhumed after six years, at which point one must be cremated.

So the Fung’s went to the bustling southern city of Guangzhou, where spaces for ashes are far more accessible, to purchase a place for his grandfather’s urn. “We would have chosen Hong Kong if spaces were available, or cheaper,” Fung told me.

“We have people living in sub-divided housing, so if you talk a lot about dead people, no one gives a shit.”

Fung is a grassroots Hong Konger, a 28-year-old debate teacher whose family emigrated from Mainland China years ago. Today, his family visits the temple where his maternal grandfather’s ashes are stored usually once a year on Qing Ming, the Chinese tomb-sweeping holiday. The commute from Hong Kong is about three hours one way.

“In Hong Kong, there’s very little choice of where we can put the dead,” said Fung, who pointed to the abject poverty and housing shortage facing the city’s working class as reasons why making space for the deceased is being overlooked. “We have people living in sub-divided housing, so if you talk a lot about dead people, no one gives a shit.”

In fact, finding adequate space for the dead is about to become even more difficult in Hong Kong. In June, a sweeping law went into effect demanding that private funeral businesses apply for a new license. The government projects that about 80 percent of those businesses will fail to meet the new standards and be shut down by March 2018. This will put almost 400,000 spaces occupied with urns at risk of displacement, according to Alnwick Chan, executive director of property agency Knight Frank.

“The government should be more pragmatic to allow this sort of business in a regulated environment,” Alnwick Chan told me. “We’ve got to find a way to house our ancestors’ ashes.”

But aside from the new law, private funeral businesses already face a considerable hurdle: nobody wants them.

Many Chinese believe in ghosts—a haunting spirit in every urn that’s not their own ancestor’s—and also that those ghosts massively bring down property prices. In the world’s priciest housing market, it is hardly surprising that property owners are staunchly against new funeral businesses in order to preserve their sky-high rents.

Those in Hong Kong who want to try their hand at winning a coveted public columbarium space can expect a wait.

According to the Food and Environmental Hygiene Department (FEHD), the government office overseeing cemeteries and crematoria, public spaces are obtained through a random lottery—and there won’t be another lottery until the end of 2018. Hong Kong has about 50,000 deaths each year and there are now no vacancies for new urns anywhere public in the city.

For many, finding space for the dead across the border may be the only option left—and some entrepreneurs are taking note.

*

A monk lets off a long, deep hum for the dead.

On the second floor of a no-frills walkup in Hong Kong’s gritty Sham Shui Po neighborhood, where decaying neon signs hang over a crowded electronics market—a mess of off-the-truck wires stitched up to poles under humid tarpaulins—seasoned businessman Alex Chan has converted an average space into an urban temple. When I first enter, the monk leads a family through the hallway in prayer. They stand facing a stone tablet—behind it, a space for the urn—bearing an inscription of the deceased relative’s name.

But the dead’s ashes aren’t actually there behind the tablet; the ashes aren’t even in the building. The urn was carted off to Guangzhou long ago, where spaces for dead people come without the years-long waiting list or astronomical price tag.

“We think we have a good future,” Alex Chan told me. “Since May, we have dealt with more than 100 deaths.” And by April, once Hong Kong’s new funeral licensing law is in effect and the government begins to shutter private businesses that don’t meet the revised standards, he asks me, “Where will the bodies go?”

The tablets are largely symbolic. His business is not registered as a private columbarium, so he does not store people’s ashes. Instead, he runs what is essentially a cross-border funeral agency—finding Hong Kong people spaces for the afterlife in Guangzhou. The urban temple is simply for his clients’ peace of mind, a place to worship and pay their respects to ancestors without having to trek to Guangzhou.

Yet he said it’s often not painful for his clients to have to leave their homes and bury loved ones across the border, sometimes in an unfamiliar place. “The environment is better [in Mainland China], there’s a better space, and better service than in Hong Kong,” Alex Chan said. “The Hong Kong government does not provide this.”

But sometimes there are unforeseeable problems when it comes to being buried across the border. Fung’s paternal grandfather recently passed away and his grandmother is too ill to travel to Guangzhou, so the family decided that he must be buried in Hong Kong for her sake. His ashes have been on the waiting list for a public columbarium for one year. The urn will finally be transferred from the funeral planner’s office—where the ashes, without a proper home, have been a source of anxiety for the Fungs—next month.

Fung said that where his maternal grandfather’s ashes are kept in Guangzhou is undoubtedly more beautiful and spacious than the public columbarium space where his paternal grandfather will be put in Hong Kong. The space on the mainland, where monks clean and pray daily, cost Fung’s family about $2,500; in Hong Kong, Alex Chan said a similar space at a private columbarium could cost around $60,000.

But Fung still worries over what could be disastrous. The Hong Kong government showered his family with official paperwork for his paternal grandfather’s public space. The Guangzhou temple, by contrast, gave them no forms or contracts save a receipt of purchase. If it’s fair to say many large and small businesses in Mainland China run on guanxi —best translated as “relationships”—then temples like the one in Guangzhou, which are often unlicensed, would likely shut down should guanxi sour with the government.

“There’s no assurance the temple can store the ashes permanently,” Fung explained. “The worse case would be that the government destroys the urns.”

*

The Diamond Hill Crematorium is a large public columbarium with a seemingly endless maze of spaces for ashes and tombstones. On a recent Tuesday afternoon, families light incense and leave small trinkets in front of their ancestors’ tablets. A few old men stroll through the stone memorials strewn across a green hill, trailed by stray dogs.

One thing does feel out of place: The columbarium is plastered with large signs urging people to do the right thing by scattering their relatives’ ashes, be it over the ocean or in public gardens.

This is the government’s answer to accommodating the city’s dead, rather than making more space for them. Scattering ashes goes harshly against the culturally Chinese concept of respecting the ancestor’s spirit with a permanent home.

The government calls scattering ashes “green burials” despite the fact the body is still burned and emits carbon. In a written statement to Motherboard, a spokesperson for the FEHD said the government is pushing to make this the preferred choice for burials across the territory.

As for whether crossing to Mainland China for burial spaces is encouraged or discouraged, the government has no particular stance. “It is entirely the free choice of people to determine the ways to handle the remains of their loved ones,” the FEHD spokesperson wrote.

Alnwick Chan, the property agent, suggests government explore the option of building a large-scale columbarium on one of Hong Kong’s many outlying islands. But he admits that this would be unlikely given the government’s exhaustive to-do list tackling its housing problems. So for now, he thinks finding a space for ashes across the border just may be the best option.

“Turning to Guangzhou is one of the good ways to solve Hong Kong’s problems,” he told me. “It would relieve the pressure of demand, if the land is legally meant for that purpose.”

Fung, for his part, sees the lack of space to house the dead as an administrative failure, which isn’t unusual in today’s Hong Kong, an increasingly politicized city where younger generations, especially, are growing disenfranchised. He said that if the government acted on finding more land, it could immediately solve the crisis in accommodating its dead.

Fung’s predicament feeds a paradox that complicates death in the Chinese metropolis. He feels the city must build more funeral businesses so that there can be accessible and affordable spaces for relatives like his grandfather. But at the same time, he would be resistant to that new columbarium going up in his own neighborhood.

“It’s an inevitable conflict,” Fung said. “We respect our ancestors, but we don’t want to live with the spirits in their urns.”

Get six of our favorite Motherboard stories every day by signing up for our newsletter.