A New Collection of Nature Illustrations Is a Window Into 19th Century Science

Credit to Author: Becky Ferreira| Date: Fri, 20 Oct 2017 13:00:00 +0000

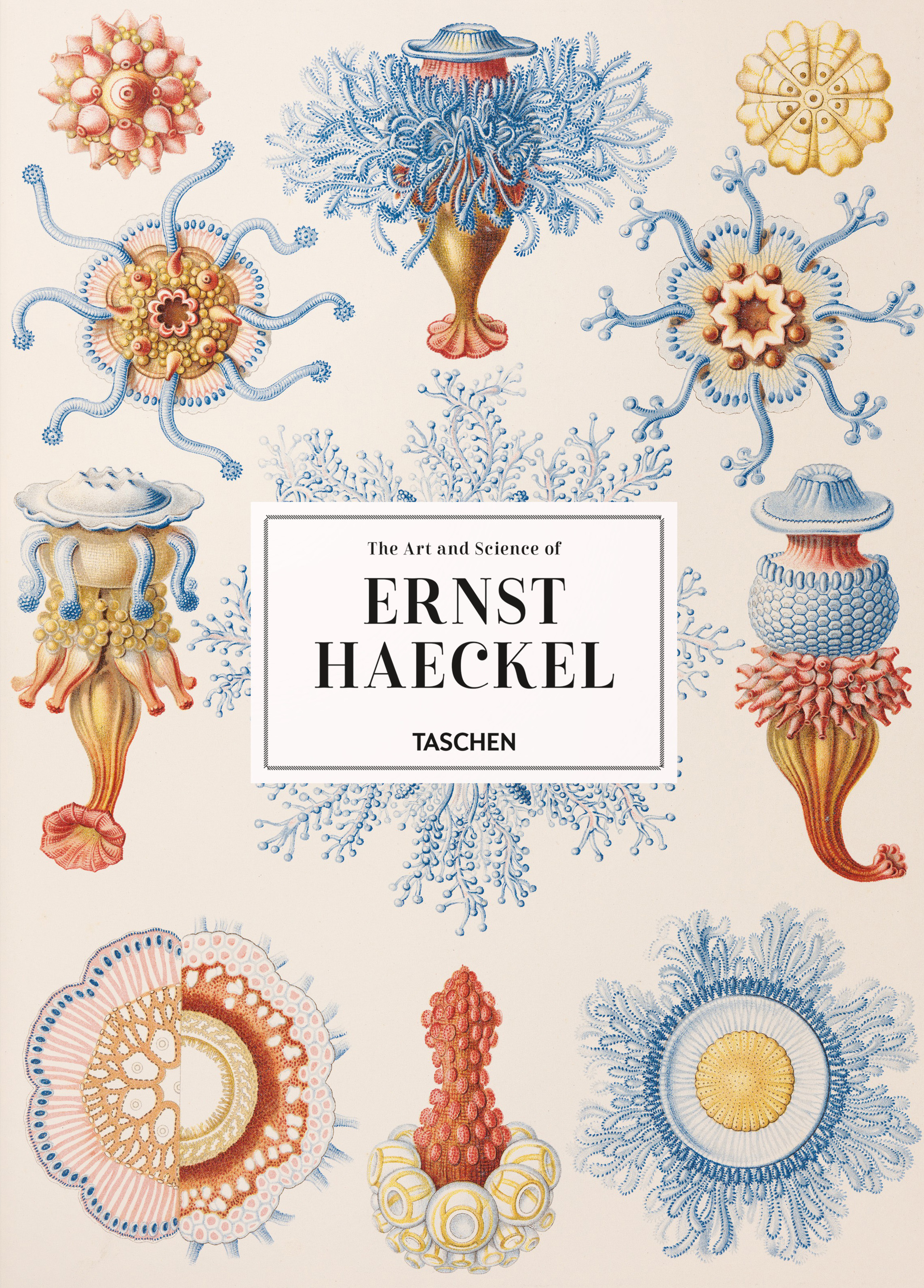

It’s no small feat to become “both one of the best-loved and one of the most hated men” of an age. But Ernst Haeckel, a German naturalist and scientific illustrator who lived from 1834 to 1919, earned this mantle from his contemporaries, according to The Art and Science of Ernst Haeckel, a new art collection just out from TASCHEN.

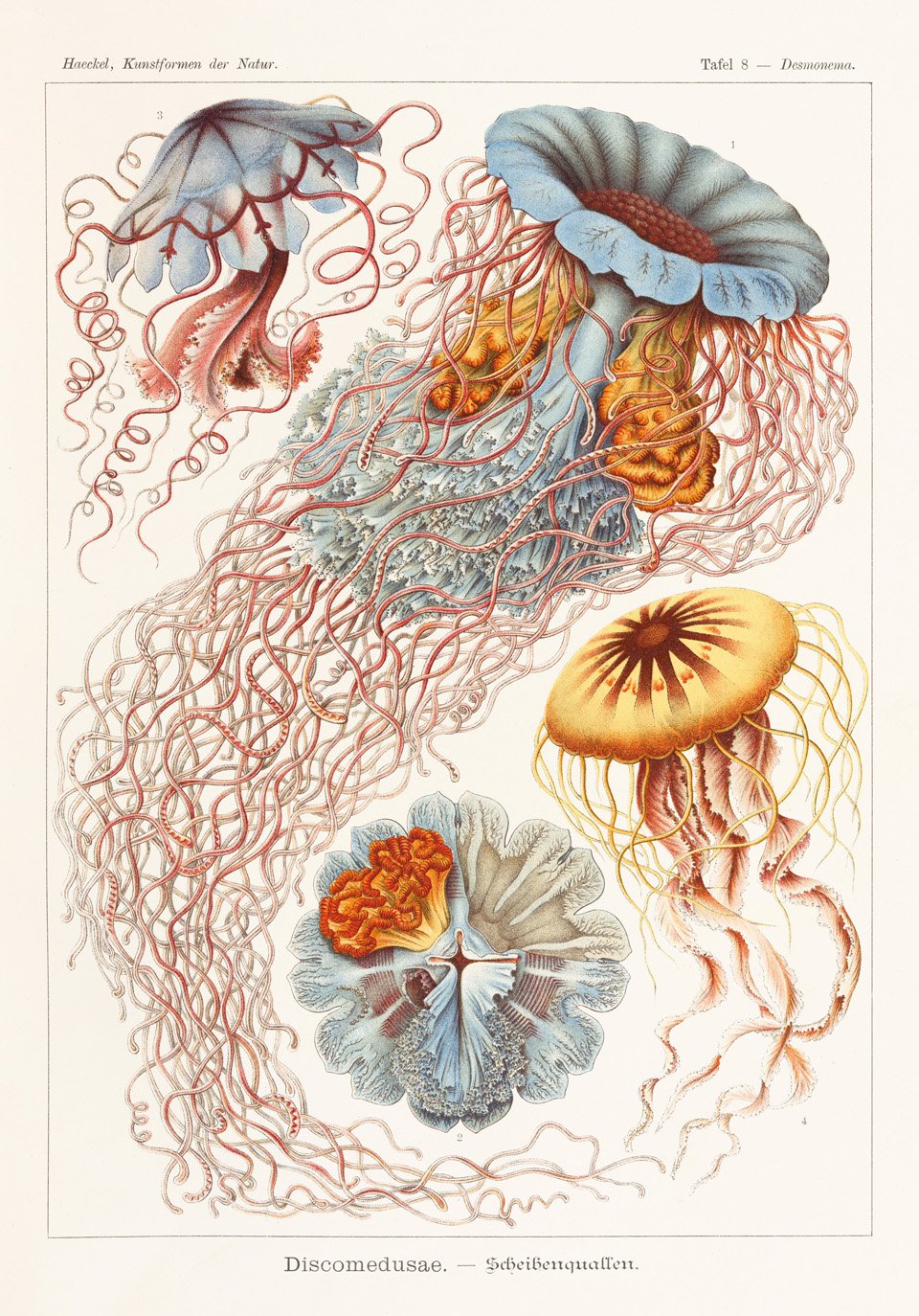

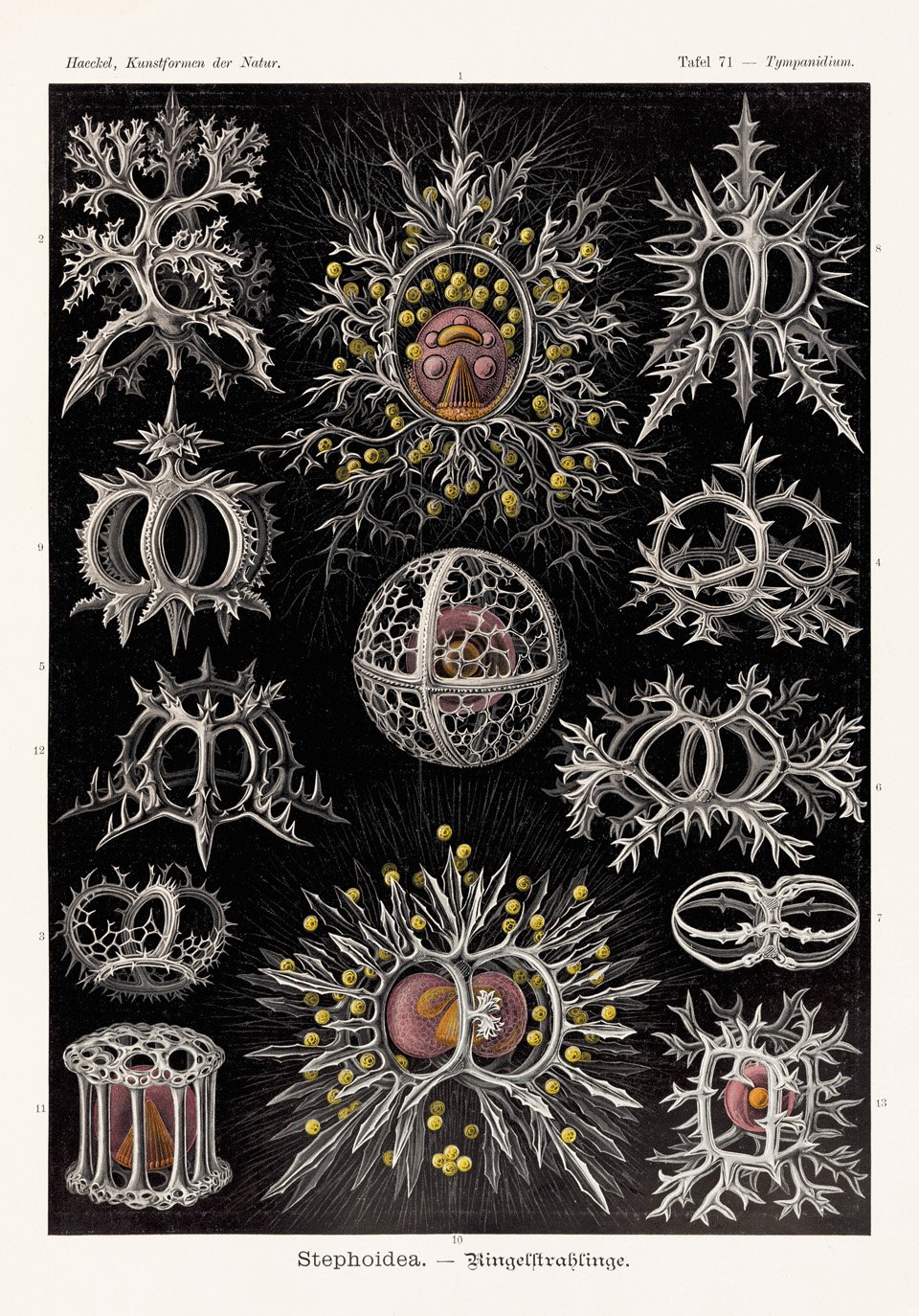

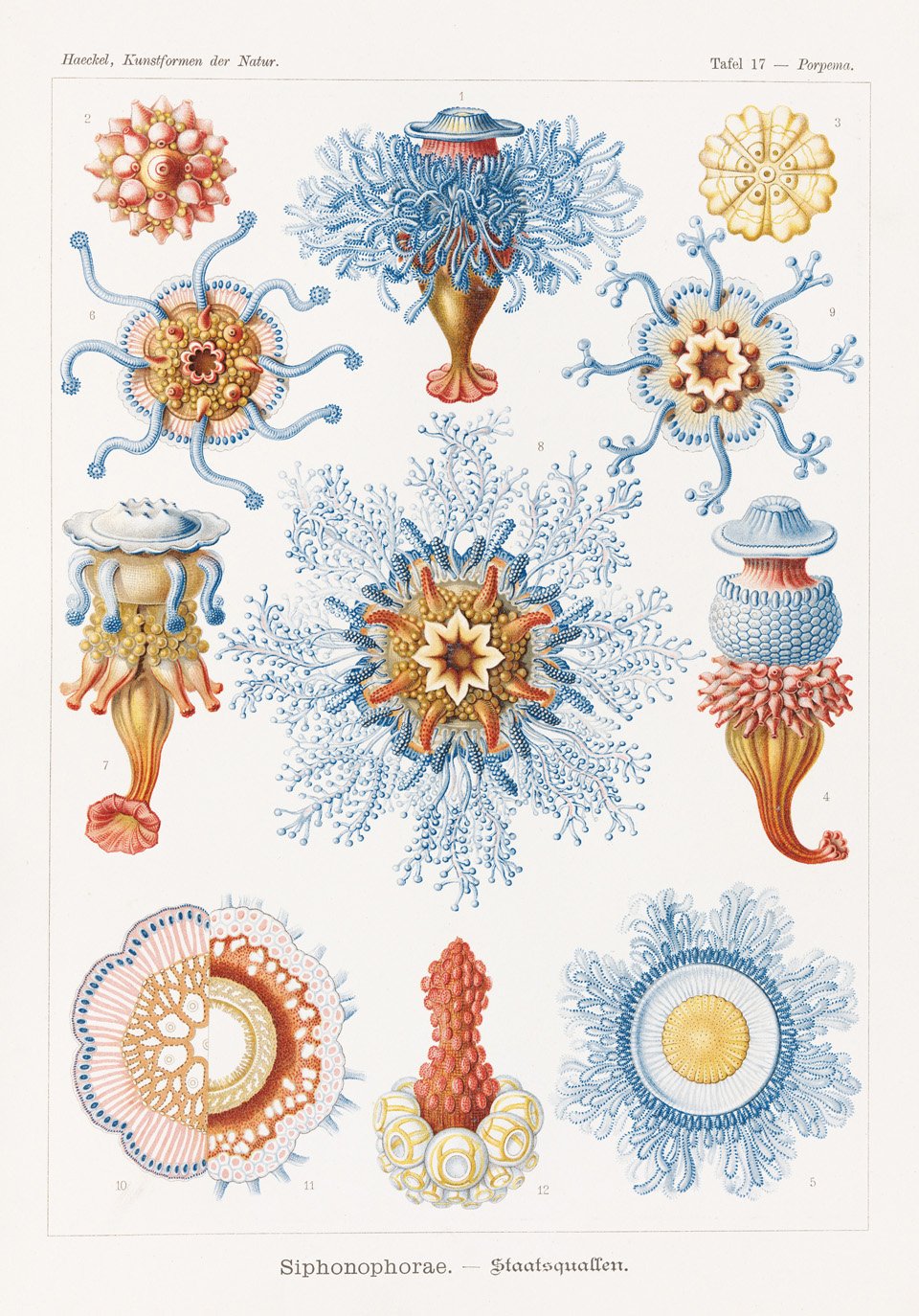

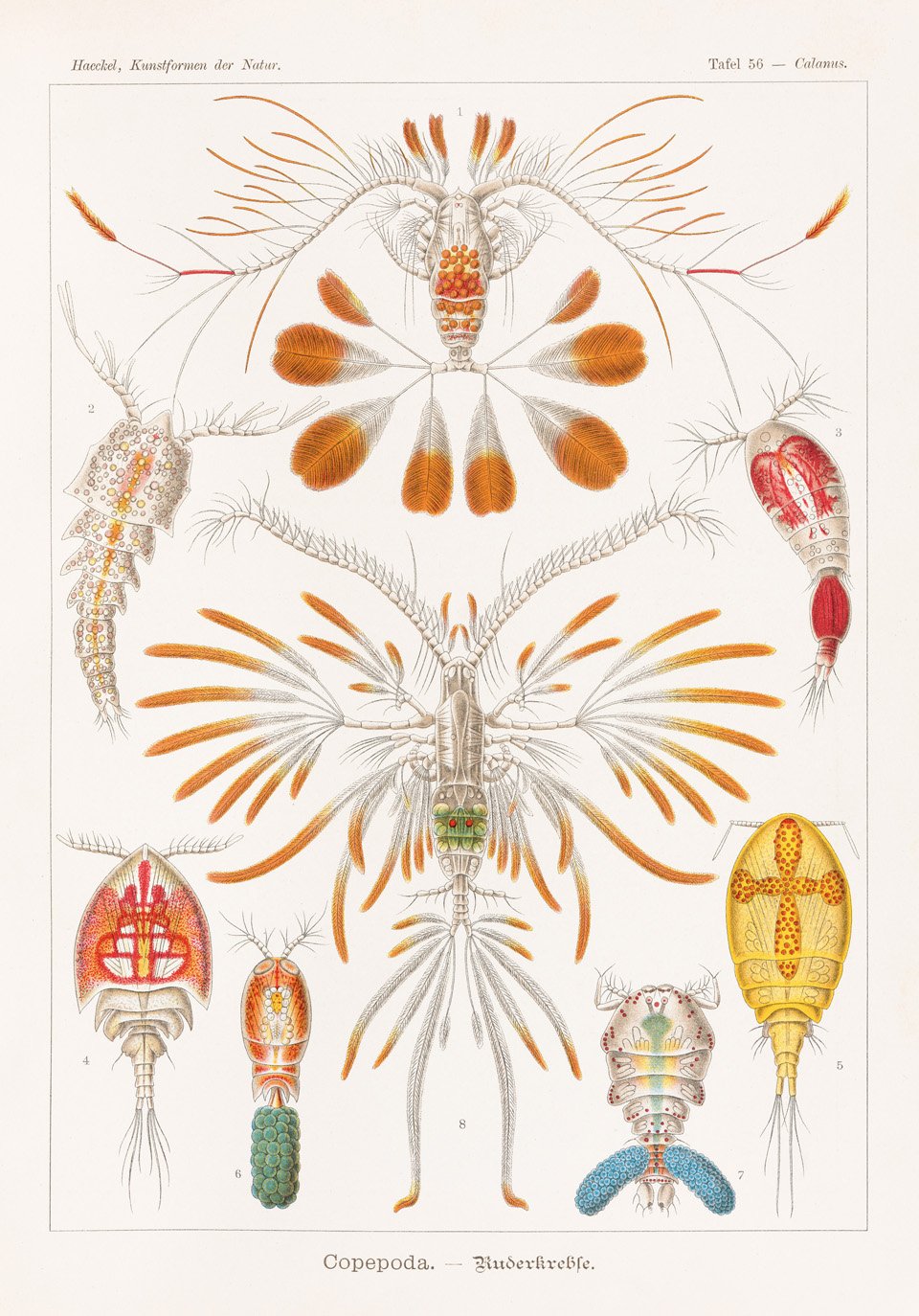

The collection compiles 450 of Haeckel’s most consequential prints of flora and fauna, alongside trilingual commentary by zoologist Rainier Willman and art historian Julia Voss.

Though Haeckel is not a household name outside of evolutionary biology circles, he is one of the most influential minds in science history, having discovered thousands of species, while coining common terms like “ecology,” “phylum,” and “stem cell.”

Best known as a key popularizer of Charles Darwin’s theories for German speakers, Haeckel’s captivating illustrations of life forms—from microscopic sea creatures to primates—helped propagate Darwin’s ideas far beyond an academic audience.

Controversies followed Haeckel throughout his life, and continue to shape his posthumous legacy, but for much different reasons. As a proponent of Darwin’s ideas, Haeckel provoked fierce theological opposition for defending evolutionary theory, and advocating for a biology-driven reinterpretation of human philosophy and purpose.

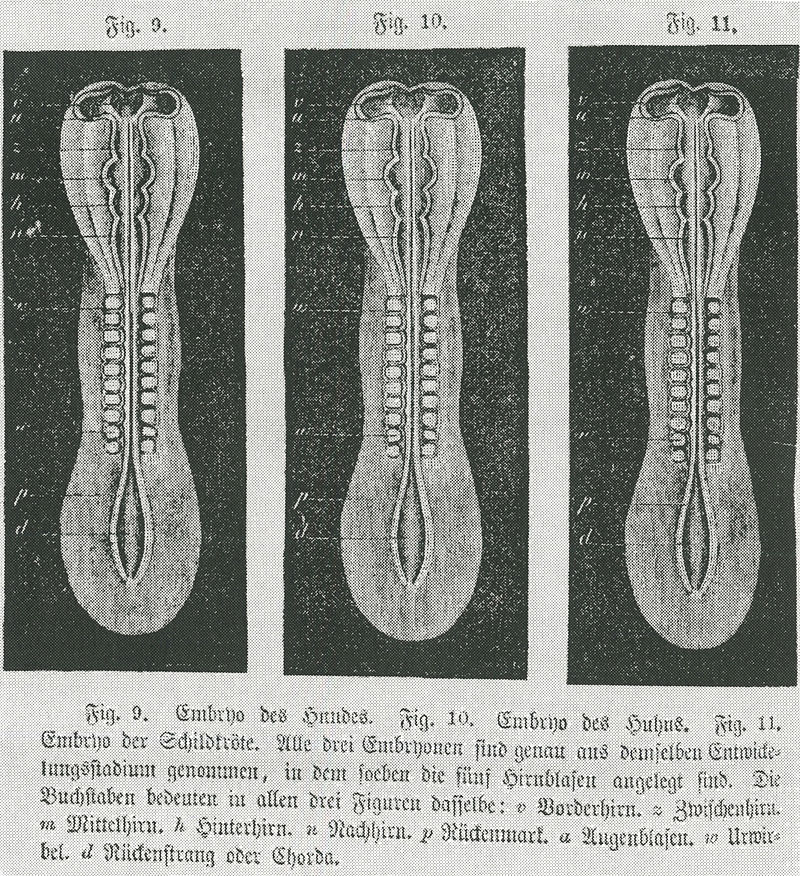

He was also heavily criticized for erroneously passing off the above three woodcuts of embryos as distinct species when they were actually identical copies, a mistake that haunted his reputation for the rest of his career.

Read More: Feast Your Eyes on These Artistic Visions of Earth’s Prehistoric Past

But Haeckel’s most egregious blind spot was his racist interpretations of Darwinian ideas. Calling “woolly haired” people among the “lowest species” of humanity, he claimed they were “incapable of a true inner culture and a higher intellectual development,” according to Willmann and Voss.

Haeckel, who so expertly portrayed the intricate beauty of nature in his volumes of illustrations, could not fully recognize it in his own species. His bigotry underlines the multifaceted social and humanist rifts catalyzed by Darwin’s ideas, which persist to some level even today.

The Art and Science of Ernst Haeckel does not shy away from those controversies, and puts them into the context of the cataclysmic scientific revolution Haeckel and his contemporaries shaped in the late 19th century. The book’s prints and commentary, provided in English, French, and German, shed new light on the prolific output of Ernst Haeckel, and his impact on modern science and philosophy.

Get six of our favorite Motherboard stories every day by signing up for our newsletter.