The ‘Brain-Controlled Factory’ Literally Turns You Into a Cog in the Machine

Credit to Author: Daniel Oberhaus| Date: Tue, 17 Oct 2017 12:30:00 +0000

The ability to effortlessly control the physical world with your mind has long been the purview of science fiction. Thanks to cutting edge brain-computer interfaces (BCIs), however, this fiction may soon be reality. Implanted BCIs have been successfully used by Stanford neuroscientists to restore limb movement in paralyzed patients, off-the-shelf wearable tech allows anyone to type with their mind, and Elon Musk has raised nearly $30 million to build BCIs with his new company, Neuralink.

It’s hard to tell how BCIs will affect the world this early in the game, but the American conceptual artist and self-described “experimental philosopher” Jonathon Keats has a vision of this mind-controlled future—and wants you to become a part of it. Keats calls it Mental Work Industries, and he’s billing it as the world’s first “brain-controlled factory.”

Tucked away in a small room on the campus of l’Ecole Polytechnique Federale de Lausanne (EPFL) in Lausanne, Switzerland, Mental Work Industries turns visitors into futuristic factory workers who control manufacturing processes with their mind.

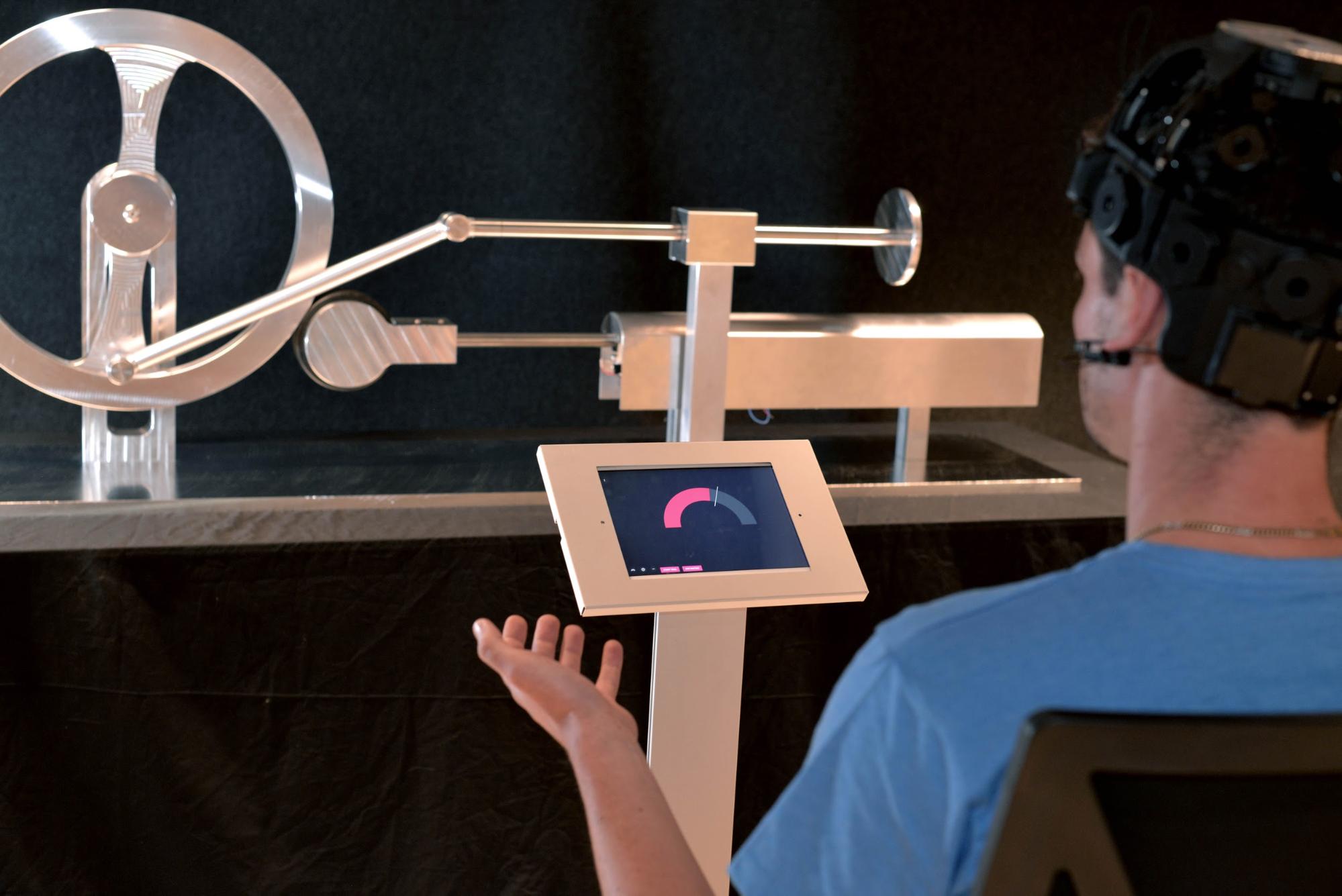

At Mental Work Industries, workers clock in by donning an electroencephalogram (EEG) headset, which uses small nodes attached to their scalps to measure electrical activity in their brains.

“The factory’s brain-computer interfaces will detect neural signals through workers’ skulls,” EPFL neuroscientist José Millan explained in a statement. “Algorithmic analysis of these signals will transform cognitive activity into physical action.”

Workers operate machines using on slider cranks, a mechanical mechanism that converts straight line movement into rotary motion that was a mainstay of the industrial revolution in the 19th century. According to Millan, workers operate the machine by imagining movement in their hands.

Workers will make their way down an assembly line of three brain-controlled machines. The first machine will allow workers to test their mind-control powers by altering the speed of the machine with their mind.

The second station features a similar machine, except this time the algorithm that helped modulate the input from human brainwaves at the first station to make controlling the machine easier is removed. While this theoretically allows the worker to have greater control over this machine, the ability to control it with precision demands greater effort, “possibly greater effort than the human mind can ever achieve,” Keats told me. The point here, Keats said, is to question “whether the operator’s brain is ever really in control, and exposing the power of the interface.”

At the third machine, two different types of BCI are made available to the worker: motor imagery and alpha-wave activity. With motor imagery, the operator has “fully alert control” of the machine, whereas alpha-wave activity (which increases when a mind is in a relaxed state) gives the worker more passive control over the operation of the machine. The type of BCI selected for the worker are based on the how well they have been able to control the machine with their mind.

“Machine III reveals that the interface is not absolute, and suggests that no interface is universally optimal,” Keats said. “An interface is only as good as the degree to which it fits its context, but the right match can be magnificently empowering.”

Although no products will be manufactured using the mind-controlled machines at Mental Work, the data created by visitors as they interact with the machines will be provided to neuroscientists at EPFL, who will use these crowd-sourced brainwaves to further improve BCI technology developed in their labs.

Keats is no stranger to heady science-based art installations. He has made porn for plants, sold real estate in the fourth dimension, created God in a petri dish, and copyrighted his brain, but Mental Work Industries stands out among his projects for its urgency. According to Keats, the project was intended as a way to engage people with an increasingly important dilemma: What will we do when the machines take our jobs? Automation has already gobbled up a huge portion of manufacturing work in the US, and the networked factories of the fourth industrial revolution promise to expedite this process even further.

“In a sense, BCI is the culmination of the cyborg revolution imagined by sci-fi writers in the ’60s: the ultimate amalgamation of human and machine,” Keats told me in an email. “It’s also a compelling alternative to artificial intelligence: Whereas AI strives to make technology omniscient and omnipresent, externally managing our lives without our even noticing it, BCI makes technology a part of us and makes us a part of technology.”

“With AI making headlines as a job-killer, I feel compelled to consider BCI as an alternative path forward,” Keats added.

Mental Work Industries will be housed at EPFL until January, at which point it will begin its journey around the world as an installation in San Francisco and Boston. Keats said it may also be featured in cities in China and India, where the threat of automation is felt viscerally by factory workers.

As Keats’ project demonstrates, there may still be a role for humans in the factories of tomorrow. Hopefully those mind-control workers will actually be getting paid for their brain power, or better yet won’t need money at all.

Gif via YouTube/Skyline Tutorials.