How to Remake Puerto Rico’s Grid to Survive the Next Storm

Credit to Author: Ankita Rao| Date: Mon, 16 Oct 2017 15:00:00 +0000

Benjamin Morales Menendez contributed reporting from Puerto Rico.

Three weeks after Hurricane Maria ravaged Puerto Rico, most of the island is still living in the dark. Hospitals running on spotty generators have no lamps for doctors to look closely at patient wounds. Intersections lack traffic signals to safely guide cars. People can’t rely on air conditioners to temper the year-round heat.

“We have to find the water, we have to queue for everything. We have no choice but to wait for the lord in the heavens and those who are out there—who seem to be doing nothing—to restore the service,” said Ana Barreto, a 63-year-old resident told us at her home in Humacao, an area hit by the center of the storm.

There are plenty of forces to blame here. They include the hurricane—the most powerful storm ever recorded in the Atlantic—and the changing climate. Then there’s the corrupt, debt-ridden Puerto Rico Electric Power Authority (PREPA), which has slowly allowed the power grid infrastructure to deteriorate over the past decades. And the slow response from the US federal government and Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA).

FEMA has a mandate to reconstruct what was lost. And PREPA seems to be following suit. “At the moment we are in a process of removing the deteriorated infrastructure and replacing it with new and operational infrastructure,” Carlos Monroig, a spokesperson for the power authority, told Motherboard.

But restoring the status quo, even with slightly updated materials, would repeat the mistakes of the old power grid: relying too much on imported fossil fuels and depending on one, centralized grid. This will mean, inevitably, another complete, weeks-long blackout next time a storm comes around.

Doing it right, experts told me, would mean investing in diverse sources of energy, especially renewables, and looking into newer systems like microgrids and battery storage. Re-envisioning the grid from scratch could serve not only to sustain the territory, but to build a prototype for future power grids similarly vulnerable to hurricanes, heat, and climate change.

Why Puerto Rico’s Grid Failed

Depending largely on any one source of energy makes for an unstable power grid, especially when these sources can’t be locally sustained, said M.V. Ramana, a nuclear physicist and energy expert at the University of British Columbia. Puerto Rico’s weakness here is that it largely relies on imported fossil fuels, for steep prices, to make electricity.

Before Maria hit on September 20, Puerto Rico was powered mostly by petroleum (about 47 percent). The rest of its energy came from natural gas (34 percent), coal (17 percent), and renewable energy (2 percent), according to the US Energy Information Administration. By comparison, the rest of the US runs on natural gas, coal, nuclear energy, and then around 14 percent renewables. The country as a whole has moved away from using petroleum because of how inefficient and environmentally unsound it can be.

Relying on imported oil has left Puerto Ricans bereft of reliable electricity for years. Even before the hurricane, residents relied on generators during frequent power outages caused by maintenance failures or oil shortages. Puerto Ricans spend almost four times as much on their electricity than the average US citizen, despite consuming less power, since demand for oil is higher than the supply.

Hurricane Maria exposed these shortcomings, as well as latent problems with the island’s already decrepit power lines (which take power from plants to homes) and PREPA’s $3 billion debt. As of last week, the power authority had seen 80 percent of their system decimated—from wires and posts to towers—and lacked the resources to rebuild.

Juan Rosario, an environmentalist who formerly served on the PREPA board, told Motherboard the utility’s efforts to reduce costs threatened maintenance and improvements in the years leading up to the storm. “The hurricane was not going to forgive anything, but the infrastructure which best survived were, for example, the cement poles.”

A Resilient Power Grid Is Diverse

Every expert I spoke to said that to build a resilient power grid, Puerto Rico would need to completely change how it is sourcing its energy. And the best way to do that is by diversifying. When a grid relies on one type of power, any sort of storm or accident can disable the entire network.

“The greater fuel diversity you have, the better,” said Elena Krieger, director of the clean energy program at PSE Healthy Energy, a think tank.

The situation in Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria drives this point home. There has been little access to any sort of fuel since the hurricane. The Guajataca dam was damaged to the point of potential failure in the storm, signaling the threat to hydroelectric power, which comprises one-fifth of its renewable energy. And some solar farms and wind turbines were destroyed on the island.

“This is a total loss,” said Johnny Pimenel, a 63-year-old resident of Naguabo in the eastern part of the island. Standing in the street, he described now the hurricane “ripped off” the blades of nearby wind turbines. “It is a noise I will never forget.”

No one type of energy source is, on its own, failsafe. But there are some that make more sense than others on the island. Wind and solar, for example, are abundantly available if they can be channeled and eventually stored, although long-lasting batteries remain a challenge for this type of renewable. “I would evenly ramp up wind and solar as quickly as possible,” Krieger told me. “I would use that to phase out oil and coal.”

Petroleum and coal are, at this point, too environmentally unsound and shortsighted to invest in, despite President Donald Trump’s obsession with fossil fuels. But natural gas—which emits lower amounts of carbon than other fossil fuels—can still be an option. Even so, renewables make the most sense long-term for Puerto Rico’s energy independence and stability: They rely less on factors like economic stability and importation of fossil fuels (Puerto Rico has no oil or coal of its own).

“If you can instead integrate resources like solar and wind, you can provide a hedge against volatile prices,” Krieger said.

A Resilient Power Grid Is Decentralized

The right mix of energy is only as reliable as the infrastructure that gets it to people. In this case, the energy experts I spoke to all recommended some sort of decentralized power grid that involves microgrids and nanogrids.

Microgrids are just what they sound like—tiny power grids that work independently, even if they are attached to a larger one. These have become increasingly common. In Manhattan, for example, New York University built a microgrid that powers 22 buildings and heats 37. (It’s been operational since 2011.)

The important feature of a microgrid is its ability to “island.” When the larger power grid goes down, this network should be able to continue working. During Hurricane Sandy in 2012, when much of the city experienced a complete blackout for days, NYU’s microgrid stayed powered. Building these sorts of grids—especially ones that power hospitals and universities—could be critical in the face of future disasters.

“The reality is you’re looking at distribution of island ability. If parts of the grid go down, these islands stay up,” said Edwin Cowen, a civil engineer and director at the David R. Atkinson Center for a Sustainable Future at Cornell University.

Nanogrids, meanwhile, are smaller-scale power centers—ones that usually power just a single building—that can run independently with no connection to the larger power grid. Nanogrids usually rely on solar energy, since people can install panels fairly easily. They can run during periods of night or clouds with the use of off-grid battery systems. Hector Santiago, a flower grower in Puerto Rico whose farm is on a nanogrid, was able to keep his property up and running after Hurricane Maria, partly for this reason.

Building a power grid that includes microgrids and nanogrids will be essential to withstanding storms in the future. “We could build a system that’s bulletproof but the costs would be astronomical,” Cowen told me. “If 70 percent [of the grid] can survive a Category 5 hurricane, that’s enough.”

A larger power grid will still be necessary: It’s what often allows energy costs to stay low, by distributing power. “You can then take advantage of energy production in different parts of the country,” Ramana said. Or in this case, on the island.

A Resilient Power Grid Is Smart

Rebuilding Puerto Rico’s power grid now would allow it to capitalize on some of the newer technologies we have developed recently—namely sensors and storage.

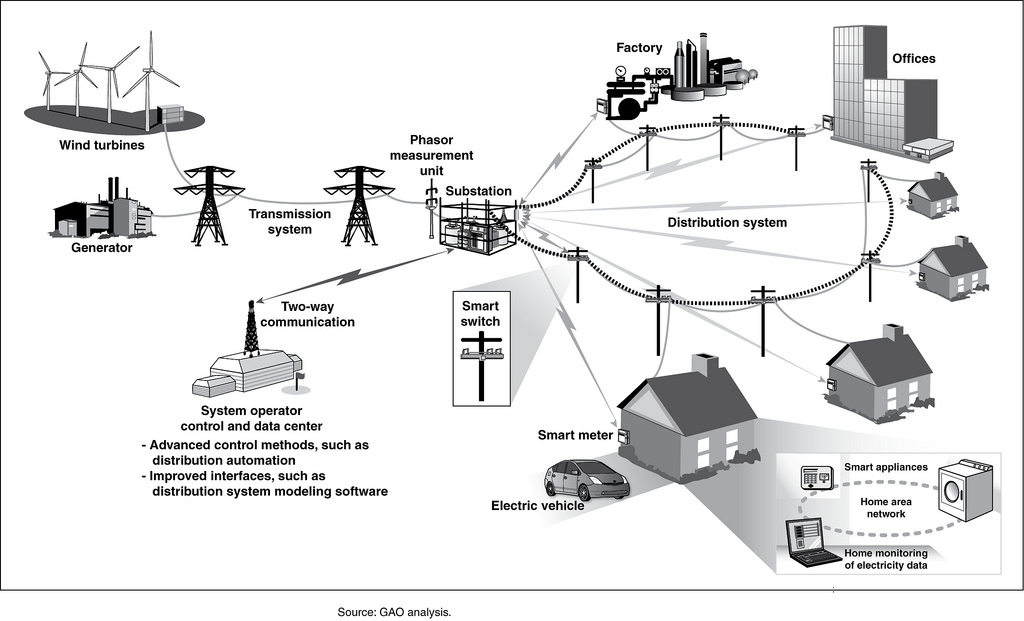

Smart grid technology, as it’s referred to, uses sensors to distribute energy as needed and balance out surplus. It means using smart meters, thermostats, and synchrophasors, which can detect possible energy outages. “It can rapidly detect where energy is being used and can correct and redirect based on that information,” Krieger said.

Puerto Rico had started to implement some smart grid technology already—though its smart meters were reportedly hacked years ago in an attempt to steal power. But incorporating these tools at scale would make for a far more efficient power grid, and help conserve energy across the board.

Meanwhile, the perennial energy storage problem is just starting to prove less daunting. Tesla popularized the Powerwall battery system that allows homeowners to store electricity from both solar panels or the grid. And as Motherboard reported a few months ago, some people are using old computer batteries to make their own power walls to avoid Tesla’s $3000 price tag.

“I’m optimistic, there’s a big difference between Hurricane Sandy and Puerto Rico,” Cowen told me, referencing how far technology has advanced on storage systems in just a few years.

A Resilient Power Grid Requires Independence

The combination of nanogrids and storage presents an opportunity for a totally new kind of energy independence. The ideal set-up requires community-based power grids, and the ability to react and adapt to sudden storms, outages, and other threats.

That could make utilities balk at any of these strategies. LIke some states in the mainland US, Puerto Rico also taxes the citizens who choose to use solar and go off-grid to try and recuperate any financial losses created when people do not purchase state-owned electricity.

“If you’re an individual who wants to run your own home on solar, you’re taxed because you’re not paying for the grid,” said Hector Cordero-Guzman, a professor at Baruch College who has studied Puerto Rico’s economics. “It’s the most perverse incentive system.”

But the market issues can be overcome with different types of regulation. In California, for example, utilities companies have started decoupling, which means they don’t set their rates based on how much energy is consumed, but rather a rate of return, i.e. a profit on an investment over time. That means they don’t make more money when consumers use more energy, and the incentive is efficiency rather than excess.

“Theoretically this transition should not be a threat,” Krieger said.

The cost of renewable energy continues to drop. “We’re getting to the point where solar and wind are becoming cheaper than fossil fuel energy,” Cowen said. “If you didn’t have to worry about grid infrastructure and supporting the debt, we’re below cost parity.”

*

In a recent press conference, Puerto Rico’s Governor Ricardo Rossello said he is looking for a more long-term solution. “That is the critical aspect right now—how does the local government, how does the Army Corps of Engineers, how does FEMA, and how does the private sector help us not only pick up the system the same old way, but how do we make it more resilient?”

Rossello emphasized the role of the private sector in building the new grid, especially since they would afford the island an opportunity to look beyond the restrictions of the federal mandate to rebuild what existed before. He even responded to Elon Musk, when the Tesla CEO offered on Twitter to install solar panels and Tesla Powerwall technology to build a new power grid on the island.

But as people in power debate the best way forward, the residents of Puerto Rico are surviving for the third week largely without electricity, and struggling for even their most basic needs to be met. And despite grand intentions, workers, assisted by the US military and others, are trying to scrap together some part of the failed, and now destroyed, power grid.

“This is so bad that we are recycling, collecting material and replacing what can be saved,” said Juan Baez, a 25-year-old union worker helping to fix power lines. “It’s difficult to know where to start, because everything is very damaged.”

The only real hope for islands like this will be to build a new power grid that takes into account the inevitability of future storms. Whether or not the government, and incoming private sector investors, will treat this trauma as an opportunity to build resilience will decide what happens next.

Get six of our favorite Motherboard stories every day by signing up for our newsletter.