A Hurricane Maria ‘Tech Brigade’ Is Helping Connect the Puerto Rican Diaspora

Credit to Author: Caroline Haskins| Date: Thu, 05 Oct 2017 19:05:00 +0000

A few days after Hurricane Maria ravaged the island of Puerto Rico, the Acupedi pediatrician’s office in Trujillo Alto, a few miles outside of central San Juan, opened its doors for newborns and infants. The office had no power and no water.

Alberto Colón Viera, who lives with his wife in Washington, DC, received a call from his wife’s aunt, who runs the office with her husband. The office’s generators weren’t working, she explained.

“She told me, ‘It’s really hot. We’ve had a lot of babies, and we’ve had newborns, and we’ve had a lot of patients visiting the office,'” Viera told me. “She gave us a bunch of her codes for us to talk to Honeywell, to see if we could override the error code and try to turn them on.”

Viera sent the error codes to the appliance company that produced the generators. Three days later, the company provided override codes it claimed should turn the generators on. Shortly after emailing the codes to the pediatrician’s office, Viera received a reply from his wife’s aunt. They didn’t work.

“That was the last thing I heard from them,” Viera said. “I wasn’t successful, but at least I tried. I don’t know how to measure success, how to characterize success.”

“We are not focusing on traditional relief efforts.”

Viera is one of the members of a group of over 200 coders, computer scientists, and Silicon Valley entrepreneurs calling themselves the Maria Tech Brigade, who believe that relief efforts after Hurricane Maria need to be approached from a different perspective. Namely, by developing technologies for people connected to Puerto Rico.

The Brigade does eventually want to extend these technologies to people in Puerto Rico. For instance, member Jesús Luzon is working on developing low-cost solar panels for people without power. But initiatives like these are in their beginning stages, and the Brigade’s most notable success so far might be its community.

Many members, like Viera, have family in Puerto Rico. Some of them have been able to contact their loved ones, while some have not.

Froilan Izarry, an engineer for code.gov and one of the founders of the Brigade, told me that the group will exist for as long as it’s needed. “We are not focusing on traditional relief efforts,” Izarry said. “We feel that there are numerous efforts led by people with more experience than us that are taking care of this.”

Organizing via Slack and GitHub, the Brigade created a person-finder database with almost 11,500 entries, a ‘Conteca Maria’ SMS tool that uses Twilio, and a website with maps and information for donations and advocacy.

Some members of the Brigade work for tech giants like Google, Facebook, and Amazon, which has its benefits. For instance, one Google employee facilitated access to the Person Finder API, allowing entries to be added in large groups rather than one-by-one.

The Brigade has had some success. Reddit user retrodreamer told me in a private message they were able to use the SMS tool to contact their uncle. “[My family] said they got the message from the site along with my text messages,” retrodreamer said. “They went to a different part of Puerto Rico and were able to get cell service to call me back.”

However, most of Puerto Rico is a telecommunications dead zone. The US territory, home to 3.4 million people, has power available to less than 5 percent of its people and phone service available to less than 40 percent. In essence, most people on this Caribbean island have no way of getting in touch with family and friends in the continental US.

The Brigade isn’t alone in its approach to hurricane relief. Last Friday, Mark Zuckerberg announced that Facebook will be donating ads targeting users in Puerto Rico in order to deliver emergency information.

With some of the world’s best resources at its fingertips, it’s worth addressing the capabilities and limits to online modes of disaster relief.

Why organize online?

Hours before Maria was scheduled to make landfall, Miguel Rios, a senior manager at Twitter, reached out to Froilan Irzarry.

Rios, who was just finishing his paternity leave, knew Irzarry from their work with Startups of Puerto Rico, a nonprofit association that connects Puerto Rican startups and entrepreneurs with one another.

“Froilan and I were talking on Twitter private messages, ‘Hey, we should do something,'” Rios said. “We already had the Startups of Puerto Rico Slack [channel]. We just made a new channel called #maria and said, ‘Hey, we’re gonna organize here. If you have dealt with this kind of response before, or if you just care, have some time for organizing.'”

Before Maria made landfall, the Slack channel only included Rios, Izarry, and a few existing members of the Startups of Puerto Rico Slack. But in the hours after the storm, it became apparent that the storm had had a devastating impact.

Members of the #maria Slack, all based in Washington, DC, tried to organize on-the-ground efforts on Friday, September 22.

Rios knows Carlos Mercander, the Federal Director of the Puerto Rico Federal Affairs Administration (PRFAA), a non-electoral office that works with policy affecting Puerto Rican citizens.

“I sent [Mercander] a Twitter DM saying, ‘Hey, I know you guys have a lot on your plates, I just want to tell you that we’re here to help.’ [Mercander] gave me a call from his DC office—he explained the situation there and what they needed.”

Viera said that they spent the weekend modeling donation data until about 10 or 11 PM each night. On Monday, September 25, the group left their contact information with the PRFAA and offered more assistance if needed. They say they haven’t heard from the PRFAA since.

“We haven’t been on the site,” Viera said. “I wish we could do more.”

The PRFAA’s website provides information for prospective volunteers, but according to Rios, the PRFAA has been overwhelmed with phone calls and emails from people who have not heard from friends and family in Puerto Rico.

In essence, not all help can be accepted.

“There’s about 1.2 million Puerto Ricans in the US, and a lot of them are trying to find their loved ones,” Rios said. “The last time I heard from [the PRFAA], they had received about 100,000 calls, and I can’t image how many emails.”

Tools of the Brigade

While in-person efforts proved to be a dead end, the #maria Slack channel was taking off. Members had been spreading links to join the channel on Facebook and Twitter.

Izarry created a Google Form to organize the group’s skill set, which enabled the Brigade to expand into multiple projects.

One of these projects was Snail-Check, a tool that enables people to confirm when a missing person has been spotted in Puerto Rico, and for family and friends to check if a person has been located.

Snail-Check was authored and managed by Rios. But after being launched on September 22, the tool quickly spread. Person entries have been as high as 500 in a single day, according to Rios. Without the ability to import information in bulk, Rios couldn’t keep up with the entries for the first two days that Snail-Check was live.

In response, a Google employee in the Brigade reached out to their colleagues, and Google offered its People Finder API key on September 24, free of cost. Google’s API allows for person entries to be imported into the database in bulk rather than one-by-one, allowing Snail-Check to accept all valid entries.

“Every once in awhile, we just feel super powerless.”

Rios said that Snail-Check is populated with information from a group of about 60 volunteers, government officials, and shelters in Puerto Rico. These volunteers submit people’s names to the Brigade after verifying their safety.

According to its entries counter, Snail-Check has cataloged the safety of almost 11,500 people as of October 3.

“Now, the [PRFAA] can do other things instead of answering the phone all day,” Rios said. “We created the technology to help without disrupting the operation.”

However, relief crews in Puerto Rico have had notorious difficulty in reaching all parts of the Island. In fact, the military only recently mobilized its tactical hospitals to Puerto Rico. People who live in rural areas inaccessible by roads are less likely to be included in the database than those who live in the San Juan metropolitan area.

Meanwhile, Brigade members Miguel Vacas and Fernando Arocho created a website called Diasporicans, which they describe as a central resource hub for the Puerto Rican diaspora.

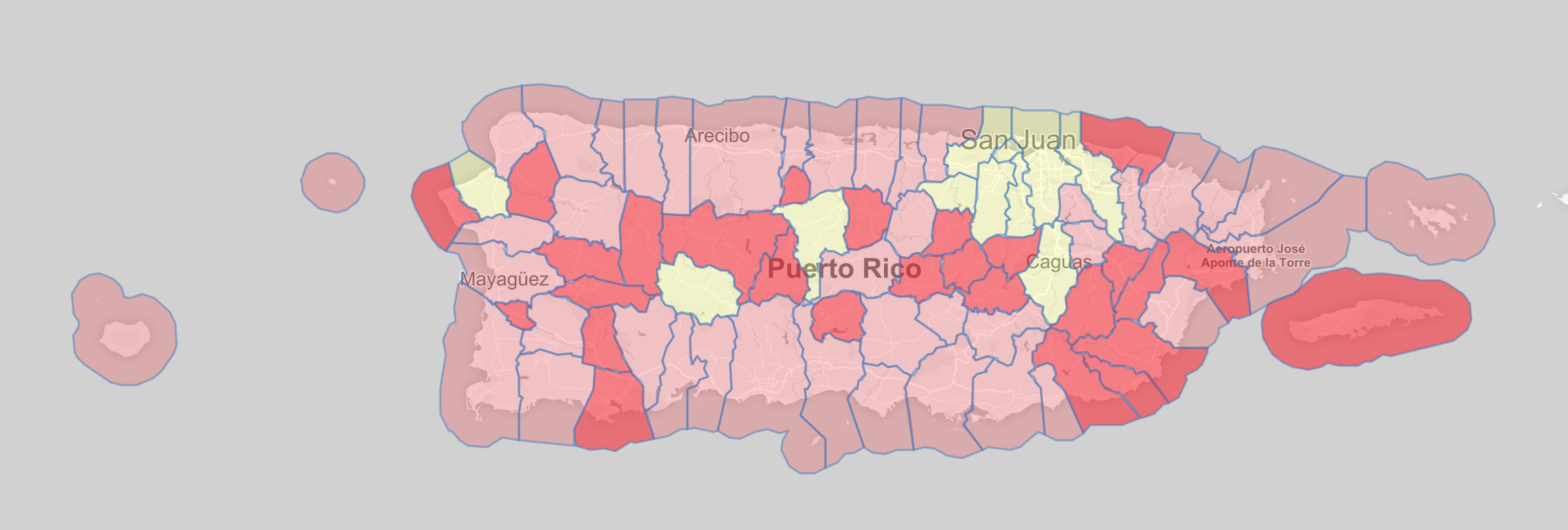

On September 21 Diasporicans went live as an open-source site, meaning it has no concrete ties with a particular group. According to a note on the Diasporicans home page, its relationship with the Brigade is as a “collaborator,” allowing it to feature tools produced by the group like a Puerto Rican map of operating cell towers, the “Conecta Maria” SMS tool, and Snail-Check.

Vacas told me that he constructed a bare-bones version of the website in a feverish six-hour window shortly after Maria blew through, but he was hesitant to publish. Vacas was using a free service from Heroku, a cloud-based hosting service for websites and web apps, but the free service wasn’t equipped for high visitor volumes and could easily crash.

Vacas consulted with Arocho, who suggested to publish the site and prepare it for more visitors later if necessary.

“The website has been continuously iterating,” Vacas said. “When it came out, it was a one-pager. Then when I shared the page with the early group of The Maria Tech Brigade, they started suggesting more and more features to be included—some would give us new maps, others new data to put up.”

In addition to maps of FEMA, USPS, and shelter locations, the current version of Diasporicans also encourages advocacy. There is a permanent link to find your local representative, and on September 28, Vacas also installed a temporary button to tweet #OurHomeNeedsUs, a hashtag designed to pressure FEMA administrator Brock Long to intensify relief efforts.

“We constantly try to remind ourselves what’s our goal here, what’s our angle?” Vacas said. “Do we want to distribute information? Do we want to let people know about the donation centers? People may not agree with us when we did the Twitter button, but that puts pressure on people.”

Vacas said that in seven days, Diasporicans accumulated 21,000 views and began crashing frequently. In response, Arocho redesigned the website, and Heroku donated $250 to provide three months of its professional services for free. According to Vacas, Diasporicans has been running smoothly ever since.

Despite the expansion, the Diasporicans community remains small enough to consider promoting individual cases.

“Not too long ago, late at night, I received a message from a girl who said, ‘Look, I’m using Google [Person] Finder, but my dad isn’t located there,'” Vacas said. “She said, ‘He has arthritis, he has a heart condition, and I can’t get a hold of him. He lives in a part of Puerto Rico that doesn’t have any signal.”

Vacas said that he told her to call the PRFAA hotline. He also said that with her permission, Diasporicans’s Facebook and Twitter accounts could distribute her father’s information. The woman provided permission, and a Twitter user responded with confirmation that the father had been seen safely.

“For us, it’s important for people to feel like they’re getting helped,” Vacas said. “Even even if it’s one person, that’s good enough for me.”

The limits of code

Ultimately, the Brigade highlights the limits to approaching disaster relief with code and information systems. Its members are painfully aware that they are missing a key audience: people currently in Puerto Rico.

“We’re trying to help from here, and we can spend hours writing some code—every once in awhile, we just feel super powerless,” Rios said. “We need to learn when to act and when to wait. Right now, most of what we can do is very constrained by the fact that we just can’t connect with people.”

However, the Brigade represents a community, not just an inventory of talent. According to Izarry, this is most evident when people make contact with family in Puerto Rico.

“There’s a lot of people who have been able to hear from their family members,” Izarry said. “We all celebrate in the channel, and everybody gets rowdy and energized about it because we’re all in the same boat. But some people still don’t know about their family members.”

Izarry and Rios both heard from their families, but the scarcity of gas on Puerto Rico separates conversations over multiple days.

“It’s my Mom’s birthday today, and it’s probably the first one since I have memory that I won’t even be able to say happy birthday to her,” Rios said the day we spoke. “The thing is, that feels like a very small thing given everything else that’s going on.”

Get six of our favorite Motherboard stories every day by signing up for our newsletter.