‘It Made Absolutely No Sense:’ The Story of ‘BMX XXX’

Credit to Author: Blake Hester| Date: Thu, 05 Oct 2017 15:42:20 +0000

Playing BMX XXX is mostly like playing every other action sports game: You ride your bike around a level, do tricks, and score as many combos as possible. In the early 2000s, this was nothing new. Thanks to the popularity of Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater, action sports games were the thing. The only difference is, in BMX XXX, game characters are not famous BMX pros, they’re sometimes naked women.

In addition to pulling off tricks, players do things like helping a constipated construction worker get “the poop loose,” or listen to a horny Mormon missionary talk about how much he wants to go down on a giant inflatable woman. If they play their cards right, they might get rewarded with a live action video of a woman stripping to 311’s “Down.”

Today, it’s hard to imagine how a video game like BMX XXX would get pitched, approved, funded, and developed for months, without someone involved stopping for a second and saying, “Hey, this might be a dumb, offensive idea.” It’s even harder to imagine a large game publisher would think it was a good idea to funnel millions of dollars into. It’s almost impossible to believe it not only came out, but came out uncensored on Nintendo’s GameCube.

But it happened. BMX XXX is a real video game that was published in 2002 for the PlayStation 2, Xbox, and GameCube, and it was a complete disaster. It was a game that made nobody happy.

Leading up to its release, the game had a ton of buzz, even being covered by The New York Times and Playboy , something pretty rare in the early 2000s. However, the buzz wasn’t particularly good. Taking influence from TV shows like Jackass, the game included humping dogs, foul language, and naked women, both animated and real. Somewhere underneath it all was a solid BMX game, but by the time the press was out there, it never stood a chance.

Due to its heavily publicized nude scenes, involving real women thanks to a partnership with the New York stripclub Scores, BMX XXX was banned from outlets like Wal-Mart and Toys”R”Us, juggernauts in the pre-Amazon, pre-digital storefront era. Coupled with no pro-athlete support, when it released it sold barely over 160,000 total copies across all platforms, according to numbers provided to Motherboard by the game’s producer.

The story of BMX XXX is a story of a publisher going too far. It’s a story of a lot of people thinking they know what’s best, and learning the hard way—and at the cost of millions of dollars—they’re wrong. It’s a product of a time largely devoid of non-objectified female characters in video games, when the game industry was, even more so than now, a complete boy’s club.

BMX XXX exists as a look back at a time when the conversation around representation of women in games was far different than it is today, when Lara Croft was still highly-sexualized and before games like Life Is Strange explored what it was like to be a young teenage girl. It was a weird experiment to see if it was possible to make an adult humor game, a test to see just how far a developer and publisher could push the envelope.

To understand what happened, we tracked down a handful of developers and people on the publishing side to figure out how this game came to be and who thought it was a good idea.

The short answer, as executive producer at the now-defunct New York-based video game publisher Acclaim Shawn Rosen tells it, came from a simple joke told in a meeting.

“You know, when you get a whole bunch of guys in a room, people start throwing out stupid ideas,” he told me. “So we’re talking about, ‘Okay, maybe we should go [for a Mature rating]. What does Mature mean? Maybe we’ll have some more hardcore music, maybe there’ll be a little bit more language in it.’ And someone threw out, I don’t remember who it was, ‘Let’s put strippers in the game.’ And everyone laughed.”

How it started

The story of BMX XXX starts, appropriately enough, in a bike shop. Rosen was trying to buy a bike for his son when a video caught his eye. Playing at the store was the BMX tape Expendable Youth, featuring pro riders such as Joe Rich, Chad Kagy, and someone who would become a big part of Rosen’s life, the late Dave Mirra.

For Rosen, someone who grew up riding BMX bikes and building ramps in the park next to his Long Island home, BMX seemed like the perfect fit for a video game. He went home and began writing his pitch.

When he presented his idea to the higher-ups at Acclaim, he told me in a phone interview, they loved it. The publisher looked to its internal developers to see who could take on the project. Rosen wasn’t particularly excited about this route because, as he said, “none of them were very good.”

At the same time, on the other side of the country in the Bay Area, independent developer Z-Axis was making a small splash with its own extreme sports games. In 1999, it released Thrasher Presents Skate and Destroy, an officially licensed game that took a more realistic approach to its controls than Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater, which launched just a month earlier in August 1999.

Rosen pitched his idea to Z-Axis, which was into the project. The company thought it could make a 3D model of a bike, put a character on it, drop it into one of the Thrasher levels and have a prototype working relatively soon.

“They did it in, like, a day and sent a build back to me. I presented it to executives at Acclaim and they loved it,” Rosen said.

Z-Axis got to work on a BMX game. The only thing Acclaim was missing was a professional, famous BMX rider that could bring brand recognition. It would find its answer in two riders: Dave Mirra and Ryan Nyquist.

“We flew out to meet with them. Dave was in love with the idea and Ryan basically mirrored everything that Dave did. So, if Dave said, ‘Let’s do this,’ Ryan followed,” Rosen said.

Mirra got other professional riders and sponsors on board. He helped design the move list and did motion capture for the game, allowing for his real-world tricks to be digitally reproduced. Every step of the way, Mirra helped make this new game which would bear his name.

“[I] remember looking at people like, ‘What? We’re going to do what?’ It was completely baffling.”

The collaboration between Acclaim, Z-Axis, and Dave Mirra resulted in Dave Mirra Freestyle BMX, released for the PlayStation, Sega Dreamcast, and PC on September 26, 2000. It released to relatively good reviews and was popular enough to warrant a sequel released on the PlayStation 2 in August 2001, and GameCube and Xbox in November of the same year. Concrete numbers aren’t easy to find, but based on online estimates and numbers given to Motherboard by former Z-Axis employees, both games have sold between 800,000 and one million copies to date across all platforms.

Freestyle BMX and its sequel couldn’t have come out in a better era. Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater, Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater 2, and Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater 3 not only helped revitalize the skateboard industry, they created a phenomenon. The series inspired dozens of knock-offs; Surfing, rollerblading, and, of course, BMX games all started hitting the shelves, trying to cash in on this new industry.

Try as they might, none were as popular as Tony Hawk, a series that looked like it couldn’t be stopped. Higher-ups at Acclaim, now two games deep into its Dave Mirra series, had eyes on the success of its competitor. Acclaim knew it could never be number 1, but, as Rosen said, it wanted to be number 2. Acclaim thought it had a winning formula; all it had to do was keep making Dave Mirra games.

“Stupid ideas”

Around 2001, Z-Axis felt it wasn’t enough just to ride around a level scoring points. The developer wanted to add a story, voice acting, and missions—something the Tony Hawk series would adopt years later. Z-Axis was, for the time being, ahead of the curve.

“I’m pretty sure that it was kind of laid out that [the player was part of] a BMX team on tour, and we were just stopping along our tour route throughout the states,” Z-Axis lead artist Mark Girouard said. “You know, a lot like the skate videos you’ve seen for decades now [where they] just get in their beat-up car, drive, stop at some abandoned amusement park and go skate.”

The developer was excited for the new game it was making. Z-Axis loved the Dave Mirra series—former developers I talked to still speak highly of it—and the third iteration was a chance for it to really expand the tech it’d been developing for the past couple of years.

“We were making this awesome game, we were totally proud of it. Plus as developers we were pushing the boundaries for ourselves,” Girouard said. “It was going really well.”

Then Acclaim got involved.

As the action sports genre kept getting bigger, it was getting a little crowded. Activision had published branded video games starring pro surfer Kelly Slater, BMX pro Matt Hoffman, and wakeboarder Shaun Murray. Weirder yet were paintball video games like the Extreme Paintbrawl series and even a PowerBar-sponsored mountain climbing game called Extreme Rock Climbing. Most of the latter received reviews ranging from “bad” to “abysmal.”

Acclaim executives wondered, what could they do to get people talking again? This was the question higher-ups at Acclaim and Z-Axis were asking themselves in the meeting where the fateful joke was told: “Let’s put strippers in the game.”

“For an extreme sports game, I gotta be honest, it made absolutely no sense.”

The idea of adding strippers to the game made everyone laugh. It was ridiculous. But, surprisingly, when everyone stopped laughing, serious conversations began. “It was suddenly like we were working on a concept for a mature video game,” Rosen said. These concepts would slowly become a new take for the Dave Mirra franchise. Acclaim hoped appealing to an older audience would yield bigger sales, which, Acclaim marketing coordinator Zach Smith told me in a phone interview, the company needed badly.

“Acclaim was in dire straits: They really needed the game to do well. I think that was a main driver behind the decision to put nudity into the game. ‘This is something that’s going to get a lot of PR, good or bad, no matter what we do,'” Smith said, speculating the thought process of his bosses at the time.

“In that context, it definitely was a viable option for Acclaim,” he said. “The best option would be to make a great game, but as Acclaim [would] do, they came up with this option. Acclaim definitely made lots of questionable decisions to get PR.”

Adrienne Shaw, an assistant professor in Temple University’s Department of Media Studies and Production and founder of the LGBTQ Game Archive, told me in an email interview she thinks whenever the industry is struggling, developers will often push for offensive content rather than progressive to combat flagging sales. “[If] a company thinks the best way to make money is ‘going there’ then they’ll ‘go there,'” she said.

In the publisher’s eye, “going there” meant a more mature game full of nudity. It meant sex jokes and raunchy, offensive dialogue. It looked to sex comedies and Jackass for inspiration. This, to Acclaim, was the way to get people talking. Employees at Z-Axis weren’t as sold as their bosses. Some were even angered by this new direction.

“That had to be the biggest creative shock I’ve ever experienced in games through all these years,” Girouard said. “We were all in a meeting, it was probably four or five people at most. [I] remember looking at people like, ‘What? We’re going to do what?’ It was completely baffling.”

Even more surprising for the developer was a strange partnership with the strip club Scores to include unlockable videos of real women stripping.

“That just showed up one day for us,” lead designer Tin Guerrero said. “‘Hey, by the way, we got the license to use Scores.’ At that time, the early 2000s, Howard Stern was really big and I guess, from what I understand, that was his favorite strip club or something. So to New York-based Acclaim, they were like, ‘Cool. Scores is going to be huge.’ But I don’t think anybody else in the rest of the world—except for I guess Howard Stern listeners—knew what Scores was.”

Rosen takes responsibility for the Scores idea. Call it a premonition, but he said he had a feeling if he approached the club about the game, it would be into it. Which it was. Striking a deal, Acclaim would pick which women it wanted in the game, and then it would film them at the club taking their clothes off. These would be in-game rewards for players pulling off a set number of objectives.

Rosen sighed.

“For an extreme sports game, I gotta be honest, it made absolutely no sense,” he said. “But it was an interesting idea and the amount of people that were talking about it, the amount of people that were excited about it really surprised us.”

At the time, the Grand Theft Auto series was selling millions of units. It was offensive, violent and, most importantly, rated “M” for a mature audience by the Entertainment Software Rating Board, the self-regulatory organization that assigns age and content ratings to video games. In other words, it was just the catalyst Acclaim needed to get behind its own adult-oriented game. “It showed us, ‘Alright, if we do this the right way, we could actually sell some big numbers and get some pretty big hype on it,'” Rosen said.

With Acclaim set on this new direction, Z-Axis redesigned major parts of the content it had made thus far, changing what would’ve been Dave Mirra Freestyle BMX 3 into what became known as Dave Mirra BMX XXX.

“I probably was pissed off because I knew we were going to have to scramble and redesign the game,” Girouard said. “Acclaim gave us a little more time, but it was definitely not enough to compensate for having to go back and redesign an enormous amount of content.”

Employees at Z-Axis didn’t have a choice. Its management not only agreed to the idea, but seemed to think it was a good one. Furthermore, Z-Axis had signed a multi-game deal with Acclaim back when it signed on for the first Dave Mirra. It was contractually obligated to make what the publisher wanted.

“One thing that is a common misconception in the game industry itself is that if an independent developer makes a game, then it’s their idea, they stand behind it, they believe in all the content. They’re making it for themselves. No. We were paid by Acclaim to make BMX XXX. As much as people think that the people at Z-Axis were crazy for coming up with this idea, we were contracted to make this idea,” Guerrero said.

It was a frustrating situation for the developer, but no one I talked to necessarily speaks badly of the time—just of the circumstances. Even though Z-Axis was contractually obliged to make a game it didn’t understand, the former employees I talked to said they were never going to just phone it in. They still wanted to make the best game they could.

As they tell it, Z-Axis was like a family. They were a young group tucked way away in Hayward, California, making games and having fun. They’d ride BMX bikes around their office, put holes in the walls, cook big dinners for everyone and watch episodes of Futurama. The office had beds and showers if people needed to stay late or overnight. Producer Glen Egan spent two whole weeks at the office without going home.

“That was pre-marriage and kids,” he said.

Surrounded only by an industrial park and an airport, Z-Axis employees could basically do whatever they wanted at night with no supervision around. They would hit golf balls at the adjacent park or blow up CRT TVs with M-80 fireworks in the parking lot.

The developers were having fun, they were making a game with mechanics they believed in, and jokes they thought were funny. There was no way to predict the storm coming for them.

Like nails in a coffin

If you put yourself in the mindset of a video game publisher in the early 2000s, these ideas almost make sense. In fact, they sound like a recipe for success.

At this time—even more so than now—video games were marketed to horny young men. You couldn’t open a magazine without seeing sexual innuendo or polygonal women straddling each other. Acclaim thought this meant games were ready to take the jump into adult-oriented humor.

“We cut and edited [a trailer] all night long and by that morning we sent it out to all the executives and the whole company went nuts,” Rosen said. “I think the next day we released it online. You never saw such a big response for a game as what we released. We followed it up with a second trailer which was good. It wasn’t as good as the first one, but they both had such a huge impact that all the sudden we were getting magazine covers all over the place.”

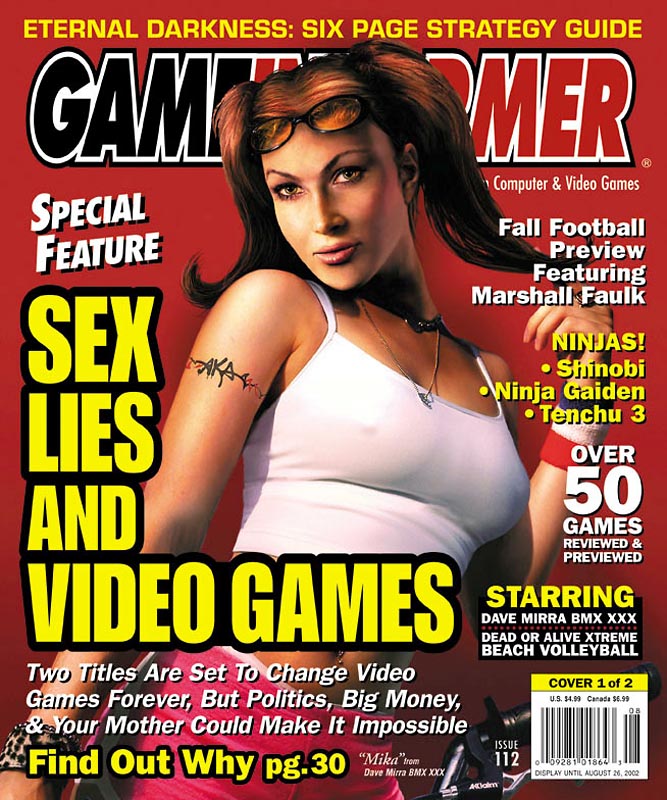

Game Informer and IGN Unplugged put BMX XXX on its cover. To supplement this attention, Acclaim launched an aggressive ad campaign, featuring irreverent jokes and the tagline “This is BMX?” The game’s website boasted a game full of “pimps, puke, bitches, hoes, strippers, constipation,” and other ridiculous stuff like “dogs who love to hump.” It ran a competition to find a “Miss BMX XXX.” And it, of course, touted loud, proud, and clear the game would have breasts. Z-Axis had no other choice but to watch as the game it was working on slowly became “the stripper game.”

“As a gamer myself, I definitely thought it was something you wouldn’t typically see in a game; I knew that it would make this game stand out,” Smith said. “But I didn’t really think about the more ethical points of having nudity in games as a 24-year-old.”

Shaw said that in the 90s, games were often marketed based on which gender they would appeal to, rather than trying to appeal to both. “It was also assumed that the way to get girls and women to play was to represent women better—but only in games for women. Both points left out that women already played games and that the problem of representation isn’t just so marginalized groups see themselves represented well. Taking the BMX XXX example, they probably told themselves their target market was an audience who would like this type of representation of women. They never considered whether they should cater to that market in that way.”

Guerrero said that the marketing decisions were completely out of the developer’s hands at that point. “We had no input or say in how they marketed it, where they marketed it, how they dealt with the controversies, and how they did or did not piss off Wal-Mart and stuff like that,” he said.

Read More: Fuck You And Die: An Oral History of Something Awful

“It had such momentum, we thought we were going to sell millions of units. There was so much hype about that game that we thought it was just going to be the next best thing,” Rosen said.

It wasn’t.

In May 2002 the first impressions of Dave Mirra BMX XXX started coming out after it was shown off at E3, the industry’s huge, annual conference. The video game website IGN said it was “A surprise in every sense of the word, any title that’s working hard to perfect ‘Boob-Jiggle Technology’ deserves a questionable double take.” IGN ended up awarding it the unofficial “Most F’d Up Idea Award”—an idea that tickled Egan so much he made the team coffee mugs brandishing the title.

It took only a few months after that for everything to fall apart.

“I flew out to Dave’s house to present the game to him,” Rosen said. “I pitched the game to him and he was rolling on the floor, he thought it was the funniest thing ever. He was onboard, he was 100 percent on board. We left his house, [I] came back thinking, ‘Everything is great, Dave’s signed on, we’re going to do this.’ And then all his sponsors came back saying, ‘Don’t even think about it. This will hurt your image in a way that you’ll never be able to bounce back from.'”

And, Rosen admits, they weren’t wrong.

The first nail in the coffin for Dave Mirra BMX XXX was when the pros pulled their support. All popular sports games rely on pro support to sell copies. The long-running NFL Madden and NBA 2K series pay top athletes millions of dollars to appear on the covers of their annual games. The Dave Mirra Freestyle BMX series obviously had Dave Mirra. Tony Hawk games had Tony Hawk. In this genre, brand recognition is everything. A casual game consumer is far more likely to pick up a game if they see something or someone they’re already familiar with on the cover.

But when it came down to the content, professional riders risked losing sponsorships—which pay their bills—by being involved. It was a liability to their careers. One by one, they all started dropping their support. This included Mirra himself, who pulled his name from the game. Acclaim shortened the title to simply BMX XXX.

“Without having him, I think it lost a whole chunk of its identity,” Egan said.

Mirra would go on to sue Acclaim in 2003 for $20 million, claiming he didn’t know the game would be taking the direction it did—a claim Rosen disputed. “It wasn’t true at all. I flew to his house and we went over it together. So he was fully aware,” he said. Mirra ultimately dropped the lawsuit, agreeing to work with the company again, though the two never partnered for another game.

By October, the second nail came when major retailers like Wal-Mart and Toys”R”Us announced they wouldn’t be carrying the game. This was a death sentence. In 2002, the year the game released, Wal-Mart alone sold 25 percent of all video games purchased in the United States. Believing its title was sure to be a massive success, Acclaim didn’t prepare well for when retailers denied carrying it.

Z-Axis and Acclaim were stuck working on a game they knew was being sent out to die. To get the game sold in Australia—which had initially banned it—all sexual content had to be removed . Sony required the nudity to be censored on the PlayStation 2. Ironically, despite its family-friendly image, the game was released uncensored on Nintendo’s GameCube, which, according to some people we talked to, wasn’t doing well at the time and saw—like Acclaim—an M-rated game as a way to score additional sales.

“It was like, ‘Well, I guess this isn’t going to do very well. But we’re going to keep doing what we do and try to make the best thing we can,'” Egan said.

There was one stroke of luck: Z-Axis was purchased by Activision during development. It would move on to new projects and this would be the last BMX game it ever worked on. Wanting to distance themselves from the project and its controversies, Guerrero said some developers at the studio decided not to put their names in the credits, choosing instead to abbreviate their last names or use the names of historical figures, like Fletcher Christian.

Over at Acclaim, it was like people were running around with their hair on fire.

“Acclaim didn’t have a lot of money at that time, so spending the kind of money that they spent on marketing, they really thought that it was going to be huge,” Rosen said. “It hit hard on a lot of fronts when it didn’t take off.”

Rosen’s wife pipes in from the background of our call: “We went from dreaming of champagne to drinking Natty Light,” she said. “We were like, ‘This is going to be it! We’re going to make so much money!'”

“Yeah, none of that happened,” Rosen said.

Barely in stores, estranged from its pro support, BMX XXX was a spectacular flop when it released in November 2002. Reviewers panned its content and the game sold abysmally. As of December 2005—the only data I was able to get my hands on, provided by Egan—the game had sold barely over 160,000 total copies, making just shy of $5 million in its lifetime. For comparison, the top game that year, Madden NFL 05, sold more than 770,000 copies, making more than $26 million, in December 2005 alone.

“If you look at things like Jackass and stuff like that, they’re always trying to be funnily offensive,” Egan said. “But every now and then somebody pushes that over the line. I think the [live action videos], especially, just pushed it all over the line. And then it all unraveled from there.”

Rosen left Acclaim soon after the release. A couple years later, in 2004, the publisher filed for bankruptcy. Z-Axis went on to develop X-Men: The Official Game and helped out on the Guitar Hero series.

“Sex sells, but nobody wants to touch it,” Rosen said. “It’s that same kind of thing where they have the Playboy magazine at the top of the rack, but you don’t want anyone to see you grabbing it.”

How bad it can get

These days, BMX XXX is a distant memory for the developers I interviewed. A lot of them were surprised anyone remembered the game, and some were especially surprised someone wanted to talk to them about it.

Egan and Guerrero both work for developer Sanzaru Games, which develops more family-friendly titles such as Sonic Boom: Fire & Ice and Sly Cooper: Thieves In Time. Mark Girouard now teaches game design at the Academy of Art University in San Francisco and works as an independent developer. Zach Smith is still in the industry, working for a media agency specializing in buying advertising for gaming clients. Rosen took a completely different path in life and now owns his own koi pond business. Mirra took his life in February 2016 while visiting friends in Greenville, North Carolina. He was 41.

Their joint creation, BMX XXX, has never really gone away, though. It’s earned a cult status in the game world, one you remember hearing about as a kid, or a game you’d sneak a peek at in a GameStop when no one was looking.

But, for others, BMX XXX simply going as far as it did wasn’t some huge accomplishment.

” Birth of a Nation was an important part of film history, I think that’s pretty well established,” Shaw said, referring to D.W. Griffith’s 1915 racist film about the Civil War and the birth of the Ku Klux Klan. “Its technical importance though lives outside its content, I think. If there were a similar film, that had all the same technical firsts, but it was about the Haitian Revolution, I can’t help thinking we’d all be better for that. I don’t think we need examples of ‘how bad it can get’ to imagine better futures.”

Born in a room of young guys throwing out “stupid ideas,” BMX XXX is a look back at a time when video games and the industry producing them lacked any female representation and an example of not being able to read the room. It’s a game, it turns out, no one wanted. No matter how hard Acclaim told them they did.

“I mean, nowhere in extreme sports does that ever cross paths,” Rosen said. “So it really made no sense, but we actually made it work. The game was fun to play and—”

Rosen’s wife interrupted him.

“There were boobs,” she said.

Get six of our favorite Motherboard stories every day by signing up for our newsletter.