FOIA: How Police Convinced the FAA to Put a No Fly Zone Over Standing Rock

Credit to Author: Jason Koebler & Sarah Emerson| Date: Wed, 27 Sep 2017 14:30:00 +0000

When last year’s Dakota Access pipeline (DAPL) protests came to a head, disturbing footage shot by Indigenous drone pilots revealed the extreme brutality of Morton County police.

Using drones, peaceful demonstrators, also called “water protectors,” filmed an armored vehicle launching percussion grenades into the crowd; water cannons being fired at civilians; and continued pipeline construction after dark. Their footage helped to expose the military-style tactics used by local law enforcement to suppress dissent—excessive force that is now the subject of a class-action lawsuit filed against Morton County by on behalf of those injured at the Standing Rock protest camp.

At the behest of law enforcement working in the area, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) imposed a temporary flight restriction (TFR) over Standing Rock within a four-mile radius. The restriction applied only to civilians, and was criticized by freedom of speech experts who said the TFR may have violated First Amendment rights of journalists flying in the area.

Motherboard obtained nearly 100 pages of emails between the FAA and federal, state, and local officials, detailing their attempts to misrepresent demonstrators as violent criminals to obtain extended flight restrictions. These documents were provided to us through a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request submitted to the FAA in October of last year.

Many of the emails from law enforcement to the FAA attempt to paint demonstrators as violent; one email from Michael Link, director of North Dakota State Radio—a communications system that’s part of the North Dakota Department of Emergency Services—requesting a TFR from the FAA noted that the “protest has become violent with protesters organizing and deploying in paramilitary style actions.” Throughout the 98 pages, law enforcement on the ground describes the situation in much the same way one would describe a war zone. It’s worth noting that incidents of violence by law enforcement far outnumber any that could be connected to demonstrators.

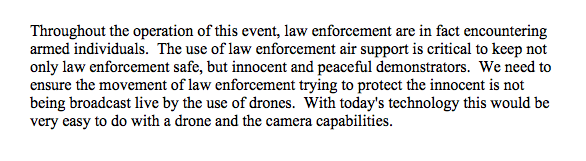

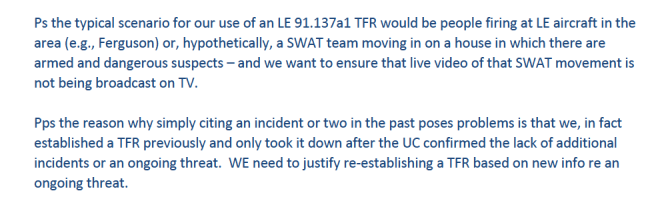

“We need to ensure the movement of law enforcement trying to protect the innocent is not being broadcast live by the use of drones. With today’s technology this would be very easy to do with a drone and the camera capabilities,” wrote North Dakota Highway Patrol Sgt. Shannon Henke to North Dakota’s Department of Emergency Services (DES).

The FAA issued the TFR ostensibly because law enforcement officers on the ground were telling the agency that drones presented a persistent threat to police helicopters and police on the ground. However, several of the events cited in emails to the FAA did not occur as described, and an Indigenous journalist who was arrested for flying drones at Standing Rock was later exonerated based on video evidence he presented in court.

When journalist Aaron Turgeon was arrested by Morton County Police—charged with a felony count of Reckless Endangerment for streaming aerial footage of police violence toward demonstrators—Henke testified that Turgeon’s drone could have fallen from the sky, injuring people. According to cell phone footage, Henke falsely asserted to Turgeon that his actions were illegal, and attempted to seize the drone. Henke later admitted his accusations were wrong.

Turgeon was found not guilty on all counts, but not after police described his reporting as “an act of violence.”

“North Dakota once again exaggerated and lied to push their agenda,” Rhianna Lakin, a prominent member of the commercial drone community who provided on-the-ground support and training for Indigenous pilots told us. “The FAA acted off hearsay only with no factual proof to back up the claims. This is a scary reaction.”

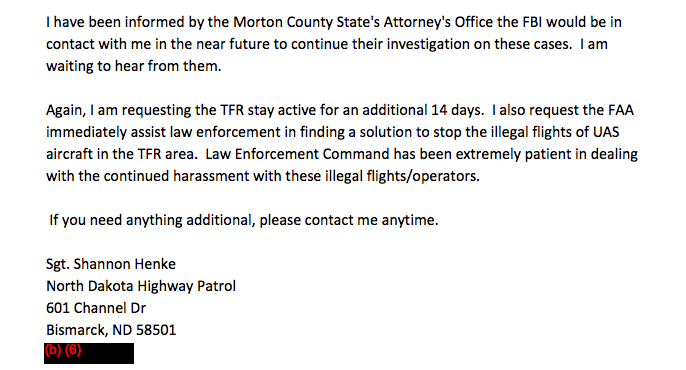

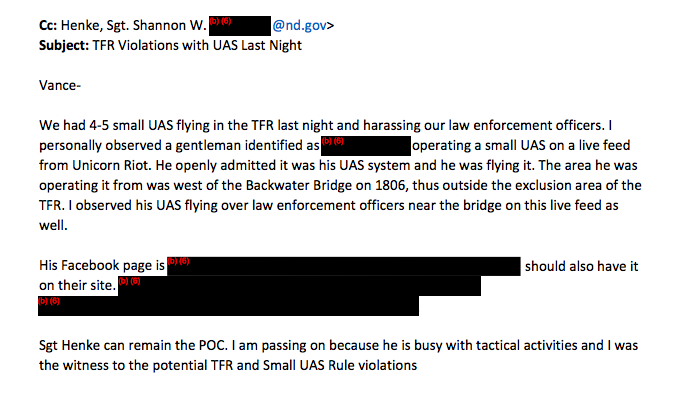

Emails also revealed that Henke planned to speak with the FBI regarding its investigation of Dean Dedman Jr., a Standing Rock Hunkpapa citizen who was registered with the FAA, over allegations that he piloted his drone too close to police helicopters during a TFR. Dedman claimed his activities were constitutionally protected.

“Due to the violence that has in fact been displayed over and over again throughout this period of civil disorder and riots, it is only a matter of time until a law enforcement officer, a lawful protester, or member of the public is injured (or worse yet killed) as a result of unlawful actor usage of UAS,” Sean Johnson, Chief Planner at North Dakota DES wrote to FAA Special Operations Security managers in November.

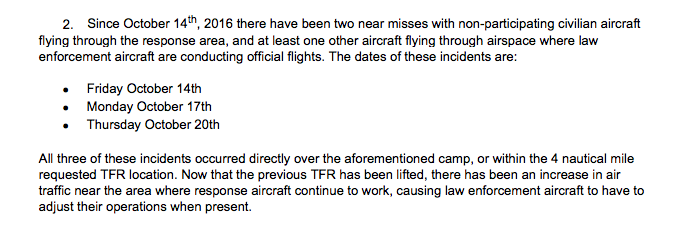

Johnson cited several “near misses” between civilian and law enforcement drones. He also described “undocumented” cases of demonstrators using “high powered laser pointers and spotlights” to blind Morton County pilots.

There have been no documented instances of demonstrators grounding police drones with either ammunition or lasers. However, in October, the Morton County Sheriff’s Office was filmed shooting down Dedman’s drone at the Standing Rock site. The FAA issued a comment saying it was investigating the incident.

At the time, independent drone attorney Peter Sachs wrote a blog post noting that the FAA’s TFR may have been aimed at suppressing free speech and drone journalism, and that all the news reports suggested Indigenous drone pilots were flying peacefully:

“Aside from being a federal felony, shooting drones (which are “aircraft”), from the sky most certainly presents a hazard to persons or property on the surface because of a universally-recognized law—gravity. However, that particular hazard, created solely by law enforcement, could be easily eliminated if they simply stopped shooting down drones. Law enforcement at Standing Rock is also flying aircraft, (displaying altered registration numbers in violation of federal criminal law), at extremely low and unsafe altitudes over those protesting against the pipeline, arguably in violation of FAR 91.13 , which prohibits careless and reckless flight.

That being the case, perhaps law enforcement aircraft, and only law enforcement aircraft, should be barred from flight over Standing Rock.”

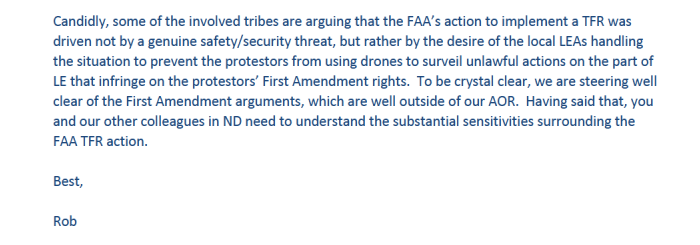

In an email to Johnson, Robert Sweet of the FAA’s Strategic Operations Group noted his agency was “steering well clear of the First Amendment arguments, which are well outside of our AOR [area of responsibility]. Having said that, you and our other colleagues in [North Dakota] need to understand the substantial sensitivities surrounding the FAA TFR action.”

It’s unclear what Sweet meant when he said First Amendment issues were outside the purview of his agency, a Homeland Security Division. Law enforcement have repeatedly questioned the intention of press at protest sites, even detaining journalists after mass arrests at DAPL sites, and transcripts about a TFR at the Ferguson protests in 2014 note specifically that the FAA implemented the TFR to prevent journalists from reporting.

The FAA seemingly understood how complicated the matter was; Brian Throop, another FAA official, told Johnson, “There is a very robust discussion here about whether or not to issue the TFR. Management at the highest levels of the FAA is aware of this and is involved in the discussion.”

FAA officials questioned whether Johnson’s undocumented complaints of near-misses warranted action. “…simply citing an incident or two poses problems,” the FAA told him.

In an email to Motherboard, Les Dorr, a spokesperson for the FAA said it “carefully considers requests from law enforcement and other entities before establishing TFR in U.S. airspace.”

“The TFR over the pipeline protest was approved to ensure the safety of aircraft in support of law enforcement and the safety of people on the ground,” Dorr said. “The TFR included provisions for media to operate aircraft—both traditional and unmanned—inside the TFR, provided that operators complied with the language of the Notice to Airmen. In the case of unmanned aircraft, operators also had to comply with the requirements of Part 107 and coordinate beforehand with the FAA. We did not deny any requests from media who met those requirements.”

It is true that the FAA did eventually approve a journalist to fly a drone above Standing Rock, but this effectively creates the situation of the Federal Government giving out permits to practice journalism. Part 107 of the FAA’s drone regulations is a licensing process for commercial drone operators that can’t be obtained in a matter of minutes (taking the knowledge test to get a remote pilot’s license costs $150); many of the Indigenous journalists weren’t monetizing their work. Meanwhile, Part 107 has some restrictions against night flying; much of the footage of police brutality involving water cannons and tear gas was captured at night. In many cases, the time and location of newsworthy moments aren’t broadcast in advance and a TFR has the effect of limiting the practice of journalism.

In this case, the FAA appears to have at least considered that the TFR would restrict the ability of journalists to collect information, and previous incidents between drones and first responders above wildfires have shown that the FAA has a tough job here. The FAA must weigh the First Amendment against the safety of those in the air and those on the ground, but in order for it to do a fair job, it needs to be fed accurate information. In Standing Rock, Indigenous demonstrators had no chance to plead their case and the concerns of law enforcement were accepted by the FAA at face value.

“We went to document Dakota Access over broken treaty lands, and not police. But police became a distraction and became violators of the Constitution. There was nobody holding them accountable until we went live,” Myron Dewey, a professional filmmaker and drone pilot, told us.

Dewey, whose film company Digital Smoke Signals released a documentary about Standing Rock this year, said he recorded “human rights violations” being committed by law enforcement. He saw civilian drones being shot down by police with bean bags, plastic bullets, and BB pellets, and said his personal drone was stolen by law enforcement.

“What you guys saw at Standing Rock is what we see all over the reservation,” Dewey said.

What remains clear is that basic acts of journalism, even outside exclusion zones, were interpreted as harassment by police. For instance, Johnson reported a Unicorn Riot journalist to the FAA for live-streaming via drone in an area not covered by the TFR, linking to his Facebook page, and other information that FAA chose to redact.

The North Dakota Department of Emergency Services did not respond to a Motherboard request for comment. Law enforcement in North Dakota refused to respond to a Motherboard request for comment.