Researchers Link CCleaner Hack to Cyberespionage Group

Credit to Author: Lucian Constantin| Date: Thu, 21 Sep 2017 11:53:54 +0000

The recent attack that resulted in 2.2 million users installing infected versions of a popular Windows system optimization tool might have been the work of a sophisticated cyberespionage group with a history of software supply chain compromises.

Researchers from two security companies have established links between the malicious code surreptitiously added to the program’s installer and malware previously used by a prolific group of Chinese hackers that once broke into Google’s corporate infrastructure.

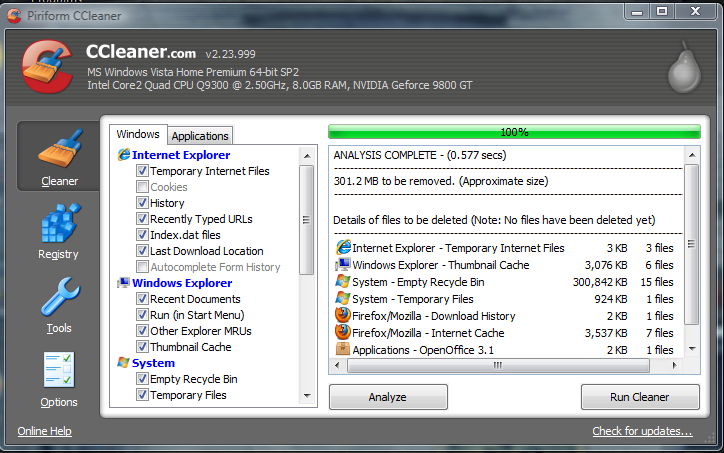

On Monday, it was revealed that the official and digitally signed installers for two versions of CCleaner—a utility for removing temporary files and invalid registry entries on Windows computers—contained a backdoor program capable of installing additional malware. These malware-laden programs were distributed between August 15 and September 12.

The fact that the malicious code was added to CCleaner before it was compiled suggests that hackers gained access to the development infrastructure of Piriform, the company that makes the tool. Piriform was acquired in July by antivirus maker Avast.

As far as the malicious code found in CCleaner is concerned, there is overlap with APT17/Aurora, Costin Raiu, director of the Global Research and Analysis Team at antivirus vendor Kaspersky Lab, who analyzed the malware, told me.

APT17, also known as DeputyDog, is a cyberespionage group that has been operating for over a decade. Over the years, the group has hacked into government entities, non-government organizations, law firms and companies from various industries, including defense, information technology and mining. The group was also behind Operation Aurora, a high-profile attack in 2009 that affected Google and over 30 other companies.

The backdoor included in the 32-bit versions of CCleaner v5.33.6162 and CCleaner Cloud v1.07.3191 was designed to gather identifying information about the infected computers and send it to a hard-coded IP address. If the server was unreachable, the malware would generate random-looking domain names based on a special algorithm and attempt to contact those.

Attackers often use a lightweight malware program for the first stage of an infection in order to perform reconnaissance and gather information from the infected systems in order to identify potentially interesting targets for which they will then deliver more specialized malware. Information such as process lists can help identify which security products are running and must be evaded while computer and domain names can reveal the organizations the affected systems belong to.

The backdoor program included with CCleaner also attempted to download and execute additional malware from the command-and-control server. Cisco Systems’ Talos group confirmed in a new report Wednesday that at least 20 victim machines belonging to high-profile technology companies were served such secondary payloads.

Jay Rosenberg, a researcher with security firm Intezer also confirmed that the CCleaner backdoor has code that’s identical to that used in APT17’s past malware tools. Intezer’s technology is specifically designed to find code similarities in malware.

“The code in question is a unique implementation of base64 [encoding] only previously seen in APT17 and not in any public repository, which makes a strong case about attribution to the same threat actor,” Rosenberg wrote in a blog post.

Raiu also pointed out that while the code overlaps with APT17, the command-and-control infrastructure used matches that of a newer attack group. However, there is a connection between these the two groups, as they’re both tied to a larger cyberespionage organization known in the security industry as Axiom.

Axiom was documented in 2015 by threat analytics firm Novetta in partnership with other security vendors. It is a sort of umbrella group responsible for many cyberespionage campaigns over many years and which Novetta believes are coordinated by China’s intelligence apparatus.

“FireEye found infrastructure overlap with a nation state threat actor,” Christopher Glyer, the chief security architect at security firm FireEye, said in a public discussion on Twitter about the CCleaner incident. “CCleaner is used in lots of orgs (even if primarily consumer focused). Supply chain compromise is a perfect vector for a nation state to use,” he said in another message.

FireEye did not immediately respond to a request for more information, but Glyer raises a good point: If this was a cyberespionage operation—and evidence found so far suggests it was—then the primary targets were likely CCleaner’s business users.

It’s worth pointing out that CCleaner Cloud, which was affected, is a business product. Piriform says on its website that the program is trusted by organizations such as Airbus, Siemens, Intel, Oracle, Samsung, DHL, Staples, Princeton University and the City of Vancouver.

And there’s evidence that companies have indeed been affected. Endpoint security vendor Morphisec, one of the two security companies that independently identified the backdoor and reported it to Avast, detected it at “customer sites” and its customers are businesses.

Many enterprises use CCleaner, especially manufacturers and service providers, Michael Gorelik, Morphisec’s vice president of research and development, told me. Morphisec’s technology detected attempts to install the backdoor on around 200 systems at four different clients, but the company only receives attack logs from customers who agreed to share such data, he said.

The Cisco Talos researchers managed to obtain files from the backdoor’s command-and-control server and they show that attackers attempted to use the backdoor to deploy specialized malware to a number of companies including HTC, Samsung, Sintel, Sony, Intel, Vodafone, Microsoft, VMware, O2, Epson, Akamai, D-Link, Gmail (Google) and Cisco itself.

“These new findings raise our level of concern about these events, as elements of our research point towards a possible unknown, sophisticated actor,” the Cisco researchers said. “These findings also support and reinforce our previous recommendation that those impacted by this supply chain attack should not simply remove the affected version of CCleaner or update to the latest version, but should restore from backups or reimage systems to ensure that they completely remove not only the backdoored version of CCleaner but also any other malware that may be resident on the system.”

The Talos researchers also reviewed Kaspersky’s claims that there is code overlap with Axiom and confirmed the findings. This is by no means proof of attribution, but is important information to be considered, they said.

Gorelik is skeptical about attempts to attribute this attack to a particular hacker group based on code similarities. He argues that the backdoor’s code footprint is too small to draw definitive conclusions and that the memory injection technique used by the malware is increasingly common among attackers. However, he agrees that breaking into Piriform’s infrastructure in the first place and adding the malicious code without being detected required a significant effort and knowledge of how software development systems work.

The attackers were well-trained, he said. “They knew exactly who to target and what to do.”

Gorelik is convinced that supply-chain attacks will increase in frequency, but believes that there are already other products out there with malicious code added to them that have yet to be discovered.

The Axiom attackers have a history of launching supply-chain attacks. Researchers believe they are responsible for Kingslayer, an attack reported in February by RSA which involved malware being embedded in a system administration tool. According to Raiu, the ShadowPad attack reported by Kaspersky Lab last month, where hackers managed to inject malware in an enterprise server management tool, is linked to Winnti, another group associated with Axiom.

“A rise in supply chain attacks is something we feared for some time and now it’s like a nightmare coming true,” Raiu said. “Both recent cases, ShadowPad and CCleaner are similar in implementation and have certain links to the Axiom APT group, described in detail by Novetta in 2015. One of the most important questions is: are these the only attacks of this kind out there, or how many others are not discovered yet?”

Avast initially said that it doesn’t believe a second-stage payload was ever delivered to affected users, of which around 730,000 still have the affected version of CCleaner installed on their computers. But after Cisco Talos’ revelations Wednesday, the company backtracked and published a new blog post confirming that the attack was an APT (Advanced Persistent Threat) with the goal of targeting select users.

“Specifically, the server logs indicated 20 machines in a total of 8 organizations to which the 2nd stage payload was sent, but given that the logs were only collected for little over three days, the actual number of computers that received the 2nd stage payload was likely at least in the order of hundreds,” the company said.

The second-stage playload injects its code into two DLL files of legitimate products from Corel and Symantec. It also establishes persistence on the system by storing malicious code in the Windows registry and searches a GitHub and a WordPress account for additional payloads.

“All of these techniques demonstrate the attacker’s high level of sophistication,” Avast said.