Florida’s Ayahuasca Church Wants to Go Legal

Credit to Author: Josh Adler| Date: Wed, 20 Sep 2017 15:00:00 +0000

When the government contacted Soul Quest church in Orlando in August of last year, founder Chris Young had already administered illegal hallucinogens to thousands of his congregation members without federal approval.

In the letter, the US Drug Enforcement Agency asked Young and his cohort to apply for exemption status, which would allow them to provide ayahuasca, a hallucinogenic Amazonian tea, legally. It would also make Soul Quest the first homegrown psychedelic healing center in the US, permanently altering the way the government views the intersection of drugs and faith.

The DEA’s letter was unprecedented—the agency has never solicited an organization to apply for an exemption, although several others have attempted petitions. And the exemption process is an open-ended timeline, entirely dependent on the DEA’s opaque policy bureau. (Other cases have taken up to three years.)

In a bold move, Soul Quest continued its retreats for over a year after receiving the DEA’s entreaty. If their application is denied, the church could be shut down. At worst, Young, and possibly others, could face prosecution for distributing what are classified as Schedule I substances. He isn’t scared: “Every time the DEA has messed with a church, they’ve lost and lost big,” he told me.

While Young’s church could benefit from the legal validation of exemption status, experts within the psychedelic community are skeptical. They say the agency might be trying to strongarm the church to keep it close, and maybe even shut it down. (I contacted the DEA multiple times but they did not respond to requests for comment.) And though Young’s congregation of 3,000 people feel they share a faith, there is also the looming question of whether their worship can sustain its own syncretic methods, or is guilty of mass cultural appropriation.

In August of this year, I paid Florida’s ayahuasca church a visit.

*

Soul Quest makes for a contrasting presence amid Orlando’s carpools of Disney-going mice and duck worshippers.

The property is modest, with a simple sign of refuge placed above its doors. Across that threshold, there are both hugs and paperwork. There are also bunk beds to sleep on, and about 20 church members arriving from all over the country.

When I arrived at a weekend retreat this summer, I met Robin from Dallas who’s down with animal spirits and hypnosis, her grandson Kyle, and their friend Radhika, a nurse turned kindergarten teacher. There were also members of Veterans for Entheogenic Therapy (VET), a group led by former Marine Ryan LeCompte, which provides funding and year-long integration therapy for veterans to do ayahuasca ceremonies in Peru, and now Soul Quest. There was a volunteer named Alan who announced: “We use Florida water for cleansing.”

The conversations ranged from acknowledging living and lost fathers, to letting go of mothers and addictions, to forgiving mad uncles, false politicians, and husbands.

With the support of these members, Young, who is 43, is hoping federal officials will give Soul Quest the green light to legally administer hallucinogenic substances within a “sincere” religious context. But the laws, and the rights of the congregation, are complicated by outdated policy that don’t account for psychedelics’ medical benefits or ancient spiritual traditions.

Other groups that have petitioned for exemption have come up short in their claims of holding a “sincere” belief system, which would allow federal authorities to overrule their practices. The Church of Reality in California tried to put cannabis on the holy altar, but could only say, “It leads to cool ideas.” Other ayahuasca groups have also failed to provide more than flimsy Indigenous appropriations with strong entrepreneurial undercurrents.

Today Soul Quest claims no official lineage. Ayahuasca is considered the group’s central sacrament, along with rapé, a tobacco, and kambo, a pain remedy derived from frogs in the rainforest. The congregation has adopted the Ayahauasca Manifesto, which appeared anonymously online two years before Soul Quest was formed, as its central text.

The First Amendment’s Free Exercise clause protects citizens’ rights to practice their religions as they please, unless protections are deemed necessary by a court. Religious spaces in the US are therefore expressly not to be coerced by law or government interference (i.e., promoted or inhibited).

Young’s argument for his church’s ongoing use of ayahuasca stems from updates to the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA) made in 2009. The current guidelines for gaining exemption state that once a group meets the “minimal” standards to establish themselves as a religion, the government can’t burden citizens’ right to exercise their religious beliefs without compelling evidence that some greater interest must be upheld. The exemption process allows the DEA a completely open-ended timeline to review petitions. However, Soul Quest’s legal team has submitted a request for a decision by the end of this year.

On paper, Soul Quest’s 157-page application details a congregation that blends traditions. Their claim includes over two years of ceremonial practices, an engaged membership, and the manifesto as liturgy. Soul Quest devotees read the text aloud during every integration session, like a Dharma talk, sermon, or Torah portion; a practice with enough impact to prompt some members to joke about the group being a cult.

And Soul Quest’s Ayahuasca Manifesto certainly goes further than the anecdotal writings of Ayahuasca Healings, a group led by Christopher “Trinity” de Guzman, whose application exemption in 2016 was shot down amid plenty of media attention. At Soul Quest, ayahuasca is defined as a “teacher prophet” with revelations resulting from a “sacred mixture.”

But Bia Labate, a veteran Brazilian anthropologist who has extensively researched ayahuasca, has her reservations. “What’s being judged is not whether Soul Quest does serious work, but whether it is a true religion, and whether ayahuasca is so central to the exercise of this religion that it trumps drug laws,” she told me.

“Everything is fun, sexy, and cool until you have a real problem. No one in 2017 can claim naïveté on ayahuasca. Why does he need to go online or advertise? Ceremonies end up looking like a business.”

*

At Soul Quest, facilitators come from various backgrounds. There was a tobacco cessation specialist, and a yoga teacher. They constantly circulated to check in with members milling about the many common spaces: living room, kitchen, studios, porch, lawn, pond, and nature trails. The church’s vibe is not unlike other sanctuary spaces I’ve visited—from temples and churches to mosques.

Except for the stacks of empty white buckets. Along with the mindblowing hallucinations, drinking ayahuasca usually includes the formidable caveat of bodily excretions like vomit and bowel movements. The release is considered cleansing and fondly referred to by many as “purging.”

“Integration of the experience is different for everyone,” Nischalã, a staff facilitator, told the group. She was referring to integration sessions: facilitated group discussions, also common in psychotherapy practices with psychedelics, that are a crucial part of helping people understand how experiences from their trip can transform and heal.

In the den after one long night ceremony, Chris Young, outspoken and tireless, poetically encouraged those gathered to share their visions: “Don’t overlook any details during reflection. Even the leaf that is dead has meaning. It’s supporting life.”

Founding a church of psychedelics was never something Young saw himself doing. In his previous life, he was an EMT, where he tells me he observed pharmaceutical companies manipulating doctors to prescribe powerful drugs like oxycontin, one of the lethal forces behind the country’s opioid epidemic. Young says he visited many crime scenes, and helped many overdose victims. Eventually he was burnt out, and he and his wife went to Germany for about a year. After the break, he wanted to get back into medicine, but not the Western kind.

“My god is planet Earth. My Jesus, my savior, is ayahuasca.”

Then “Mother Ayahuasca” found him during a trip to Spain. Young gave himself what he calls a surprise birthday present of an 11-day retreat. On the third day he learned his five-months-pregnant wife had a miscarriage. He says his ayahuasca-powered visions revealed “shadow people” that told him that they would have another child and he should keep going with the ceremony. The same visions also instructed him to go back to the US and open a church, “to provide the medicine [ayahuasca] to future generations, make it accessible, and propagate its growth.”

Soon after opening Soul Quest in 2014, Young’s wife, Verena, became pregnant, eventually giving birth to a healthy boy. To him, this was a prophesied sign. “My god is planet Earth. My Jesus, my savior, is ayahuasca.”

The concern of cultural appropriation looms over Soul Quest. Ayahuasca is an earthy infusion traditionally brewed from the caapi vine and chacruna tree bark native to the Amazon. It has been offered as a sacrament in rural Brazil and Peru for thousands of years. When consumed, the tea’s active psychedelic compound, DMT, sparks up to six hours of visions by activating serotonin receptors in the brain. These visions can include complex geometrical patterns, spiritual insights, and intensely personal Jungian archetypal scenarios, meant to be interpreted with a guide, or shaman.

Without that context, its use could be rendered recreational. And weak claims to Indigenous lineages are a big problem, according to Labate, perhaps the most published author on current social issues relating to Indigenous psychedelics. “Several experts advised Chris Young not to file this petition. He doesn’t seem legally prepared. For one thing it’s a serious problem to claim to be a Native American church,” she told me.

Young explained that he was initially encouraged by the Oklevueha Native American Church (ONAC) to seek affiliation with them. But when he discovered they couldn’t legally protect him, he decided that establishing a new faith would be more beneficial.

And it’s not just religious freedom he is seeking. According to the petition Soul Quest filed with the DEA the week before I visited, which Motherboard has obtained, a core part of the church’s mission is to provide members access to the ‘cognitive freedom’ these ayahuasca experiences provide, and to protect the congregants’ freedom of self-determination (i.e., the right to control their own mental processes), including psychedelic-induced spiritual visions. If members join the church to access and exercise those freedoms, then the DEA must provide just cause that governmental interference is necessary.

This precedent has been applied to psychedelic cases before, but only to those with roots in Indigenous communities. A 2006 ruling by the US Supreme Court protected the União do Vegetal church’s use of ayahuasca in New Mexico. Another syncretic church with Brazilian roots, the Santo Daime, also soundly proved their right to use ayahuasca in ceremonies in court in 2011.

It will help Young that the science and support for ayahuasca in mainstream America has gotten stronger in the last six years. The Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPs) and other leading advocacy groups like the Drug Policy Alliance (DPA) and Ayahuasca Defence Fund continue to announce encouraging results from studies suggesting the medical potential of ayahuasca and other therapy-assisted psychedelics. If administered correctly, there is evidence they could help treat depression, PTSD, addiction, and other trauma-related conditions.

“Ibogaine [a West African psychedelic root] and ayahuasca have tremendous potential and MDMA does too,” says Rick Doblin, head of MAPS. “Veterans who do harm reduction therapy with these substances realize that they’re using opiates as an escape with high success rates.”

Meanwhile, the latest case histories coming out of doctor Joseph Tafur’s clinic in Peru have been deemed “triumphant” by renowned colleague Gabor Maté. Along with treating mental health disorders, they include relief from chronic conditions such as psoriasis, migraines, and inflammatory bowel disease mainstream medicine relegates to symptom management.

But even as the benefits of psychedelics are becoming more apparent, Jag Davies, communications director of the DPA, wrote earlier this year, “Public support for legal access to psychedelics remains low due to unsubstantiated myths that are vestiges of the drug war.”

*

If Soul Quest receives the government go-ahead, it would set a new precedent in the tolerance of psychedelics, not just ayahuasca. Furthermore, it could open the door for other psychedelics churches to go mainstream: Their proliferation could usher in the largest spiritual revival in our country since The Great Awakening.

Psychologist Neal Goldsmith, a founder of the Horizons psychedelics conference in NYC, and one of the leading advocates for legalization, tells me large-scale religious reintroduction of psychedelics could also shift the trajectory of our cultural values. His vision goes beyond exemption status.

“Over time the emerging divinity schools will train students to use active chemicals for scientific human development and maturation, as well as end-of-life care,” he said in an interview. “Substances are providing a clearer view on reality.”

Read More: When the Drugs Hit

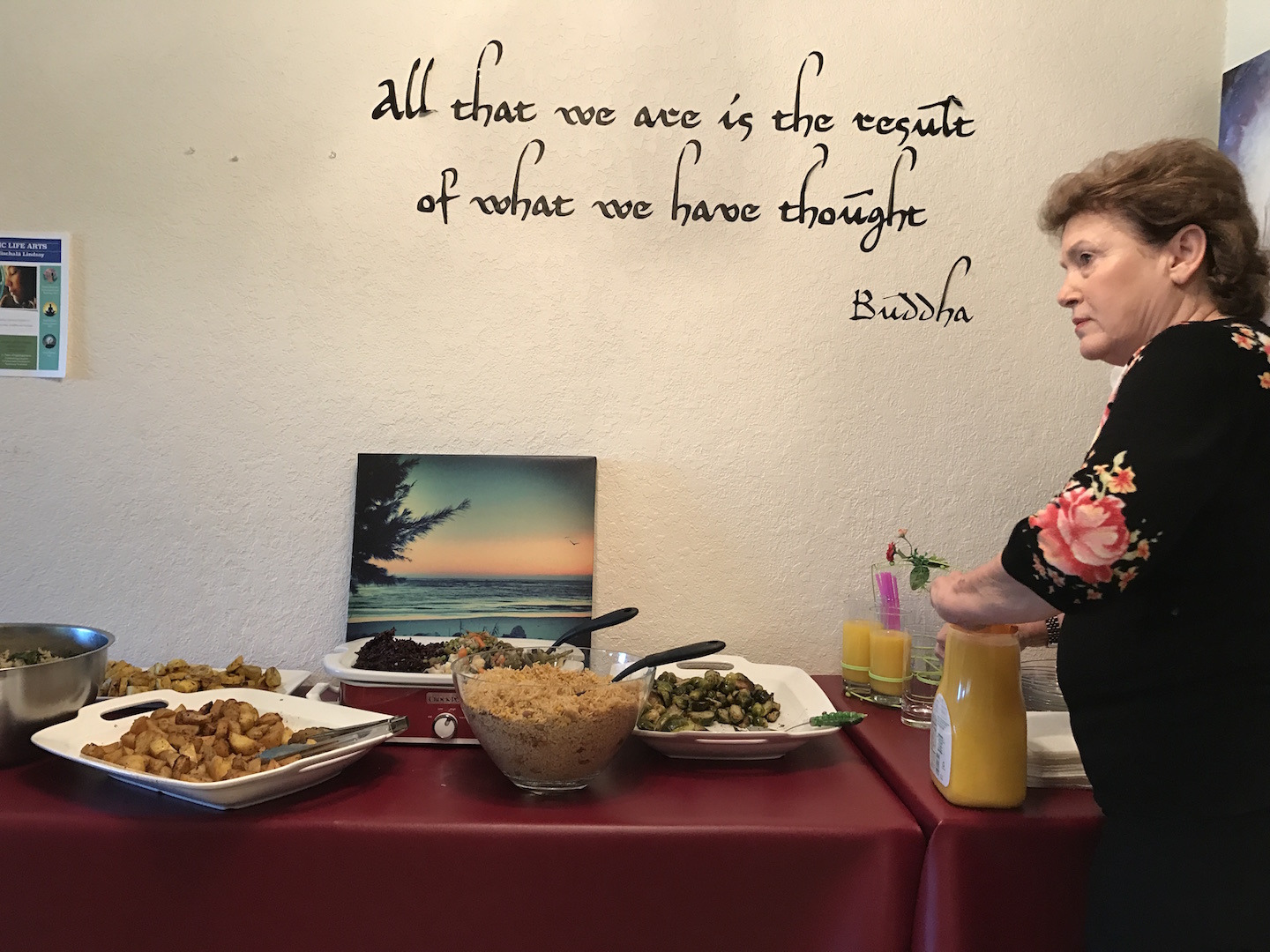

The sense of clarity is what many of Young’s members are hoping for at the Orlando church. On an August evening, members laid on cushions on the ground wincing through the sting and swell of kambo treatments, while others relaxed nearby enjoying Lipton iced tea and deviled eggs served by Bonnie, a 68-year-old volunteer.

Bonnie loves feeding people. She showed up at the church a year-and-a-half ago, and no one can deny her fruit salad or seasoned roast potatoes, so she keeps bringing dishes. As a “secret flower child,” Bonnie told me she’s slowly inching herself toward trying ayahuasca, but she’s still squeamish about telling her conservative friends where she goes on weekends.

Besides Bonnie and the staff, there were many other volunteer caretakers on hand, like Alan with the Florida water, who devotedly sets up buckets and lawn beds for ceremonies. Alan said that other places don’t take enough care with people, and wants visitors at Soul Quest to have the best experience possible. He himself used to suffer intense headaches for years before drinking ayahuasca regularly. Now, he said, the headaches only happen once every few months instead of daily.

In the living room, integration continued, as an Orlando businessman spoke about his visions during an optional 100-degree day ceremony. “The trees looked like they were hugging us. The ground is alive. Ayahuasca doesn’t necessarily give you what you want.”

A local couple, feeling closer to each other after the weekend of tripping balls, appreciated that the church exists to support their “rights” to enjoy “a long weekend confronting their blocks and struggles.” That’s what they came for, and that’s what Soul Quest delivered: ayahuasca, playlists, yurts, Bonnie’s deviled eggs, storms, prayer, songs, awe, and all.

Get six of our favorite Motherboard stories every day by signing up for our newsletter.