Hoarders Are Confronting Clutter in Virtual Reality

Credit to Author: Jacob Dubé| Date: Mon, 11 Sep 2017 16:27:18 +0000

How would you feel standing in a cramped room surrounded by garbage, newspapers, and random camping equipment? Turns out, even when this mess is simulated in virtual reality, it’s pretty stressful. I know this because I recently participated in a VR study of hoarders, who are using the technology to confront their disorders.

Researchers out of Ryerson University in Toronto are conducting a study to test the different factors that relate to hoarding, putting test subjects through a series of virtual reality experiments in which they confront hoards of stuff while the researchers measure their stress response. They’re finding that even self-identified hoarders don’t like being around too much clutter.

Hoarding, which is estimated to affect 1 in 50 people, is still poorly understood. It is considered a facet of obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), Hanna McCabe-Bennett, the lead researcher who’s doing the study as part of her dissertation in chemical psychology, told me. She said that experts are starting to wonder if it’s its own, separate condition. According to the International OCD Foundation, people with a hoarding disorder collect items to the point where it causes them personal distress. Having that much stuff in your house, especially if it’s garbage or old food, can pose serious health risks, and block air vents or exits in the event of an emergency.

There aren’t many existing treatments right now other than psychotherapy, where the hoarder discusses the root and challenges of their disorder. And there’s still a lot of stigma attached to it, which prevents people from seeking help.

“They shame you. They embarrass you. They make you feel like you’re a bad person. And that’s not going to get anybody any healthier,” Roxanne Tellier, one of the participants in the study whose collection includes thousands of books and clothes, told me in an interview.

McCabe-Bennett is looking at three aspects related to hoarding—information processing, emotional experiences, and how comfortable a person is when faced with different amounts of mess, or whether they prefer their own stuff to a stranger’s.

“People that live in cluttered environments are actually suffering a lot more than we realize”

To research those factors, test subjects—some of whom identified as having a hoarding disorder, and others who did not—do a written memory test, then go through three different VR situations, lasting about five minutes each, while McCabe-Bennett and her team analyse their reactions and stress levels through heart rate and sweat monitors.

When I tried out the simulations, the first brought me into a regular-looking living room. Every 20 seconds or so, the room would fill up with more stuff—everything from old clothes to newspapers to camping supplies, like tents and sleeping bags. Once I saw an entire canoe pop up behind me, I was starting to feel claustrophobic.

According to McCabe-Bennett, that first simulation is intended to test the comfort levels of the subjects when they’re confronted with a mess, and though her results aren’t finalized, she said that she was surprised to find that people with a hoarding disorder didn’t actually feel more at ease as random stuff piled up. In fact, they showed increasing levels of distress.

“People that live in cluttered environments are actually suffering a lot more than we realize,” McCabe-Bennett said.

After being shown a series of videos intended to induce negative or neutral emotions, subjects were then taken to a VR simulation of a packed store—McCabe-Bennett and her team took 360-degree photographs of the Toronto vintage store Ransack The Universe—to see if those emotions would induce a desire to buy more things than someone without a diagnosed hoarding disorder typically would.

Read More: My Friend, the Compulsive Hoarder

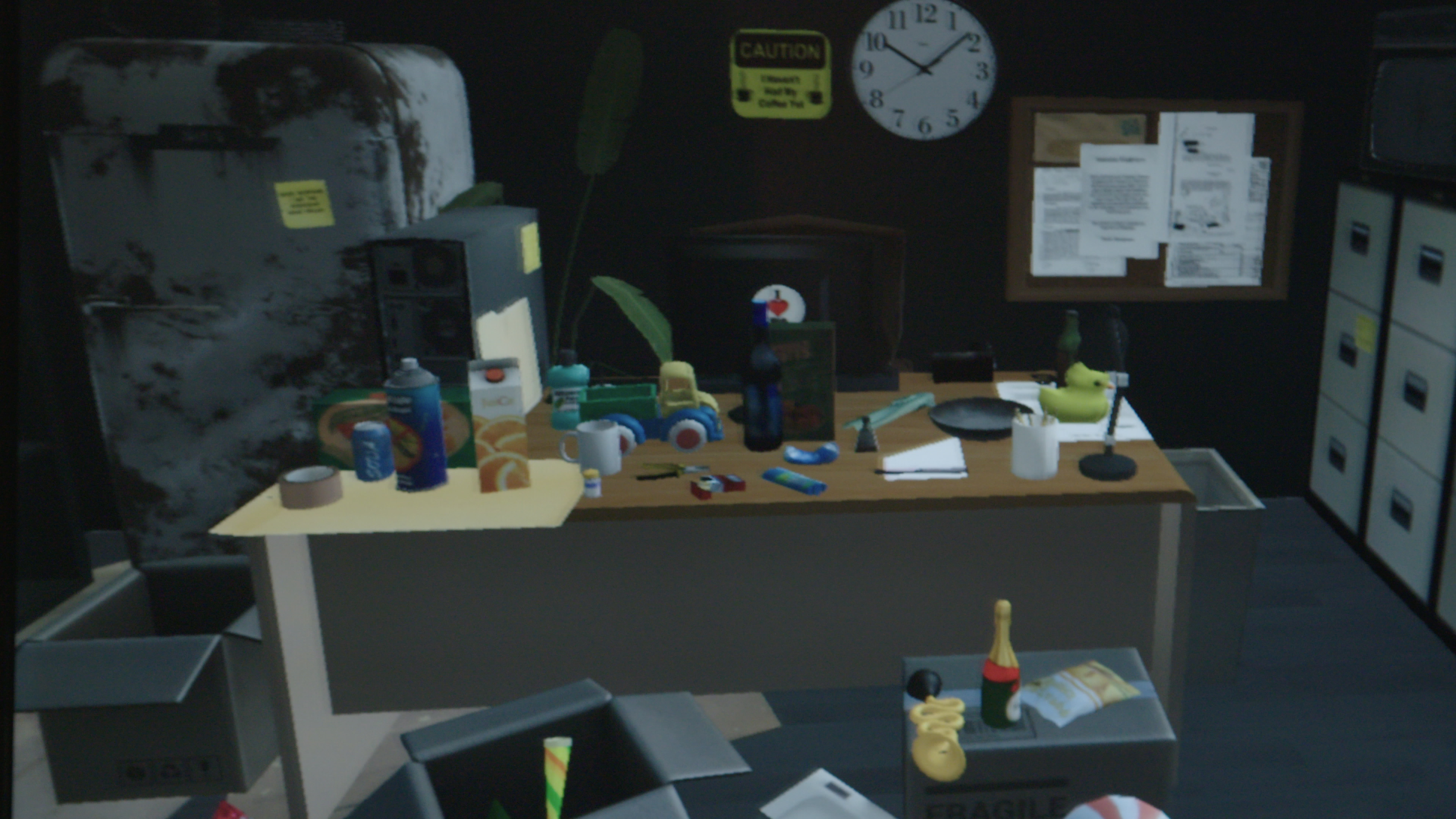

Those two VR tests were made using 360-degree images, but the last one was made from scratch in the Unity engine, a popular tool for making 3D video games. Though it was less realistic than the photos, it was convincing enough. I was dropped in a cluttered home office, filled with children’s toys and other junk. As I moved around in the room, slowly realizing I get motion sick very easily, I kept finding more and more stuff—the clutter never ended.

That simulation is intended to test the memory and organizational skills of the subjects, as they remember where certain objects are located and later are asked to talk about how they would organize or tidy them up. According to McCabe-Bennett, hoarders often keep objects because they’re associated with specific memories they’re afraid to lose.

“They might think that if they discard an object, they will also lose the memory [of what the treasured object represents],” McCabe-Bennett said. “So they think that they need to have the object as a trigger for nice memories that they have.”

Tellier told me that her problem with hoarding—or collecting, as she prefers to call it—stemmed from her childhood. When her parents separated when she was young, she, along with her mother and sister, had to pack up and make the trip from Alberta to Montreal. But she could only bring one suitcase, and everything else had to be left behind.

Tellier now has a collection of over 10,000 books in her home, as well as a huge clothing collection, which she never thought was an issue. But her husband disagrees. Tellier has a sense of humour about her collecting, saying, “I’m somewhere in the middle of people that collect elastic bands and people that save their bottles of urine.” She agreed to participate in McCabe-Bennett’s study to get some more insight on her habit.

Tellier said that the added layer of looking through a VR headset can take away any personal attachment to clutter. She said it allows her to see things for what they really are.

“You’re standing back. There’s perspective,” she said.

Though McCabe-Bennett said her research is about understanding the disorder rather than treating it, she hopes the results will help develop treatments later on. One idea would be to expose a patient to a VR display of their own home and clutter to deal with it in a safe environment, like a therapist’s office.

“It’s something that’s difficult to overcome, but it’s possible,” McCabe-Bennett said. “It’s one of those things that takes a lot of support from family and professionals to get to the other side.”

Get six of our favorite Motherboard stories every day by signing up for our newsletter.