Rural America Is Building Its Own Internet Because No One Else Will

Credit to Author: Kaleigh Rogers| Date: Tue, 29 Aug 2017 15:00:00 +0000

Broadband Land is an ongoing Motherboard series about the digital divide in America. Follow along here.

Dane Shryock walked over to a map hanging on the wall of the county commissioners’ office in downtown Coshocton. He ran his finger along a highway to point out directions to a family farm, where he told me I’d find an antenna placed atop a tall blue silo.

“You’re going to want to go straight down 36, turn left on this county road,” Shryock, one of three county commissioners in Coshocton, Ohio, said. “There’s a cemetery on the left, and then you’ll see a big red barn.”

I snapped a photo of the map. The old-school directions were necessary because the address doesn’t exactly show up on Google Maps and, besides, my phone lost all signal after about the third hill on that county road. It was a blistering hot July day in Appalachian Ohio and I was on a mission to see firsthand how rural communities have stopped waiting for Big Telecom to bring high-speed internet to them and have started to build it themselves.

About 19 million Americans still don’t have access to broadband internet, which the Federal Communication Commission defines as offering a minimum of 25 megabits per second download speeds and 3mbps upload speeds. Those who do have broadband access often find it’s too expensive, unreliable, or has prohibitive data caps that make it unusable for modern needs.

In many cases, it’s not financially viable for big internet service providers like Comcast and CharterSpectrum to expand into these communities: They’re rural, not densely populated, and running fiber optic cable into rocky Appalachian soil isn’t cheap. Even with federal grants designed to make these expansions more affordable, there are hundreds of communities across the US that are essentially internet deserts.

But in true heartland, bootstrap fashion, these towns, hollows—small rural communities located in the valleys between Appalachia hills—and stretches of farmland have banded together to bring internet to their doors. They cobble together innovative and creative solutions to get around the financial, technological, and topological barriers to widespread internet. And it’s working, including on that farm down the county road in Coshocton.

It’s just one example of a story that’s unfolding across America’s countryside. Here, a look at three rural counties, in three different states, demonstrates how country folk are leading their communities into the digital age the best way they know how: ingenuity, tenacity, and good old-fashioned hard work.

THE ‘SILICON HOLLOW’

Letcher County, Kentucky

Letcher County is in the heart of coal country. The 300-square-mile, 25,000-person corner of Kentucky is tucked just across the border from Virginia. It’s rippled with endless rolling hills, dense forest, little towns, and boarded-up mines. Like many similar communities, the county has been hard hit by the waning coal industry.

But while politicians, including President Donald Trump, rally around the promise to “bring coal back,” the residents in many of these communities would rather look to the future. And in their mind, that future depends on high-speed internet.

“We view it as the next economic revolution for coal towns,” said Harry Collins, the chairman of the Letcher County Broadband Board, which formed late last year. “The majority of our railroad tracks are ripped up now—that revolution has played out. We feel that this [digital] revolution is just as game changing and life changing as those railroad tracks were in the 20s and 30s.”

I met Collins, and his vice chair Roland Brown, at a rural broadband summit in Appalachian Ohio, where the two men chatted strategy and ideas with other rural community leaders who were further along in the process.

Their region of Kentucky has the highest unemployment rate in the state, at 10.2 percent, according to the Kentucky Center for Education and Workforce Statistics. That’s more than double the national average. The population also has poor health indicators, a low education attainment, and may not be able to work outside the home because they’re caring for small children or aging relatives. Brown told me high-speed internet could help alleviate all of these pressures.

“If I’ve got reliable broadband, we can do telemedicine and bring in doctors from other areas,” Brown said. “If I can get people at home going to school online, I can raise up my education attainment level, which is only going to help me attracting employers in the long run. There are so many economic and social benefits of this.”

Other parts of Kentucky have already set a high standard for rural internet. Jackson County, in the middle of the state, is home to just over 13,000 residents spread across 350 square miles. It’s also home to gigabit internet available via fiber optic cable to every home in the county.

Eager to keep pace, Letcher established a voluntary broadband board, which had its first meeting in February this year. They began by surveying the entire region to pinpoint the areas with the least amount of access and quickly identified a stretch in the southwest corner of the county that was completely unserved. Ten businesses and 489 households covering 55 miles of mountain terrain had no access to high-speed internet whatsoever. The board decided to focus on this area first, which they’ve dubbed “Phase One.”

But it will be no easy task to connect this rural, rocky stretch of Appalachia. There are hills, hollows, and a lot of distance from the nearest hooked-up hub. The county has applied for a $1.3 million grant from the Department of Agriculture under its Community Connect program, and will find out in September whether that’s been approved. The County Fiscal Court has also committed $200,000 to the project, bringing the total to $1.5 million.

The plan, if the funding comes through, is to beam out a broadband signal from Whitesburg—the county seat ten miles away—to the Phase One area, then send fiber out to individual homes and businesses. But it will be a patchwork, with some fiber ending at the edge of a long hollow, and feeding into another tower that will transmit the signal to the folks living at the other end.

“We’re never going to be able to level the mountains off to get us connected to the rest of the world, but I can lay a piece of fiber that goes around that mountain.”

The board has established a “dig once” initiative, where any time roadwork or repairs are being done in the area, county workers are obliged to lay fiber at the same time. It’s also looking into innovative techniques for connecting along the highway, such as micro trenching, where the fiber optic cable is embedded a few inches into the road and blacktopped over.

“It cuts down your chances of animals taking your line down, or car wrecks that take it down, or storms that take it down,” Brown said.

The goal, over time, is to connect as much of the county as possible with a municipally-run broadband service that’s delivered like a utility—the same as electricity or water—and is self-sustaining, even if it’s not profitable. It’s all part of a larger effort in the state, led by Congressman Hal Rogers, who envisions tech as filling much of the gap left by the coal industry, and has proposed the dream of a “Silicon hollow.” As Letcher County prepares to lay its first miles of fiber, that dream is keeping these volunteers motivated.

“Broadband is the digital railroad but instead of extractive, we’re looking to it to bring jobs in, bring education in,” Collins said. “We’re never going to be able to level the mountains off to get us connected to the rest of the world, but I can lay a piece of fiber that goes around that mountain and then I can connect to the rest of the world.”

INTERNET ON THE TV

Garrett County, Maryland

Cheryl DeBerry likes to joke about her home county’s location in Maryland.

“We have Pennsylvania to the north, West Virginia to the east, west, and south,” DeBerry told me. “I’m not really sure where we’re connected to Maryland.”

Garrett County is located at the most western reach of Maryland’s panhandle. It sits just below the Mason-Dixon line, smack dab in the Appalachian Mountains. It’s rural, mountainous, and forested—pretty much the opposite of Cape Cod.

This geography was part of the reason why fewer than 60 percent of residents in Garrett County had broadband internet as of 2011, when county commissioners asked the economic development office, where DeBerry works, to identify its No. 1 priority for improving the region’s economy. DeBerry and her colleague quickly zeroed in on rural access to high-speed internet.

With a goal of 90 percent broadband coverage across the county, low population density, and plenty of hills and trees in the way, it wasn’t a simple proposal. To start, the county applied for a grant from the Appalachian Regional Commission—a federal-state partnership that supports economic development in Appalachia. With that money and some county funds, the local government hired a consultant to come up with a plan to reach its new goal: partner with a private company, and use any resources on hand to weave a network together.

Read more: The Town That Had Free Gigabit Internet

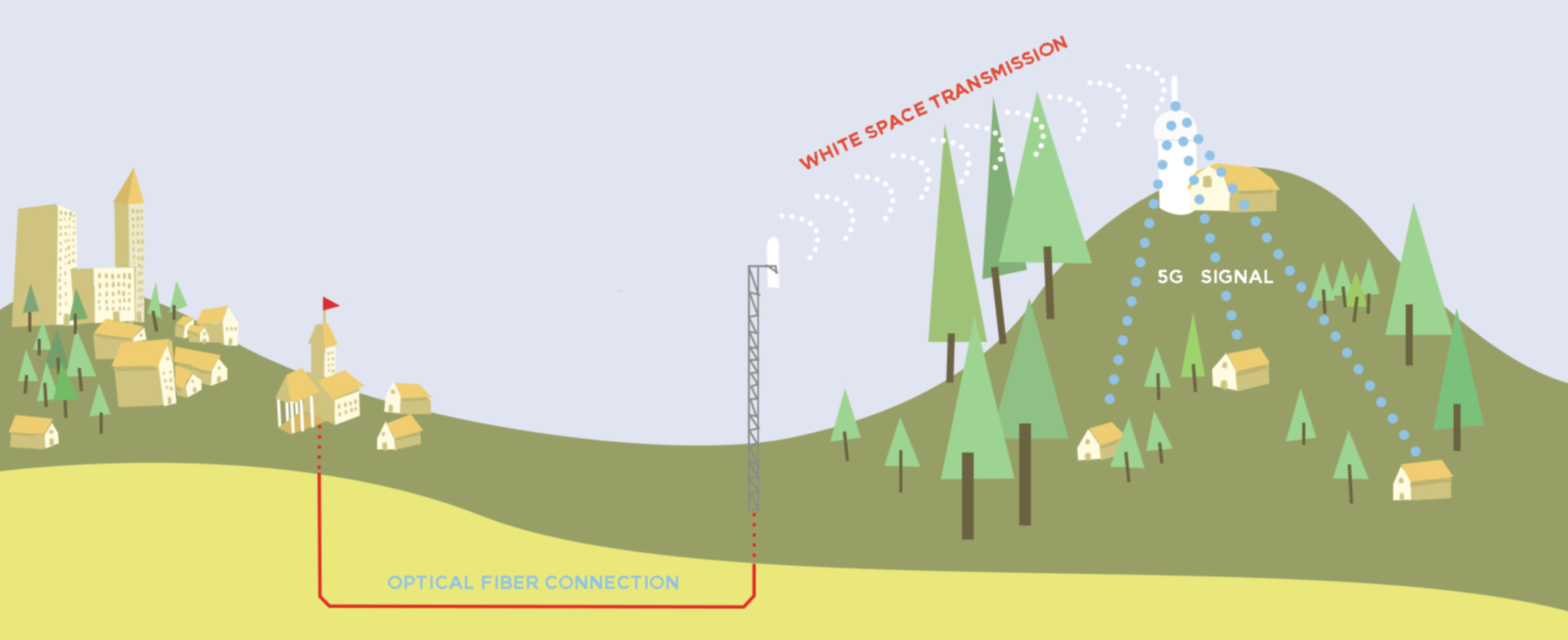

One of those resources was unused TV channels. Known as white space, a lot of the frequencies that previously broadcast analog channels are no longer used, since stations have switched to digital, which requires less spectrum space. All these unused “channels” can act like Wi-Fi extenders, bringing internet to further reaches. Basically, if you could get the local TV news back in analog days, you can get the internet to your door now.

In Garrett County, this was a huge asset, according to Nathaniel Watkins, the chief information officer for the county government. Due to the county’s geography, there were multiple unused channels available that weren’t being broadcast on and that weren’t getting any bleed over from other cities.

“We’re kind of protected on all sides by mountains,” Watkins said. “In rural areas, we’re super fortunate because there aren’t a lot of TV broadcasters that are bleeding over into those channels.”

White space is particularly useful because it’s transmitted on low-frequency waves, meaning it doesn’t need a direct line-of-sight from the transmission point to the receiver. It can reach through trees, hills, and buildings, making it ideal for rural areas. The FCC recently approved the use of channel bonding, where multiple consecutive channels are lumped together to create a larger bandwidth, something Garrett County quickly took advantage of.

But while whitespace enabled a lot of the internet expansion in this corner of Maryland, it was only one tool the county has been using. When there is direct line-of-sight—if a community has a tall hill in the center where a tower can be built, for example—using a 5G wireless system can provide better results. To get these hubs in as many places as possible, the county government started looking for anything tall enough to stick an antenna on.

“People have allowed us to put antennae on barns, silos, the sides of houses,” DeBerry told me. “There are antennae on trees. We’ve got folks willing to put in poles [on their property] for us. They’re just desperate for service and willing to help their neighbors get it as well.”

Often, a combination of techniques is used: fiber connection from the county seat can feed to a tower, which transmits several miles via whitespace to a smaller tower on someone’s barn, which shoots 5G signal down to all the neighbors. For $75 a month (comparable or less than a satellite internet subscription), residents can get 5mbps download and upload speeds with no data caps and much more reliable services.

DeBerry said while the county government has a private partner working on these projects, it’s not trying to compete with the local ISPs that have been serving the area. They’ve worked with these businesses to extend their service as well, tasking county summer workers with digging trenches so the companies can expand another mile to reach an unserved area.

“We just recently completed a project for that, and a cable company is now able to provide service for 25 new homes and businesses because we helped them get the infrastructure there,” DeBerry said.

In the last year, more than 150 new homes and businesses gained access to high-speed internet through the program. There are still plenty of people without access, and with the exception of those who don’t want internet (like the local Mennonite and Amish communities), DeBerry said she believes they can one day get everyone hooked up.

“I’m hopeful we can reach most of those people even out in the middle of nowhere,” she said. “We’re trying to get everybody.”

AHEAD OF THE CURVE

Coshocton County, Ohio

“Enjoy your visit to Coshocton,” said a high schooler after I snapped some photos of the flag team practice.

She wasn’t quite sure why a reporter would come to this sleepy corner of Ohio, with its winding country roads, corn fields, and population of 11,000. But when I told her I was reporting on rural broadband, a look of understanding washed over her face. After all, for the last seven years, a high-speed internet transmitter has topped the student radio station tower on the hill across from River View High School, beaming lightning fast internet into the school and surrounding homes.

It’s the product of a long-term project spearheaded by a local politician. In 2006, Gary Fischer was the mayor of Warsaw, Ohio (population 800), and decided to run for a commissioner seat. It was the first time he had realized the area’s digital divide.

“We had great internet service in Warsaw, so I didn’t realize it was an issue until I started campaigning county wide,” Fischer told me.

It quickly became apparent that many people in the county’s rural stretches lacked any internet access—more than 4,000 households were unconnected. The only option they had was satellite service, which was slow (1 to 2 mbps), spotty (bad weather, or even a breeze, could knock out a signal), and expensive ($75 to $80 per month in 2006, according to Fischer). He wasn’t sure how, but he told voters he would work on fixing the problem if he got elected. Fischer took office on January 1, 2007.

That spring, a member of the county’s IT department returned from a conference bearing a napkin scribbled with ideas. It was Fischer’s first glimpse at a solution; A private-public partnership could help set up infrastructure to expand broadband and deliver wireless signals to pockets across the county. But the private company, Lightspeed Technologies (now owned by Watch Communications), didn’t want to foot the bill for putting up dozens of towers. It needed “vertical infrastructure,” Fischer said. So he went hunting for the tallest things in the county.

First the county identified huge state-owned radio towers that transmitted Ohio’s Multi-Agency Radio Communication System (MARCS), which is used by emergency services. Coshocton asked the state if it could lease some space at the top of these towers to put up broadband antennae. While the state mulled it over, the county looked for more towers: the local 911 radio towers, the water towers, the radio station at the high school.

“Then we started to broaden our horizons a little bit,” Fischer told me. “We’re in a farming community. We’ve got 100 foot silos all over the country. That’s as good as a 100 foot tower.”

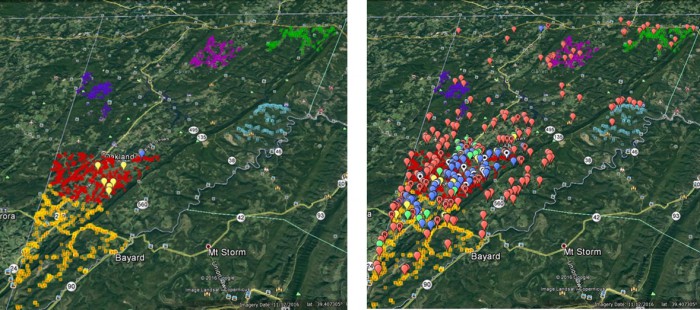

Eventually, the state gave the greenlight to lease the MARCS towers, and Coshocton secured a $38,000 grant from the Appalachian Regional Commission. It used that money to offset the costs of leasing the towers while the local provider set up shop. Over the next six years, 16 towers were raised—on top of barns, on MARCS towers, on water towers—to deliver high-speed internet to the county’s most rural residents.

Each tower took some creative engineering. The village of Walhonding, for example, is located in a hollow that blocked the signal from the closest MARCS tower in Newcastle, just three miles away. County surveyors went in, identified an ideal location, and knocked on the door of a Walhonding resident.

“They said, ‘We’ll give you free internet service if you let us put a tower in your backyard,'” Fischer said. “He was happy to do it. Now we have 20 or 30 households in Walhonding that are connected.”

Though the county government still works as a middleman—it leases the local 911 towers to the ISP, and subleases the state towers—it has spent very little beyond that first $38,000 grant (Fischer said the county invested about $10,000 in lawyers fees to draw up all the contracts). The user fees keep the system entirely self-sustaining, and profitable for the private ISP.

Between 2008 and 2011, the percent of Coshocton County residents with broadband internet at home rose from 32 percent to 58 percent, according to Connect Ohio, and they were paying less than the state average. The latest map shows a significant coverage area, though there are still pockets of unserved communities. Fischer said he knew from day one that the county wouldn’t be able to reach all 4,000 households in the short term.

These days, Fischer plans to start a campaign to inform small communities of how to lure the local service provider. If just seven households can all agree they want internet and one of the homeowners puts a tower in their yard, or on top of their silo, it would make it worthwhile for the ISP to bring in service. He said the proof of concept has reached the point where it’s a lot easier to expand than in the initial parts of the project.

“A lot of people said this would never work, but we’ve been up and running since April of 2009,” Fischer said. “It’s here. It’s proven.”

Back on that hot day in June, I managed to find the cemetery and the barn outside of Coshocton, just as Shryock had instructed. No one was home when I knocked and, as horses eyed me from a nearby paddock, stared up at the antenna on top of that big blue silo. I know now that it beams high-speed internet to the farmhouse next door—for free, since the family graciously provided the silo—and to dozens of neighbors up and down the hollow, including another farmer down the road, who waved at me from his tractor as I drove past on my way back to Brooklyn.

Get six of our favorite Motherboard stories every day by signing up for our newsletter.