Mutant Yippies, LSD, and Cyberpunks: The Story of the Space Age Newspaper ‘High Frontiers’

Credit to Author: Roisin Kiberd| Date: Fri, 11 Aug 2017 15:48:23 +0000

“The space age newspaper of psychedelics, science, human potential, irreverence and modern art”

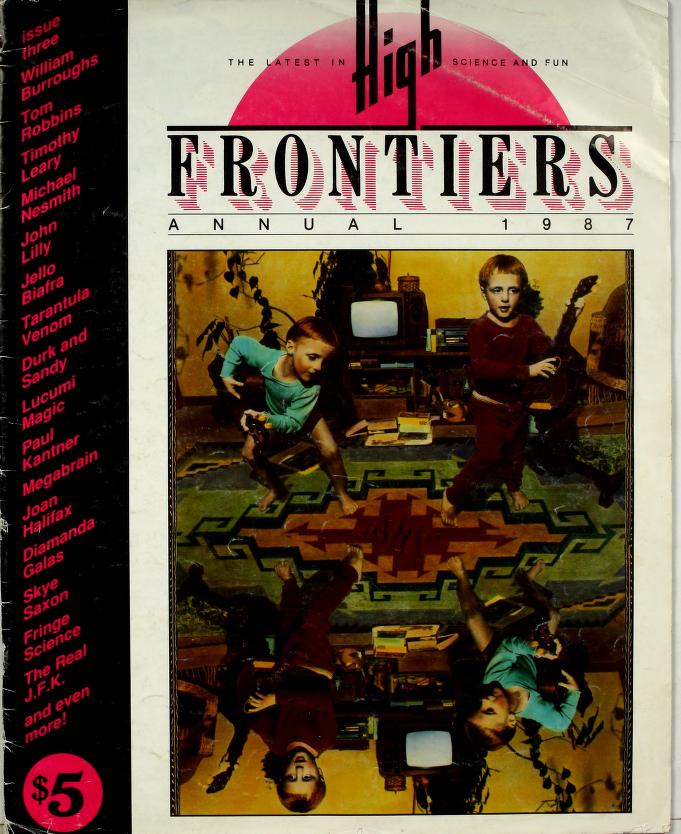

— The header on the front page of the first edition of High Frontiers. Distributed in early 80s San Francisco, the first edition was a DIY affair, but it launched with a deep-rooted sense of cosmic purpose.

Thirty-three years ago, a sometime punk, occasional Yippie, and full-time internet weirdo—the godfather of all internet weirdos, perhaps—R U Sirius, known IRL as Ken Goffman, founded High Frontiers, the San Francisco-based publication which would later be known as Mondo 2000. Sirius’s CV is extravagant and varied: at various times he has edited technology journals, appeared in arthouse cinema, created music with a band named ‘Mondo Vanilli,’ hosted podcasts, and at one point co-authored a book with psychonaut philosopher Timothy Leary*, despite the latter’s death halfway through the project (1998’s fittingly titled Design for Dying). In the year 2000, Sirius also ran for president, with the campaign line “ Victory over horseshit! Mock the vote!“

Today, however, we are discussing that first “space age newspaper,” an irreverent yet idealistic project which began when Sirius put out a call for contributors in a San Francisco newsweekly. Speaking to Motherboard over Skype, he explained: “I moved from upstate New York to Berkeley on my own in 1982, with the intention of causing the total transmutation of everything thanks to an LSD trip on the night that John Lennon was shot.”

“We really had to work to convince people that technology was defining the future. Nobody really got it.”

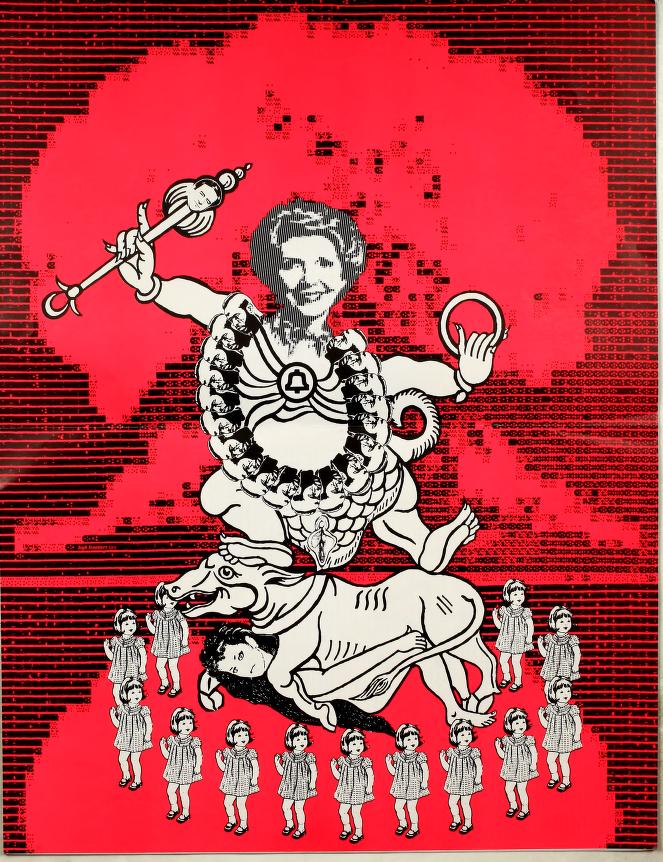

The first issue appeared in 1984, featuring Leary, Terence McKenna, and Bruce Eisner, along with the erratic yet intricate visual style that would evolve in future issues.

Half the appeal in reading through old editions, preserved today on Archive.org, stems from the paper’s bizarre details: the stamp on the cover, claiming High Frontiers to be the “official psychedelic newspaper of the summer Olympic games,” or the ad inside for a company called ‘Pyravid International’ selling subscriptions to the ‘Brain Mind Bulletin.’

There are ads for nonsensical inventions straight out of an episode of Rick and Morty. There are comics making fun of Yuppies, talk of early nootropic brain enhancement and life-extension, and the assertion that ‘science without feminism is apocalypse.’

In one tiny panel placed in the corner of one page, a company showcases mail-order t-shirts emblazoned with the slogan “ Let’s get meta-physical.” Elsewhere, an apparently inexhaustible succession of publishing houses advertise guides to growing marijuana, while a man named “Jeff Abbott, Computer Therapist” claims to have “over EIGHT YEARS facilitating human/computer relationships.” He signs off with “WHEN THE CHIPS ARE DOWN, CALL JEFF!”

All this is in the first issue alone, which Sirius speaks of almost dismissively: “Despite being a pretty ratty-assed first issue on newsprint, which we mostly gave away for free, it got a pretty good response.”

By the second issue they’d upped the ante, with a day-glo pink, 11×17 cover image of satirical cult leader Bob Dobbs, along with a Mickey Mouse acid tab bearing the CIA insignia and the phrase “Kids Do the Darnedest Drugs!” ( High Frontiers is full of in-jokes, the “ideas, datum, erratum” promised on its cover page). Gradually Sirius gathered a collective of writers, artists, thinkers, and experimenters, often centred around a restaurant called Flashback Pizza

“There was a whole bunch of freaks hanging out there every night,” Sirius said. “Nobody ever came in for pizza. The average person would get within a half mile of the place and feel the insane vibes and find their pizza elsewhere…”

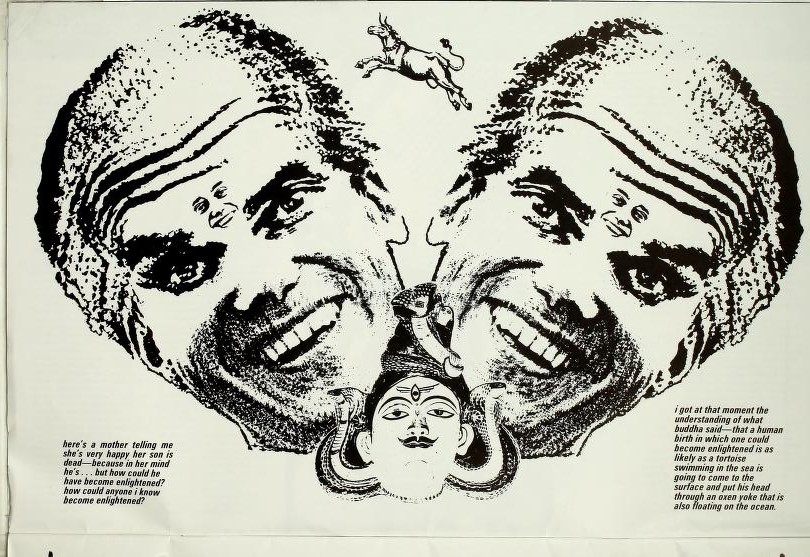

While psychedelic experimentation was writ large as the theme of High Frontiers, technology was never far from its pages. “It was my idea to merge psychedelics and emerging technologies, and the culture around technology,” Sirius said, citing Timothy Leary, writer Robert Anton Wilson and counterculture magazine The Whole Earth Catalog among his inspirations.

“William Burroughs was also an advocate of high technology, and the ‘brain machine,’” he continued. “I kind of found my way into that particular stream of bohemian culture. It was probably a minority, but there had always been that idea of letting robots replace human work.”

Read More: Universal Basic Income Is the Path to an Entirely New Economic System

Soon High Frontiers evolved into a glossy magazine, Reality Hackers (“Some distributors at the time thought it was about hacking people up, and put it on the shelf next to murder mystery magazines”) , and later Mondo 2000, which ran from 1989 till 1998. The word ‘mondo’ was an interesting choice—the Mondo movies of the 60s, 70s, and 80s showcased ‘shockumentary’ footage from around the world on video.

“We don’t really like sharing each other’s brains, as it turns out. They’re not well-developed.”

Mondo 2000 spoke to a magpie taste for cultural writing, irreverent humour and surreal design, blending countercultural values with a pre-millennial mix of anxiety and awe, auguring in the 21st century chaos with writer Bruce Sterling would later call ‘dark euphoria.’

In High Frontiers and its inheritors, the word ‘mutation’ appears again and again. Archive.org even hosts a flier dating from 1985, advertising a ‘World Mutation Day’ event organised by magazine and its acolytes. It’s a distinctly Cronenberg-y take on personal enlightenment. (When I tell Sirius this, he mentions that he once actually interviewed David Cronenberg for Wired. Apparently Kathy Acker was also meant to turn up, but sadly couldn’t make it.) High Frontiers documents life with ‘the new flesh,’ a culture placed somewhere between the Summer of Love and techno-utopianism.

What began as a fringe movement gravitated slowly toward the cultural mainstream. Wired magazine appeared in 1993, and cyberpunk became a buzzword as a genre of fiction and an aesthetic. However, not everyone was convinced.

“Touring for the Mondo 2000 book in 1993,” Sirius said, “we really had to work to convince people that technology was defining the future. Nobody really got it. Doug Rushkoff wrote his book Cyberia, and his first book company cancelled its publication because they said the internet was a fad and that it would be over by the time the book came out.”

Parts of High Frontiers read as familiar to readers in today’s Trump era—in Sirius’s editorial for Issue One, he argues for distribution of wealth and conservation of the planet, and criticises then-president Ronald Reagan as “our absurd, grade-b movie-star president, Armageddon Man.” Other passages are movingly Utopian, describing a hope for harmony among mankind aided by technology and psychedelic medicine.

The word ‘acceleration’ appears frequently, too, and today Sirius stands by the belief that technology cannot be halted, but it can be turned to address urgent threats like climate change: “We’re not going to dial it back. The communication aspect of it, the idea that people would all be united in a global brain which will be harmonious… that was a big theme in those days, in particular with Mondo 2000. But we don’t really like sharing each other’s brains, as it turns out. They’re not well-developed. They’re kind of nasty. Personally, I think material technologies, amplified by a network of access, will be more helpful to humankind.”

Finally, there’s the idea of subversion, the punk influence, and the absurdism that characterises High Frontiers and its descendants. This humour lives on in Weird Twitter and its adjacent ‘Dirtbag Left’, but has also been very visibly co-opted by the alt-right. “It has become much stranger, and more extreme,” Sirius agreed. “It’s not so much the rhetoric of High Frontiers and Mondo, in terms of psychedelics and technology, but in terms of the pranking and the attitude, the Operation Mindfuck, all those things which were so important to us in the past. It’s quite peculiar to see them being used by White Nationalists now.”

There is something inherently dystopian about our internet, when compared to that imagined in High Frontiers’ pages. “Everybody is complaining now on social media. There’s a darkness to it,” Sirius said. “I post every few months on my Twitter account, ‘What is the sound of a billion knees jerking?'”

While he uses Facebook and Twitter, Sirius is critical of their role in colonising what was once a more democratic and open space. “People being are being herded into little buildings—or huge ones—in what was supposed to be a wide open space in which everybody created their own sites. It’s a complete corporate takeover of the net, Facebook in particular… It it’s definitely not what we were expecting.”

Still, Sirius retains a certain optimism, a sense that we’ll find a way through the noise. Recently he began posting a mixture of old and new writing to Mondo2000.com, and posts to Twitter under the name ‘Steal This Singularity‘, promoting an ethos half-Kurzweil, half-Abbie Hoffman, which he envisions playing a role in humanity’s future. “There’s the old Jefferson Starship line, from the 70s, ‘ Hijack the starship’. But someone has to build the starship first in order for you to hijack it…”

In this sense, High Frontiers remains ahead of its time. For now it lies dormant as a record of techno-utopian thought, awaiting its purpose in coming years as a manual for space-age sedition. If— when—the Singularity awakens, perhaps we’ll be ready and waiting to steal it.

*Correction: A previous version of this article incorrectly stated Terence McKenna as co-author, not Timothy Leary. Motherboard regrets the error.

Get six of our favorite Motherboard stories every day by signing up for our newsletter.