Big Tech Has Destroyed America’s Sustainable Electronics Standards

Credit to Author: Jason Koebler| Date: Thu, 03 Aug 2017 17:27:21 +0000

It’s not easy to repair a Galaxy S8. Opening up Samsung’s flagship phone requires heating the device to loosen the glue that holds it together and cutting and prying through that adhesive.

Still, the Galaxy S8 earned a “gold” rating from the nonprofit Green Electronics Council under its Electronic Product Environmental Assessment Tool (EPEAT) certification—the only meaningful environmental and sustainability certification for electronic products in the United States. “Extension of useful life”—meaning repair and refurbishment—is a key component of these standards because environmental experts agree that fixing a broken phone is much better for the Earth than buying a new one.

That the Galaxy S8 was able to earn the highest possible EPEAT rating confirmed what many involved in the actual development of those standards already knew: America’s green electronics standards have been taken over by the most powerful gadget manufacturers in the world and have been watered down to the point where they are largely meaningless.

“It’s crazy to me that phone got that rating,” Mark Schaffer, who managed environmental programs at Dell and is now an independent electronics life cycle consultant, told me on the phone. “It’s sad to me to see a brand new standard come out that’s meant to show environmental leadership and see a phone like that get gold. It’s too damn easy.”

Schaffer has been on every major EPEAT standards development board for the last 14 years, including the mobile phone certification standards development board. He’s the author of a report released Thursday that claims electronics manufacturers including Samsung and Apple have “consistently opposed stronger reuse and repair criteria,” turning EPEAT certifications into a “complicated way for manufacturers to greenwash products that have a devastating environmental impact and pat themselves on the back for business as usual.” The report was released by Repair.org, a trade organization made up of small businesses that is fighting for “right to repair” laws in states around the country.

After seeing an early copy of Schaffer’s report, I spoke to four other environmental experts who have spent years of their lives working on certification standards for every major type of electronics. All of them emphatically said that environmental progress has stalled because electronic companies have rigged the standards development process to the point where real progress is impossible; two of the people I spoke to have pulled their nonprofit organizations out of the process in protest. When a coalition of nonprofits, academics, and environmentalists attempted to use a different standards-making process for computer server standards, every major manufacturer boycotted the new system and forced a return to the old one.

Even Nancy Gillis, the CEO of the Green Electronics Council that administers EPEAT, told me that many of the EPEAT standards are outdated and that many of the standards no longer serve their initial function, which was to create environmental competition among companies. For example, nearly every new laptop that’s released earns EPEAT’s gold award. “It’s EPEAT’s publicly stated goal to have only a third of the products even be able to attain a bronze,” Gillis told me. “But almost everything is gold now because the standards have been static.”

A “Multi-stakeholder process” dominated by giant companies

Besides repairability, EPEAT standards—which exist for mobile phones, televisions, servers, desktop and laptop computers, and printers, copiers, and scanners—generally take into account things like recyclability, energy use, and use of conflict minerals.

When it was released for laptops and desktop computers in 2006, just 60 products attained bronze or silver status. No product attained gold status. This was by design: “Gold was truly an aspiration driver for redesigning products,” Sarah Westervelt, policy director of the e-Stewards electronic waste recycling standards (the strictest and most widely respected recycling standard in the US) and a longtime member of various EPEAT standards boards, told me.

“They’ve shifted the whole bar lower so that all of them or most of them can achieve gold status quite easy”

The standards do not have the force of law behind them—no manufacturer is required to get EPEAT certified. But the original EPEAT standards for computers were developed with the help of the Environmental Protection Agency, and President George W. Bush issued an executive order in 2007 mandating that 95 percent of all electronics purchased by the federal government be EPEAT certified.

After that executive order, not being EPEAT certified could mean losing out in millions of dollars in government procurement contracts. Because certification suddenly mattered to their bottom line, electronics manufacturers had an incentive to not only attain gold status, but to make attaining gold status as easy as possible.

“They’ve shifted the whole bar lower so that all of them or most of them can achieve gold status quite easy,” Westervelt said.

The EPEAT system is quite convoluted, but the quick version of how it works is like this: The Green Electronics Council invented and administers EPEAT, which is a set of standards. But the standards development process is not done by GEC. Instead, their development is overseen by standards development organizations, or SDOs, which themselves must be accredited by the American National Standards Institute. GEC uses three SDOs: The Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Standards Association (IEEE-SA), NSF International (unrelated to the National Science Foundation), and UL, a safety consulting and certification company. Each of those SDOs has its own process for how standards should be developed, but each SDO uses a consensus-based multi-stakeholder system.

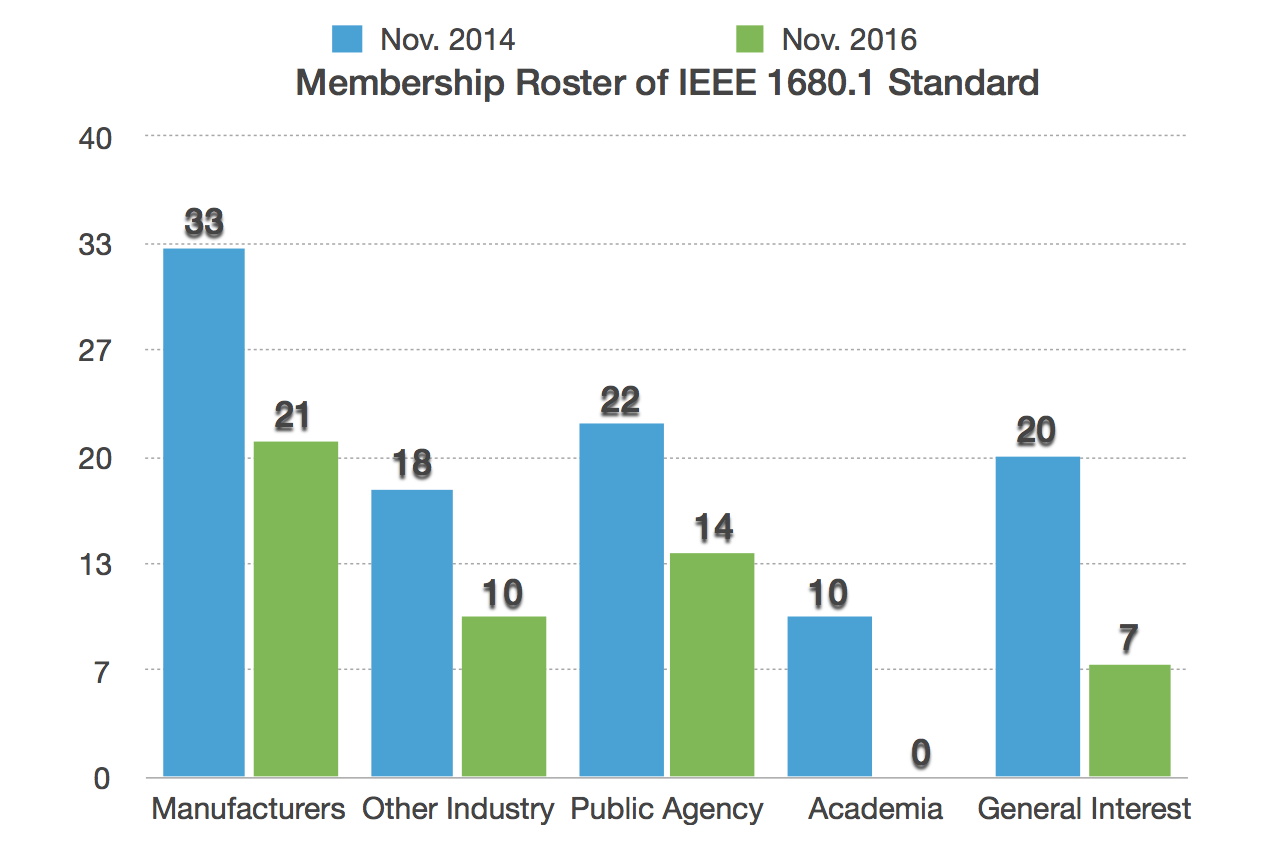

In the case of IEEE-SA, there are five categories of stakeholder: “manufacturer,” “other industry,” public agency,” “academia,” and “general interest.” These stakeholders are supposed to sit in a room, come up with the standards, and vote on them. But increasingly, representatives for the manufacturers are the ones who control much of the process. In IEEE-SA development, there are few limits to the number of people who can participate or vote in the process.

“The IEEE-SA is committed to inclusivity. Everyone can join. Everyone can participate,” a spokesperson for IEEE-SA told Motherboard in a statement. “We are open in membership, in participation and in governance—no matter your market around the world, your industry or the size of your company. Anyone is welcome to participate at any level.”

That sounds good in theory, but people involved in the process told me that the open membership hasn’t done much to stop manufacturer dominance of the standards development, and in fact has helped facilitate industry dominance as many manufacturers list their representatives as “other industry” and “general interest” members.

“Members select their own category assignments. As a result, manufacturers often list members in the general interest category, as well as in the manufacturer category,” Schaffer wrote.

In theory, “manufacturers” are limited to having 50 percent of the vote. But there are few lines between “manufacturer,” “other industry,” and “general interest.” On the EPEAT computer standard’s public roster (available in the report), for instance, Apple, HP, and Lenovo have four members each and Dell has five members; Lockheed Martin has two “general interest” members, and Cisco, Blackberry, and Intel are considered “other industry.” For the EPEAT server standard, however, Apple and Microsoft are considered “other industry,” while Cisco is considered a manufacturer.

“While participants may represent the interests of their employers, individual members participate in the process and ballot as individuals, rather than as a corporate entity,” IEEE-SA told me. “Each individual has one vote, or each entity has one vote—either way, the IEEE-SA is predicated on balance and fairness.”

In procedural votes, “you sometimes have 20, 30 people voting for one company,” Westervelt said. Total vote tallies vary, she and others on the committees told me, because there are different types of votes throughout the process—official votes on standards in the IEEE-SA process limit manufacturers to one vote, but votes during the process are less formal and so suggested standards can be killed before they move to this final vote.

“We can’t move forward with a different standards process without having a balanced set of stakeholders. If some people don’t want to play, our options are limited.”

“They just have many more people at the table,” Barbara Kyle, founder of the Electronics Takeback Coalition, which promotes green design, told me. “They have as many people at the table as they want and they have up to half the votes. And then there’s industry groups that get some more votes. The people that represent the public have almost no votes.”

For example, a comparison of public rosters of people working on the EPEAT computer standards between November 2014 and November 2016 shows that members of academia and nonprofits disproportionately dropped out of the computer standards development committee; there are currently no academics working on the standards (there were 10 in 2014), and there are only two members from the nonprofit world—both of whom work for GEC, the group that invented the EPEAT. Industry, meanwhile, has 31 members working on that standard, which hasn’t been updated since 2006.

Standards that don’t mean anything

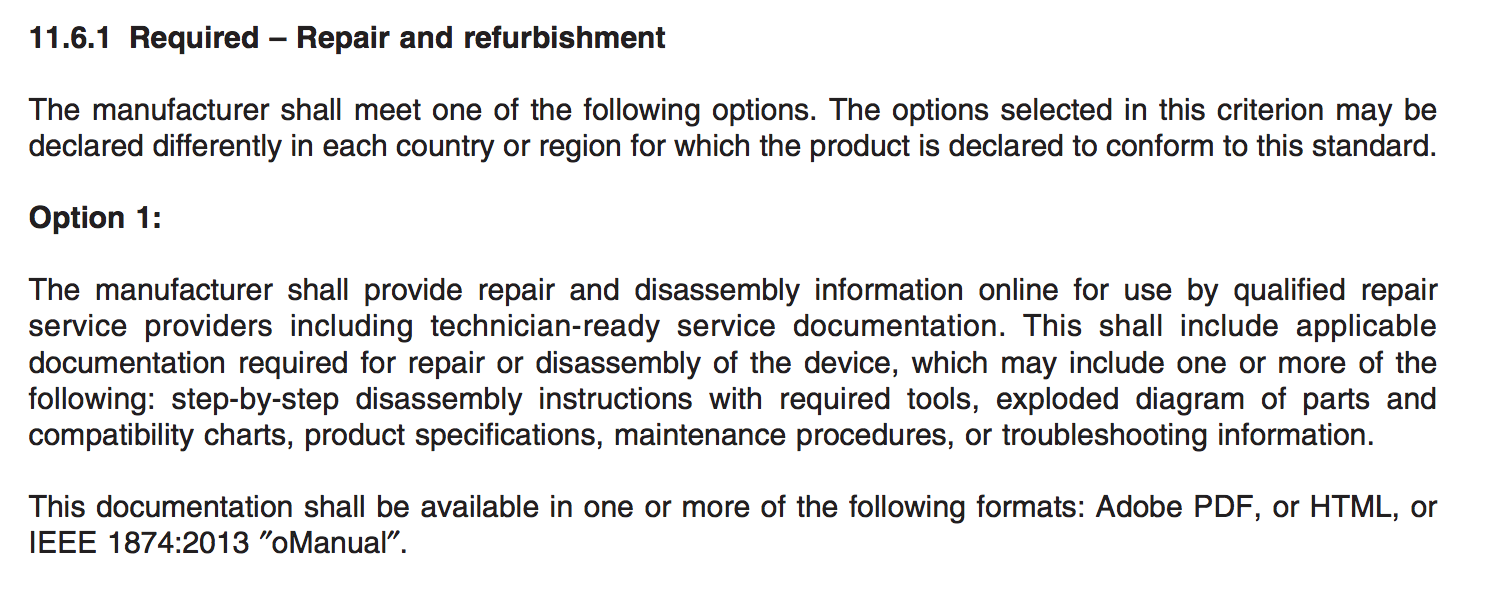

The new EPEAT standards for cell phones—which are not public but were acquired by Motherboard—have requirements that seem designed to force manufacturers to design and support repair, but have loopholes that make them easy to comply with. For instance, in order to get even a bronze EPEAT rating, manufacturers must do any one of the following:

– Publish repair guides online

– Give repair guides to third-party repair centers that meet separate third-party requirements

– None of those two things; simply having “one or more manufacturer-authorized service centers” is enough to meet the requirement. For example, this means that the mere existence of one Apple Store—anywhere in the US—is enough to satisfy this requirement for the iPhone. Apple (nor any other major phone manufacturer) actually publishes phone repair guides online.

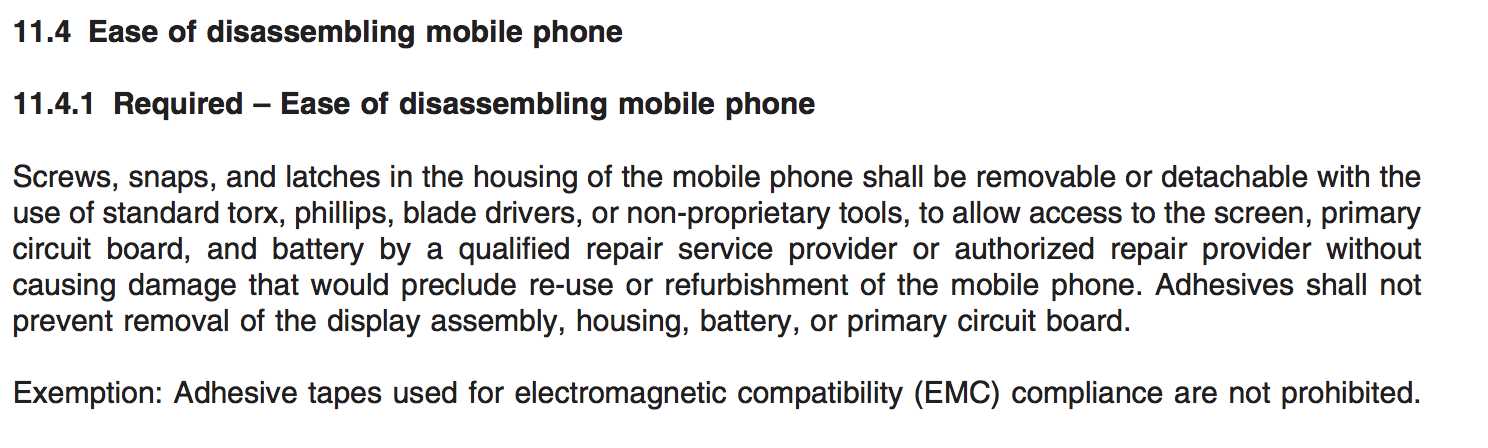

Even requirements that seem strict don’t seem to be enforced. The standard states that “ease of disassembling mobile phone” is a requirement, meaning someone should be able to take it apart using “non-proprietary tools,” which is any tool that is “legally available for purchase by the general public.”

Last year, I obtained a copy of Samsung’s internal repair guides that it sends to its authorized repair centers. Here are the tools Samsung suggests its repair techs use to open the Galaxy S7, which is slightly less repairable than the gold-certified Galaxy S8, but not by much:

This single slide lists three tools that a reasonable person would consider “proprietary”—the hot plate, and two disassembly holders (which hold the phone in place) are not widely available and their existence is not generally known to the average person. They can indeed be purchased online through quasi-official sources—the hot plate costs $700, one disassembly holder costs $242, and the other costs $284.

“Any cell phone standard that doesn’t do a good job addressing repairability is not a good standard,” Kyle told me. A 2013 paper from IEEE noted that extending the life of a cell phone from one to four years “decreases its environmental impact by about 40 percent.”

UL, which developed the cell phone standard, told me in a statement that it sought out a balanced process:

“Our standards technical panel (STP) serves as the consensus body for standard development, and is made-up of a balanced group of consisting of manufacturers, supply chain owners, commercial/industrial users, regulators, government officials, consumers and international delegates,” a spokesperson at UL told me. “The [cell phone] standard that is now on the EPEAT registry was developed by a balanced STP comprised of 30 members, of which no interest category was over 27 percent of the total STP. In addition, public review comments were submitted and addressed as part of the open consensus process.”

“We realized this isn’t ever going to result in true sustainability, and manufacturers are going to rubber stamp whatever they want. We just weren’t going to do it anymore.”

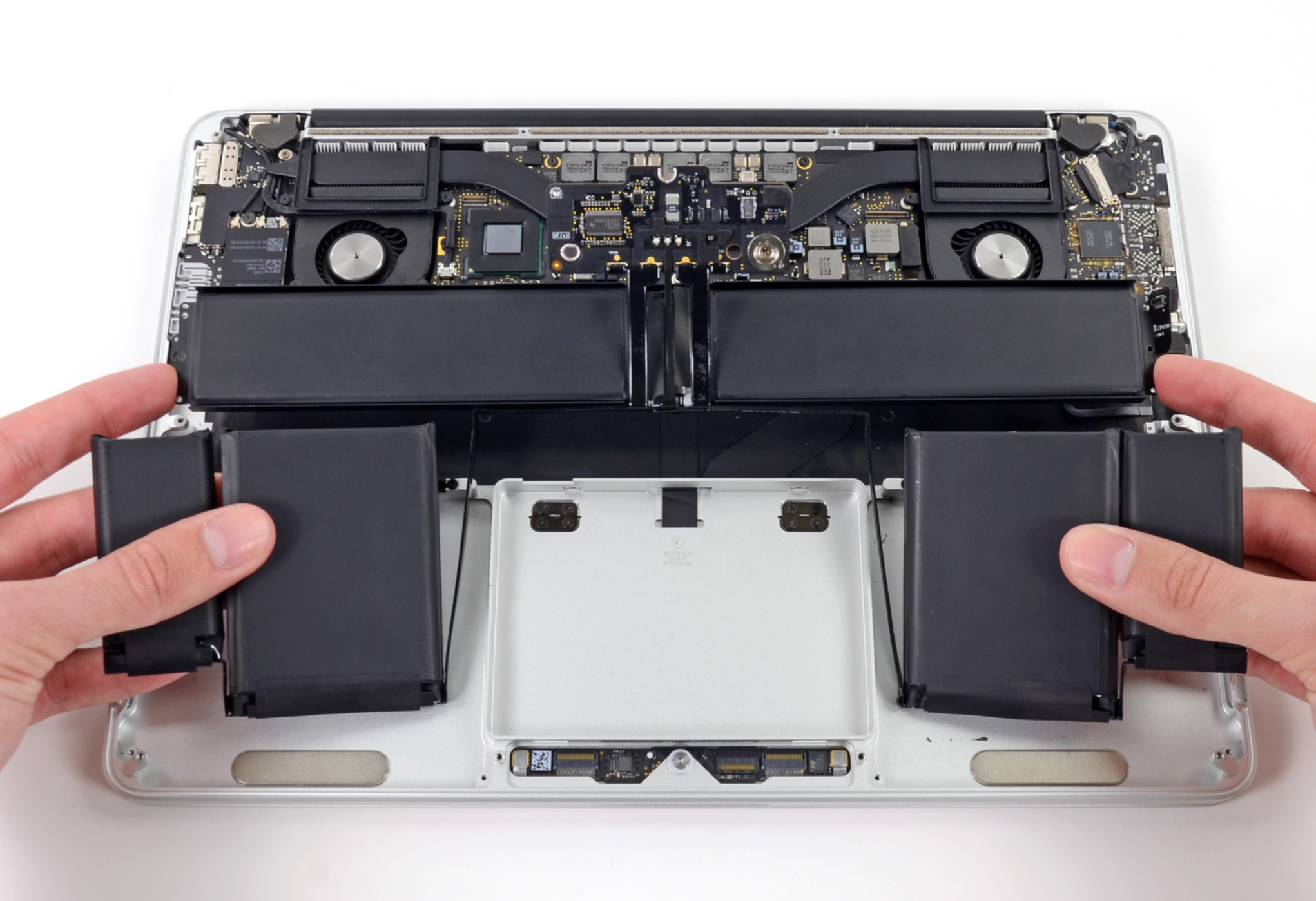

How the Galaxy S8 passed the EPEAT test is a mystery to several repair experts and standards designers I spoke to. It was reminiscent to them of the time the 2012 MacBook Pro Retina got EPEAT gold certification, despite the fact that it is neither modular (a requirement of the standard) and has glued-in batteries that are tough to remove for recycling.

“Every product since then hasn’t improved the design and they’re still certified as gold,” Schaffer told me. “That incident [the MacBook Pro getting gold] set a precedent. Apple, HP, Dell—they can now all claim it.”

Apple and Samsung did not respond to request for comment.

A process that bleeds nonprofits dry

Even without obstruction, getting consensus on standards is a long and arduous process. Manufacturers—who can have millions of dollars on the line—have no incentive to speed up the process and can afford to continue to send representatives to meeting after meeting, year after year.

“Government and NGOs don’t have the funding to spend years and years on these processes,” Kyle said. “People are just not interested in funding something that takes five, seven years. It doesn’t look to donors like their money is well-spent, even if it’s impactful in the long run.”

Kyle pulled her organization out of the process altogether after years of being frustrated by manufacturer roadblocks in the development of green television standards, which were released in 2012: “We’ve been through the battles for years and years and years and it’s not a fair fight,” she said. “We realized this isn’t ever going to result in true sustainability, and manufacturers are going to rubber stamp whatever they want. We just weren’t going to do it anymore.”

Westervelt similarly pulled her organization—the Basel Action Network, perhaps the most well-respected e-waste group in the United States—out of the standards-making process after the TV experience.

“The four or five NGOs participating would spend years wordsmithing technical language, carefully crafting these texts, and they would just get voted down with no explanation,” Westervelt said. “We don’t have a line item to hire people to vote on our behalf like they do. We said we’re never going to participate again unless the process changes.”

All Gold Everything

What we’re left with, then, are green standards that were once progressive but are now outdated. We’re left with standards that are written with enough wiggle room that almost anything that hits the market can likely be certified as “gold.”

“The way it is currently done has run its course,” Willie Cade, founder of PC Rebuilders and Recyclers and an environmental consultant who has worked on many standards boards, told me. “There’s still small incremental value to it, but we need new standards that have some real muscle behind them.”

Manufacturers boycotted an attempt to reform the process

Even GEC, the group that invented EPEAT, feels hamstrung by what the process has become. Government procurement rules haven’t changed and EPEAT is still technically voluntary. This means manufacturers don’t need new standards, and are able to resist changes to the process. For instance: Over the last few years, NGOs attempted to change the computer server standards development away from an IEEE-led process to one led by the NSF, which has stricter limits on manufacturer voting. Across the board, manufacturers simply refused to participate in the NSF process, according to Westervelt, Kyle, and Sue Chiang, pollution prevention director at the Center for Environmental Health.

“When we succeeded in getting the next server EPEAT standard moved to NSF, none of the manufacturers showed up at the table,” Westervelt said. “Not a single one.”

NSF told me in an emailed statement that its process is “designed to withstand scrutiny, while protecting the rights and interests of every participant.”

“I think everyone agrees how it’s working right now isn’t working—it’s not fast enough,” Gillis of the GEC said. “But we can’t move forward with a different standards process without having a balanced set of stakeholders. If some people don’t want to play, our options are limited.”

In speaking to people who worked on the standards, I was continually met with exasperation; the EPEAT was designed to be an aspirational thing. Now it’s a checkbox. Gillis says she thinks the rating system still has value, but is holding out hope that new computer standards—which haven’t been updated since 2006—set to be published in 2018 will show a good-faith effort from manufacturers to push the envelope.

“I hope that standard gives purchasers the option of a lot of bronze, a few silver, and a tiny number, maybe no gold,” she said. “If it’s populated all by gold, then yeah—that standards development process isn’t serving us anymore. To me that’s a sign that EPEAT needs to think honestly—what does it do?”