Industrial robots are security weak link

Credit to Author: Sharon Gaudin| Date: Tue, 09 May 2017 03:00:00 -0700

Industrial robots used in factories and warehouses that are connected to the internet are not secure, leaving companies open to cyberattacks and costly damages.

That’s the word coming from a study conducted by global security software company Trend Micro and Polytechnic University of Milan, the largest technical university in Italy.

“The industrial robot – it’s not ready for the world it’s living in,” said Mark Nunnikhoven, vice president of cloud research at Trend Micro. “The reality is these things are being connected in more and more places. There are a lot of attacks that could happen in that environment.”

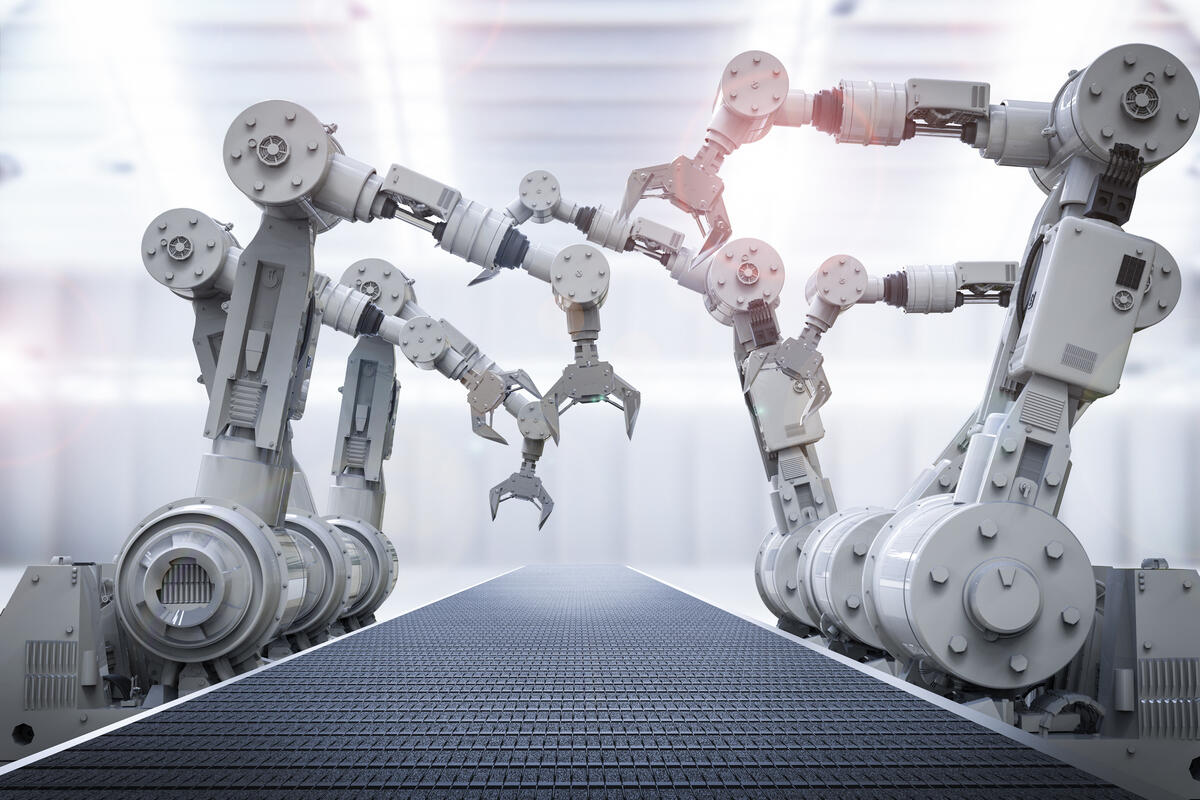

The study looked at Internet security vulnerabilities that could involve industrial robots used on manufacturing lines in areas such as the automobile and aerospace industries. The robots, which generally look like large mechanical arms, are used to move heavy objects, weld seams and fit pieces together. The machines also can be found moving and stacking crates in warehouses.

The issue is taking on greater significance as the use of robots grows in factories around the world. The International Federation of Robotics, in its World Robotics Report, said that 2.6 million industrial robots will be deployed worldwide by 2019, an increase of about 1 million since 2015.

While companies are careful to ensure that industrial robots are safe to work near people, they’re often not set up for cybersecurity. But these robots, according to Nunnikhoven, are increasingly being linked to company networks and the internet.

As long as there are proper security precautions, analysts said these robots can be connected to the internet. They need cybersecurity basics such as user names and passwords, two-factor authentication, encryption and hardware-based biometric authentication.

“I’m shocked that anyone would consider attaching anything to the internet without making sure it was secured,” said Dan Olds, an analyst with OrionX. “This applies to everything from home thermostats to big robotic arms. Everything attached to the internet is vulnerable to hacking.”

Patrick Moorhead, an analyst with Moor Insights & Strategy, said he was surprised that enterprises would forgo security on anything connected to the internet.

“The only thing I could attribute this to would be ignorance and maybe a way to save a few dollars here and there,” he said. “This could be incredibly dangerous. To protect the security of robots there should be protection all the way from the robot to the network to the data center. Data should be protected at rest and in flight. This means a secure chain of command, end to end, using encryption every step of the way as well as hardware-based biometric authentication all the way through the chain.”

Mike Gennert, a professor and director of the Robotics Engineering Program at Worcester Polytechnic Institute, in Worcester, Mass., said unsecured robots are the result of IT departments having to work with a new technology.

“It’s a whole other level of complexity in our systems,” Gennert said. “In the past, when you had a robot on a factory floor, it wasn’t part of a network that the outside world could view. There was a limited ability for malicious actors to connect with your robot. Now all these devices are on the internet and they’re all exposed.”

That means that companies will need to make sure there are IT managers, or even C-level executives, who can oversee robotics, making sure the technology is supporting the company’s business strategy while also making sure the machines are secure.

One challenge for companies will be to find people who have experience in both robotics and security. “There will be a few folks, but it will be a hot market because not many students study both robotics and security,” Gennert said. “Those that do both will be able to write their own ticket.”

Until companies can effectively combine robotics with security, robots may be an easy entryway for a hacker into a company’s networks.

Nunnikhoven said there’s no direct evidence that hackers have taken advantage of these exploits. There aren’t proper monitoring systems in place to know if the systems have been exploited, he said.

Malicious hackers could get into a robot’s controller system and make adjustments to its actions, which could create a dangerous situation in the factory or could enable the robots to build unsafe products on the production line.

Hackers also could gain access to the programming used to make the company’s products, or they could use the robot as a jumping off point to hack into other enterprise systems. Companies could fall victim to ransomware or sabotage.

“This is dangerous in several ways,” said Olds. “The first is pretty obvious — a hacker gets control of a robot and uses it to destroy company products or to hurt a human operator.”

“We looked at cybersecurity [because the robots] are being connected to larger networks and the internet itself,” he said. “During our research, the team found more than 83,000 of these robots exposed to the internet.”

Trend Micro got that number by running searches for about two weeks on Shodan, ZoomEye and Censys, search services that index data from internet-wide scans, looking for things like web cams, routers, servers and devices on the internet of things.

They then zeroed in on the industrial routers and robots that responded to their queries.

If the industrial robots responded, that meant they were not only connected to the internet but they were exposed. If secured, the robots wouldn’t be directly accessible from an unauthenticated random IP address querying them.

The robots’ responses also gave researchers the software version they were running, along with their manufacturer.

The study found industrial robots from five different vendors — like ABB Robotics, FANUC FTP, Yaskawa, Kawasaki E Controller and Mitsubishi FTP — and 12 of their brands of industrial robots. More than 80,000 of them are working in factories around the world.

Nunnikhoven said it’s unclear how many companies are operating these robots, but more than 10,000 of the machines are running in the U.S. The U.S., followed by Australia and Japan, were the three countries with the highest number of exposed industrial robots.

“It reflects the U.S. take on manufacturing,” said Nunnikhoven. “There’s a resurgence in trying to get smarter factories, and smarter factories would tend to have more industrial robots in play.”

According to the study, of the more than 83,000 exposed industrial robots, 59 had known vulnerabilities and more than 5,100 had no authentication.

So why would a company link an industrial robot working on a manufacturing line to the internet? Company IT managers might want internet access to robots so they could remotely adjust the robot’s programming or check the status of their factory lines.

“There is some logic to it, but a lot of warning flags too,” Nunnikhoven said. “People tend to look at the positive and the possibilities, and they don’t look at the risks. They say, ‘Hey, we can query from one central location or get status from manufacturing lines in real time, even though we’re manufacturing from the other side of the planet. This exposes you to significant risks.”

Nunnikhoven said the researchers worked in isolation — as opposed to a robot operating on a live factory floor. He said the researchers were able to hack into an industrial robot used for welding that had been set up like many typically are in factory situations. Once they had hacked in, the researchers were able to alter the robot’s configuration so it was no longer welding in a straight line.

“The robot has to be extremely precise,” Nunnikhoven explained. “Say, a [robotic] arm is doing a weld on a car line. It has to be very accurate to ensure the car chassis is strong enough to withstand impact and meet safety regulations. If they add a curve in [the weld], that’s a defect and that could be catastrophic when that car hits the road.”