Payments Giant Verifone Investigating Breach

Credit to Author: BrianKrebs| Date: Tue, 07 Mar 2017 18:02:30 +0000

Credit and debit card payments giant Verifone [NYSE: PAY] is investigating a breach of its internal computer networks that appears to have impacted a number of companies running its point-of-sale solutions, according to sources. Verifone says the extent of the breach was limited to its corporate network and that its payment services network was not impacted.

San Jose, Calif.-based Verifone is the largest maker of credit card terminals used in the United States. It sells point-of-sale terminals and services to support the swiping and processing of credit and debit card payments at a variety of businesses, including retailers, taxis, and fuel stations.

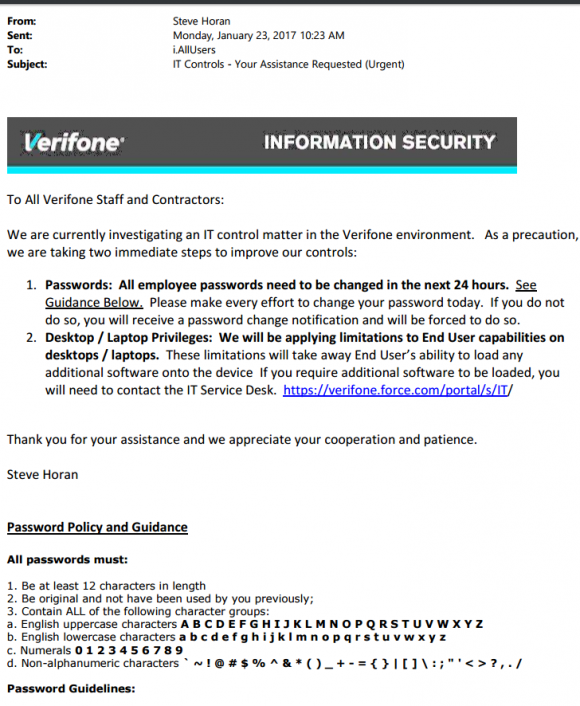

On Jan. 23, 2017, Verifone sent an “urgent” email to all company staff and contractors, warning they had 24 hours to change all company passwords.

“We are currently investigating an IT control matter in the Verifone environment,” reads an email memo penned by Steve Horan, Verifone Inc.’s senior vice president and chief information officer. “As a precaution, we are taking immediate steps to improve our controls.”

An internal memo sent Jan. 23, 2017 by Verifone’s chief information officer to all staff and contractors, telling them to change their passwords. The memo also states that Verifone employees would no longer be able to install software at will, apparently something everyone at the company could do prior to this notice.

The internal Verifone memo — a copy of which was obtained by KrebsOnSecurity and is pictured above — also informed employees they would no longer be allowed to install software of any kind on company computers and laptops.

Asked about the breach reports, a Verifone spokesman said the company saw evidence in January 2017 of an intrusion in a “limited portion” of its internal network, but that the breach never impacted its payment services network.

“In January 2017, Verifone’s information security team saw evidence of a limited cyber intrusion into our corporate network,” Verifone spokesman Andy Payment said. “Our payment services network was not impacted. We immediately began work to determine the type of information targeted and executed appropriate measures in response. We believe today that due to our immediate response, the potential for misuse of information is limited.”

Verifone’s Mr. Payment declined to answer additional questions about the breach, such as how Verifone learned about it and whether the company was initially notified by an outside party. But a source with knowledge of the matter told KrebsOnSecurity.com that the employee alert Verifone sent out on Jan, 23, 2017 was in response to a notification that Verifone received from the credit card companies Visa and Mastercard just days earlier in January.

A spokesperson for Visa declined to comment for this story. MasterCard officials did not respond to requests for comment.

According to my source, the intrusion impacted at least one corner of Verifone’s business: A customer support unit based in Clearwater, Fla. that provides comprehensive payment solutions specifically to gas and petrol stations throughout the United States — including, pay-at-the-pump credit card processing; physical cash registers inside the fuel station store; customer loyalty programs; and remote technical support.

The source said his employer shared with the card brands evidence that a Russian hacking group known for targeting payment providers and hospitality firms had compromised at least a portion of Verifone’s internal network.

The source says Visa and MasterCard were notified that the intruders appeared to have been inside of Verifone’s network since mid-2016. The source noted there is ample evidence the attackers used some of the same toolsets and infrastructure as the cybercrime gang that last year is thought to have hacked into Oracle’s MICROS division, a unit of Oracle that provides point-of-sale solutions to hundreds of thousands of retailers and hospitality firms.

Founded in Hawaii, U.S. in 1981, Verifone now operates in more than 150 countries worldwide and employ nearly 5,000 people globally.

Update, 1:17 p.m. ET: Verifone circled back post-publication with the following update to their statement: “According to the forensic information to-date, the cyber attempt was limited to controllers at approximately two dozen gas stations, and occurred over a short time frame. We believe that no other merchants were targeted and the integrity of our networks and merchants’ payment terminals remain secure and fully operational.”

ANALYSIS

In the MICROS breach, the intruders used a crimeware-as-a-service network called Carbanak, also known as Anunak. In that incident, the attackers compromised Oracle’s ticketing portal that Oracle uses to help MICROS’s hospitality customers remotely troubleshoot problems with their point-of-sale systems. The attackers reportedly used that access to plant malware on the support server so they could siphon MICROS customer usernames and passwords when those customers logged in to the support site.

Oracle’s very few public statements about that incident made it clear that the attackers were after information that could get them inside the electronic tills run by the company’s customers — not Oracle’s cloud or other service offerings. The company acknowledged that it had “detected and addressed malicious code in certain legacy Micros systems,” and that it had asked all MICROS customers to reset their passwords.

Avivah Litan, a financial fraud and endpoint solutions analyst for Gartner Inc., said the attackers in the Verifone breach probably also were after anything that would allow them to access customer payment terminals.

“The worst thing is the attackers have information on the point-of-sale systems that lets them put backdoors on the devices that can record, store and transmit stolen customer card data,” Litan said. “It sounds like they were after point-of-sale software information, whether the POS designs, the source code, or signing keys. Also, the company says it believes it stopped the breach in time, and that usually means they don’t know if they did. The bottom line is it’s very serious when the Verifone system gets breached.”

Verifone’s Jan. 23 “urgent” alert to its staff and contractors suggested that — prior to the intrusion — all employees were free to install or remove software at will. Litan said such policies are not uncommon and they certainly make it simpler for businesses to get work done, but she cautioned that allowing every user to install software anytime makes it easier for a hacker to do the same across multiple systems after compromising just a single machine inside the network.

“It sounds like [Verifone] found some malware in their network that must have come from an employee desktop because now they’re locking that down,” Litan said. “But the next step for these attackers is lateral movement within the victim’s network. And it’s not just within Verifone’s network at that point, it potentially expands to any connected partner network or through trusted zones.”

Litan said many companies choose to “whitelist” applications that they know and trust, but to block all others. She said the solutions can dramatically bring down the success rate of attacks, but that users tend to resist and dislike being restricted on their work devices.

“Most companies don’t put in whitelists because it’s hard to manage. But that’s hardly an excuse for not doing it. Whitelisting is very effective, it’s just a pain in the neck for users. You have to have a process and policies in place to support whitelisting, but it’s certainly doable. Yes, it’s been beaten in targeted attacks before — where criminals get inside and steal the code-signing keys, but it’s still probably the strongest endpoint security organizations can put in place.”

Verifone would not respond to questions about the duration of the breach in its corporate networks. But if, as sources say, this breach lasted more than six months, that’s an awful long time for an extremely skilled adversary to wander around inside your network undetected. Whether the intruders were able to progress from one segment of Verifone’s network to another would depend much on how segmented Verifone’s network is, as well as the robustness of security surrounding its various corporate divisions and many company acquisitions over the years.

The thieves who hacked Target Corp. in 2013, for example, were able to communicate with virtually all company cash registers and other systems within the company’s network because Target’s internal network resembled a single canoe instead of a massive ship with digital bulkheads throughout the vessel to stop a tiny breach in the hull from sinking the entire ship. Check out this story from Sept. 2015, which looked at the results of a confidential security test Target commissioned just days after the breach (spoiler alert, the testers were able to talk to every Target cash register in all 2,000 stores after remotely commandeering a deli scale at a single Target store).

The card associations often require companies that handle credit cards to undergo a third-party security audit, but only if there is evidence that customer card data was compromised. That evidence usually comes in the form of banks reporting a pattern of fraud on customer cards that were all used at a particular merchant during the same time frame. However, those reports come slowly — if at all — and often trickle up to the card brands weeks or months after stolen cards end up for sale in bulk on the cybercrime underground.

Corporate network compromises or the theft of proprietary source code (e.g. the same code that goes on merchant payment devices) generally do not trigger a mandatory third-party investigation by a security firm approved by the card brands, Litan said, although she noted that breaches which can be shown to have a material financial impact on the company need to be disclosed to investors and securities regulators.

“There’s no rule anywhere that says you have to disclose if your software’s source code is stolen, but there should be,” Litan said. “Typically, when a company has a breach of their corporate network you think it might hurt the company, but in a case when the company’s software is stolen and that software is used to transmit credit card data then everyone else is hurt.”

Sources told KrebsOnSecurity that Verifone commissioned an investigation of the breach from Foregenix Ltd., a digital forensics firm based in the United Kingdom that lists Verifone as a “strategic partner.” Foregenix declined to comment for this story.

LOW-HANGING FRUIT

Litan said if the attackers who broke into Verifone were indeed targeting payment systems in the filling station business, they were going after the lowest of the low-hanging fruit. The fuel station industry is chock-full of unattended, automated terminals that have special security dispensation from Visa and Mastercard: Fuel station owners have been given more time than almost any other industry to forestall costly security upgrades for new card terminals at gas pumps that are capable of reading more secure chip-enabled credit and debit cards.

The chip cards are an advancement mainly because they are far more difficult and costly for thieves to counterfeit or clone for use in face-to-face transactions — by far the most profitable form of credit card fraud (think gift cards and expensive gaming consoles that can easily be resold for cash).

After years of lagging behind the rest of the world — the United States is the last of the G20 nations to move to chip cards — most U.S. financial institutions are starting to issue chip-based cards to customers. However, many retailers and other card-accepting locations have been slow to accept chip based transactions even though they already have the hardware in place to accept chip cards (this piece attempts to explain the “why” behind that slowness).

In contrast, chip-card readers are still a rarity at fuel pumps in the United States, and Litan said they will continue to be for several years. In December 2016, the card associations announced they were giving fuel station owners until 2020 to migrate to chip-based readers.

Previously, fuel station owners that didn’t meet the October 2017 deadline to have chip-enabled readers at the pump would have been on the hook to absorb 100 percent of the costs of fraud associated with transactions in which the customer presented a chip-based card but was not asked or able to dip the chip. Now that they have another three years to get it done, thieves will continue to attack fuel station dispensers and other unattended terminals with skimmers and by attacking point-of-sale terminal hardware makers, integrators and resellers.

HOW WOULD YOUR EMPLOYER FARE?

My confidential source on this story said the closest public description of the email phishing schemes used by the Russian crime group behind both the MICROS and Verifone hacks comes in a report earlier this year from Trustwave, a security firm that often gets called in to investigate third-party data breaches. In that analysis, Trustwave describes an organized crime gang that routinely sets up phony companies and corresponding fake Web sites to make its targeted email phishing lures appear even more convincing.

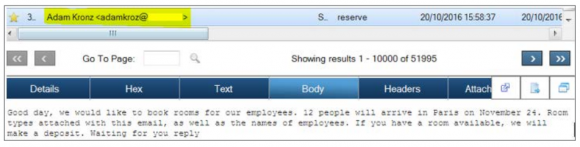

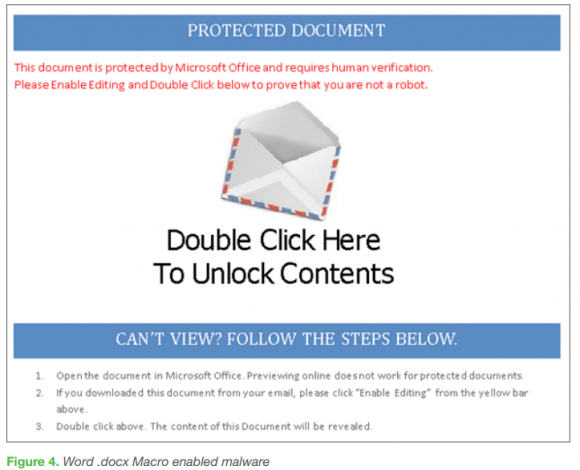

A phishing lure used in a malware campaign by the same group that allegedly broke into MICROS and Verifone. Source: Trustwave Grand Mars report.

The messages from this group usually include a Microsoft Office (Word or Excel) document that has been booby-trapped with malicious scripts known as “macros.” Microsoft disables macros by default in recent versions of Office, but poisoned document lures often come with entreaties that prompt recipients to override Microsoft’s warnings and enable them manually.

Trustwave’s report cites two examples of this social engineering; one in which an image file is used to obscure a warning sign (see below), and another in which the cleverly-crafted phishing email was accompanied by a phone call from the fraudsters to walk the recipient through the process of manually overriding the macro security warnings (and in effect to launch the malware on the local network).

According to Trustwave, this Russian hacking group prefers to target companies in the hospitality industry, and is thought to be connected to the breaches at a string of hotel chains, including the card breach at Hyatt that compromised customer credit and debit cards at some 250 hotels in roughly 50 countries throughout much of 2015.

In a common attack, the perpetrators would send a phishing email from a domain associated with a legitimate-looking but fake company that was inquiring about spending a great deal of money bringing many important guests to a specific property on a specific date. The emails are often sent to sales and event managers at these lodging facilities, with instructions for checking the attached (booby-trapped) document for specifics about guest and meeting room requirements.

This phishing lure prompts users to enable macros and then launch the malware by disguising it as a message file. Source: Trustwave.