Extortionists Wipe Thousands of Databases, Victims Who Pay Up Get Stiffed

Tens of thousands of personal and possibly proprietary databases that were left accessible to the public online have just been wiped from the Internet, replaced with ransom notes demanding payment for the return of the files. Adding insult to injury, it appears that virtually none of the victims who have paid the ransom have gotten their files back because multiple fraudsters are now wise to the extortion attempts and are competing to replace each other’s ransom notes.

At the eye of this developing data destruction maelstrom is an online database platform called MongoDB. Tens of thousands of organizations use MongoDB to store data, but it is easy to misconfigure and leave the database exposed online. If installed on a server with the default settings, for example, MongoDB allows anyone to browse the databases, download them, or even write over them and delete them.

Shodan, a specialized search engine designed to find things that probably won’t be picked up by Google, lists the number of open, remotely accessible MongDB databases available as of Jan. 10, 2017.

This blog has featured several stories over the years about companies accidentally publishing user data via incorrectly configured MongoDB databases. In March 2016, for example, KrebsOnSecurity broke the news that Verizon Enterprise Solutions managed to leak the contact information on some 1.5 million customers because of a publicly accessible MongoDB installation.

Point is, this is a known problem, and almost once a week some security researcher is Tweeting that he’s discovered another huge open MongoDB database. There are simple queries that anyone can run via search engines like Shodan that will point to all of the open MongoDB databases out there at any given time. For example, the latest query via Shodan (see image above) shows that there are more than 52,000 publicly accessible MongoDB databases on the Internet right now. The largest share of open MongoDB databases are here in the United States.

Normally, when one runs a query on Shodan to list all available MongoDB databases, what one gets in return is a list of variously-named databases, and many databases with default filenames like “local.”

But when researcher Victor Gevers ran that same query earlier this week, he noticed that far too many of the database listings returned by the query had names like “readme,” “readnow,” “encrypted” and “readplease.” Inside each of these databases is exactly one file: a database file that includes a contact email address and/or a bitcoin address and a payment demand.

Researcher Niall Merrigan, a solutions architect for French consulting giant Cap Gemini, has been working with Gevers to help victims on his personal time, and to help maintain a public document that’s live-chronicling the damage from the now widespread extortion attack. Merrigan said it seems clear that multiple actors are wise to the scam because if you wait a few minutes after running the Shodan query and then re-run the query, you’ll find the same Internet addresses that showed up in the database listings from the previous query, but you’ll also notice that many now have a different database title and a new ransom note.

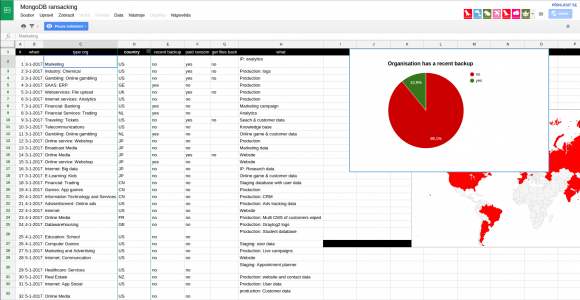

Merrigan and Gevers are maintaining a public Google Drive document (read-only) that is tracking the various victims and ransom demands. Merrigan said it appears that at least 29,000 MongoDB databases that were previously published online are now erased. Worse, hardly anyone who’s paid the ransom demands has yet received their files back.

A screen shot of the Google Drive document that Merrigan is maintaining to track the various ransom campaigns. This tab lists victims by industry. As we can see, many have paid the ransom but none have reported receiving their files back.

“It’s like the kidnappers keep delivering the ransom notes, but you don’t know who has the actual original data,” Merrigan said. “That’s why we’re tracking the notes, so that if we see the [databases] are being exfiltrated by the thieves, we can know the guys who should actually get paid if they want to get their data back.”

For now, Merrigan is advising victims not to pay the ransom. He encouraged those inclined to do so anyway to demand “proof of life” from the extortionists — i.e., request that they share one or two of the deleted files to prove that they can restore the entire cache.

Merrigan said the attackers appear to be following the plan of attack. Use Shodan to scan for open MongoDB databases, connect using anonymous access, and then list all available databases. The attacker may or may not download the data before deleting it, leaving in its place a single database file with the extortionists contact and payment info and ransom note.

Merrigan said it’s unclear what prompted this explosion in extortion attacks on MongoDB users, but he suspects someone developed a “method” for extorting others that was either shared, sold or leaked to other ne’er-do-wells, who then began competing to scam each other — leaving victims in the lurch.

“It’s like the early 1800s gold rush in the United States, everyone is just going west at the same time,” Merrigan said. “The problem is, everyone was sold the same map.”

Zach Wikholm, a research developer at New York City-based security firm Flashpoint said he’s confirmed that at least 20,000 databases have been deleted — possibly permanently.

“You’re looking at over 20,000 databases that have gone from being useful to being encrypted and held for ransom,” Wikholm said. “I’m not sure the Internet as a whole has ever experienced anything like this at one time. The fact that we can pull down the number of databases that have been compromised and are still compromised is not a good sign. It means that most victims are unaware what has happened, or they’re not sure how it’s happened or what to do about it.”

Normally, I don’t have great timing, but yesterday’s posts on Immutable Truths About Data Breaches seems almost prescient given this developing attack. Truth 1: “If you connect it to the Internet, someone will try to hack it.” Truth 2: “If what you put on the Internet has value, someone will invest time and effort to steal it.” Truth 3: “Organizations and individuals unwilling to spend a small fraction of what those assets are worth to secure them against cybercrooks can expect to eventually be relieved of said assets.”

H/T to Graham Cluley for a heads-up on this situation.

Update, 1:55 p.m. ET: Clarified the default settings of a MongoDB installation. Also clarified story to note that Gevers discovered the extortion attempts.